A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

The strangely named Rockstar Consortium has been in the news again, in part because some of its members just formed a new lobbying group, the Partnership for American Innovation, aimed at preventing the current political furor over patent trolls from bleeding into a general overhaul of the U.S. patent system. Yet Rockstar is perhaps the most aggressive patent troll out there today. Hence the mounting pressure in Washington, DC for the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division — which signed off on the initial formation of Rockstar two years ago — to open up a formal probe into the consortium’s patent assertion activities directed against rival tech firms, principally Google, Samsung and other Android device manufacturers.

Usually the fatal defect in antitrust claims of horizontal collusion is proving that competing firms acted in parallel fashion from mutual agreement rather than independent business judgment. In the case of Rockstar — a joint venture among nearly all smartphone platform providers except Google — that problem is not present because the entity itself exists only by agreement among its owner firms. The question for U.S. antitrust enforcers is thus the traditional substantive inquiry, under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, whether Rockstar’s conduct is unreasonably restrictive of competition.

Despite its cocky moniker, Rockstar is simply a corporate patent troll hatched by Google’s rivals, who collectively spent $4.5 billion ($2.5 billion from Apple alone) in 2012 to buy a trove of wireless-related patents out of bankruptcy from Nortel, the long-defunct Canadian telecom company. It is engaged in a zero-sum game of gotcha against the Android ecosystem. As Brian Kahin explained presciently on DisCo then, Rockstar is not about making money, it’s about raising costs for rivals — making strategic use of the patent system’s problems for competitive advantage. Creating or collaborating with trolls is a new game known as privateering, which allows big producing companies to do indirectly what they cannot do directly for fear of exposure to expensive counterclaims. Essentially, it’s patent trolling gone corporate. As another pro-patent lobbying group said at the time, Rockstar represents “a perfect example of a ‘patent troll’ — they bought the patents they did not invent and do not practice; and they bought it for litigation.” Predictiv’s Jonathan Low put it quite well in his The Lowdown blog:

The Rockstar consortium, perhaps more appropriately titled “crawled out from under a rock,” is using classic patent troll tactics since their own technologies and marketing strategies have fallen short in the face of the Android emergence as a global power. Those tactics are to buy patents in hopes of finding cause, however flimsy, to charge others for alleged violations of patents bought for this purpose. Rockstar calls this “privateering” in order to distance itself from the stench of patent trolling, but there are no discernible differences.

Continue reading Rockstar’s Patent Trolling Conspiracy

Google’s competitors “are locked in hand-to-hand combat with Google around the world and have the mistaken belief that criticizing us will influence the outcome in other jurisdictions.”

The coalition of companies that for years has unsuccessfully been pressing antitrust complaints against Google for search “abuse” — FairSearch.org — insists Google must be restrained for fear the Mountain View company will steer search users to its commercial products, like flight bookings. The group’s most recent publicity event, held at the ABA’s Antitrust Section annual spring meeting last week, repeated those same claims. FairSearch ventured as well into new ground, attacking what it terms Google’s unreasonably restrictive Android licensing practices.

There are four straightforward reasons FairSearch is wrong.

1. Predictions of Foreclosure Have Proven Totally Baseless.

When Google purchased travel software maker ITA in 2011, FairSearch maintained that Google would exploit its control over the ITA tools that power other online travel agencies, along with many of the airlines’ own sites, to usher competing search services off the stage, then jack up ad rates for travel queries and favor flights from particular airlines.  Three years later, nothing like that has happened. In fact, Google Flight Search is not among the top 100 or even the top 200 travel listing sites. Rather, it’s in 244th place, behind Hipmunk, with just .04% of travel queries. Real-world experience, in other words, reveals that the predicted competitive risks on which FairSearch bases its advocacy are both hypothetical and fanciful. Continue reading Four Reasons Fairsearch Is Wrong Three years later, nothing like that has happened. In fact, Google Flight Search is not among the top 100 or even the top 200 travel listing sites. Rather, it’s in 244th place, behind Hipmunk, with just .04% of travel queries. Real-world experience, in other words, reveals that the predicted competitive risks on which FairSearch bases its advocacy are both hypothetical and fanciful. Continue reading Four Reasons Fairsearch Is Wrong

The week before last I participated in a conference on mobile payment technologies. I expected to find out more about Square and other startups that have begun to revolutionize credit card acceptance by solo businesses like food trucks. What I learned instead is that this nascent industry is way bigger than the emerging near-field communications (NFC) protocol Apple unexpectedly did not include in its new iPhone 5. More surprisingly, it seems the biggest attraction for inventors and investors isn’t the payment transactions themselves at all.

Some take-aways:

- A bunch of different technologies are competing at the standards/platform level for mobile payment processing. These include EMV, Isis and TSM, as well as NFC. A major driver in adoption is that new ventures are cutting deals with point-of-sale (POS) equipment vendors to integrate their protocols into the next software updates for these ubiquitous checkout devices. The biggest barrier to adoption is security and PCI compliance.

- Many of the largest U.S. retailers (7-Eleven, Walmart, Sears, Best Buy, etc.) have teamed up in a joint venture called MCX, which has yet to decide on a common approach to use of smartphones as payment devices. By virtue of their ubiquity, the MCX players may have the scale to make their selection of mobile payment technology an inflection point in this transformation.

- The advantage of mobile payments to retailers is not simply allowing consumers a convenient way to make purchases. Rather, it is the Holy Grail of demographic, time and location information allowing Location Based Marketing (LBM) in the “last three feet.” By capturing GPS-enabled location data, using wireless geofencing to engage in push/pull marketing interactions — think shopkick and the like (disclaimer: shopkick has been a client of mine) — and mining that data, mobile payment companies will know more about consumer preferences and behavior than SKU-level retailers or the major credit card processors like Visa and MasterCard.

This presents some interesting questions from a business and social perspective. Will and should the same liability approach used for traditional credit cards, quite protective of the consumer, apply where the credit card is essentially integrated into a smartphone? How will mobile POS (MPOS) technologies change the retail experience, for instance use of swipeable tablets by sales clerks for “line-busting” at peak sales hours?  Will consumers be more comfortable with non-persistent technologies that utilize one-off QR codes for payment authentication than the always on NFC payment “wallet” backed by Google? Given the shambles of our national financial regulatory system in the U.S. post-2008, which of the slew of federal agencies, from the Federal Reserve to the much-maligned CFPB, will have jurisdiction to regulate this new market, and what sort of regulation is appropriate? Will consumers be more comfortable with non-persistent technologies that utilize one-off QR codes for payment authentication than the always on NFC payment “wallet” backed by Google? Given the shambles of our national financial regulatory system in the U.S. post-2008, which of the slew of federal agencies, from the Federal Reserve to the much-maligned CFPB, will have jurisdiction to regulate this new market, and what sort of regulation is appropriate?

Several months ago I asked, only partially in jest, whether technology had finally made currency irrelevant. Mobile payment technologies are only in their infancy in America, which lags well behind Japan and the EU. But in light of the scale of the U.S. economy, what the markets do here can have a profound effect on financial practices worldwide. The problem is that because the American approach to data privacy and ownership — where the manufacturer or merchant owns the transactional records — is so different, the driver of MPOS innovation here may not translate well abroad. Jerry Maguire’s catch phrase must be refined a bit, because mobile payment innovation in the U.S. wants to be shown the data, not the money.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

The battle to beat Google’s Android mobile phone OS is quickly turning into a legal bonanza. Apple is suing HTC, Samsung and Motorola, all makers of wireless phones with the Android platform. Oracle is seeking up to $6.1 billion in a patent lawsuit against Google, alleging Android infringes Oracle’s Java patents. And Microsoft is suing Motorola over its Android line.

That’s all perfectly fine from an antitrust and competition standpoint — leaving aside the harder policy question of whether using patent infringement litigation to block competition should be permissible. Enforcing property rights is a legitimate and rational business activity that, absent “sham” lawsuits, is not second-guessed by antitrust enforcement agencies or courts. There can be exclusionary consequences, but they are a result of the patent laws in the first instance, not of themselves anything anticompetitive by the patent holder.

A much more troubling aspect of the increasing IP (or “IPR” as they say across the pond) battles surrounding Android is the recent sale of Nortel’s 6,000 or so wireless patents at a bankruptcy auction in Canada to a collection of bidders including Apple, Microsoft, RIM, EMC, Ericsson and Sony. How Apple Led The High-Stakes Patent Poker Win Against Google, Sealing Ballmer’s Promise | TechCrunch. The winning consortium bid more than $4.5 billion — some five times Google’s opening bid and, according to some pundits, far more than the portfolio was worth — to gain control of the patents.

“Why is the portfolio worth five times more to this group collectively than it is to Google?” said Robert Skitol, an antitrust lawyer at the Drinker Biddle firm. “Why are three horizontal competitors being allowed to collaborate and cooperate and join hands together in this, rather than competing against each other?”

Antitrust Officials Probing Sale of Patents to Google’s Rivals | Washington Post.

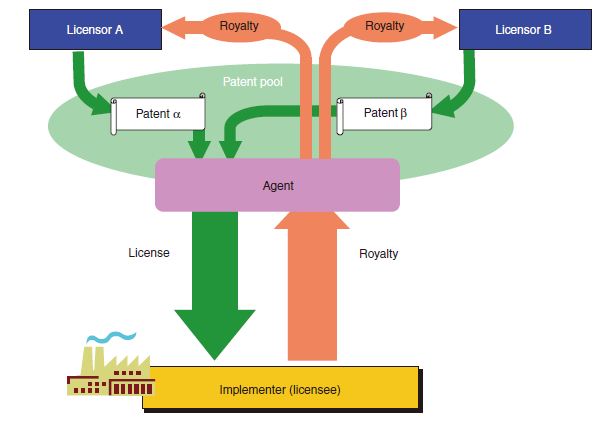

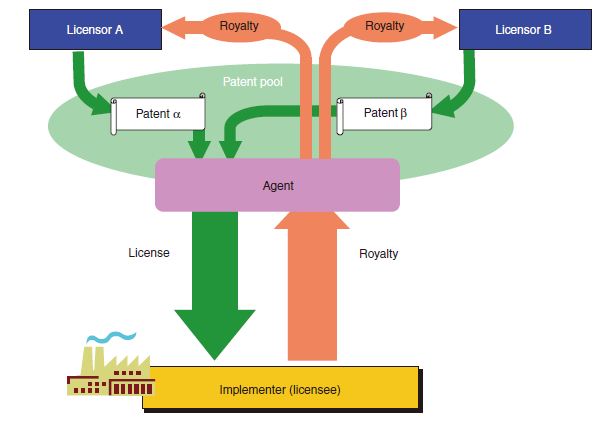

These are good questions. Patent “pools,” which are collections of horizontal competitors sharing patent licenses among themselves, are today generally considered procompetitive under the antitrust laws where they (a) are limited to technologically essential or “blocking” patents, and (b) do not contain ancillary restraints, such as resale price-setting or restrictions on participant use of alternative technologies. (MPEG, WiFi, LTE and other communications technologies are prime examples of patent pools.) The theory is that, with price effects eliminated, the cross-licensing of patents that might otherwise be used to block entry into a market reduces barriers to entry and increases efficiency.

Yet the consortium which won the Nortel wireless portfolio, revealing dubbed “Rockstar Bidco,” includes nearly everyone in the mobile phone and wireless OS businesses except Google. If these players agreed among themselves not to license their own patents to Google, that would be a per se illegal group boycott (also known as a concerted horizontal refusal to deal). Competitors cannot allocate markets or conspire to keep a rival out of the marketplace. It is unclear whether Google was invited to join Rockstar Bidco, but unless Larry, Sergey and Eric turned down such an offer, it seems a fair case can be made that the consortium bid was in effect an implicit horizontal agreement not to include Google. Post-auction, the reality of licenses will clearly tell us whether the joint ownership structure was a pretext to cover a refusal to deal. No one knows what the consortium intends to do with the Nortel patent portfolio; they won’t say. Microsoft, RIM And Partners Mum On Plans For Nortel Patents | Forbes. Yet the consortium which won the Nortel wireless portfolio, revealing dubbed “Rockstar Bidco,” includes nearly everyone in the mobile phone and wireless OS businesses except Google. If these players agreed among themselves not to license their own patents to Google, that would be a per se illegal group boycott (also known as a concerted horizontal refusal to deal). Competitors cannot allocate markets or conspire to keep a rival out of the marketplace. It is unclear whether Google was invited to join Rockstar Bidco, but unless Larry, Sergey and Eric turned down such an offer, it seems a fair case can be made that the consortium bid was in effect an implicit horizontal agreement not to include Google. Post-auction, the reality of licenses will clearly tell us whether the joint ownership structure was a pretext to cover a refusal to deal. No one knows what the consortium intends to do with the Nortel patent portfolio; they won’t say. Microsoft, RIM And Partners Mum On Plans For Nortel Patents | Forbes.

This author happens not to be a fan of Android; I’m a very happy iPhone user since day one of the Apple wireless revolution. This does not mean, though, that I can agree with a business strategy in which all of the other players in the mobile phone industry gang up on Google. (It is unclear were Nokia fits into all of this, but given the steadily decreasing share for its Symbian OS, I suspect the inclusion or not of Nokia will not be dispositive.)

The antitrust issue this presents is a thorny one, which frequently comes up in connection with trade associations and technical standards. When competitors collaborate, is under-inclusiveness or over-inclusiveness worse? Which is the bigger threat to competition? That is, if a trade group opens a collective buying consortium, for instance, is it better from an antitrust perspective to require that it be open to all — so that some rivals are not deprived of the scale economies — or that the consortium includes less than all firms in the market — so that competition in purchasing will drive down input prices?

Another concern is that, by excluding Google, the Rockstar consortium allows the other competitors to utilize the patents without paying license fees (since they now own them), leaving Google alone to need licenses for its Android OS. Does Nortel Patent Sale Make Google An Antitrust Victim? | TechFlash. That is a variant of “raising rivals’ costs” (here one rival only), which has over the past three decades become a recognized basis for assessing the anticompetitive nature of unilateral, single-firm conduct. When a group includes horizontal competitors who collectively control a huge share of the market, raising rivals’ costs supplies the anticompetitive “purpose or effect” needed to make out a rule of reason antitrust claim, even if the group boycott concern is misplaced or ameliorated. Here the intent to slow down Android is clear; whether that is anticompetitive, exclusionary or not is more ambiguous. Apple, Microsoft Patent Consortium Trying to Kill Android | eWeek.com.

There are precious few judicial decisions in this area and the IP licensing guidelines from DOJ/FTC do not really speak to the question. For that reason alone, the Rockstar Bidco venture, in my view, merits a very close look by the U.S. competition agencies. Allowing Google’s mobile phone competitors to do indirectly, with joint patent ownership, what they could not do indirectly, by agreeing not to license to Google, would be an incongruous result. On the other hand, a remedy may be worse than the harm. In standards, for example, it is often the case that antitrust risks are mitigated by requiring the holder of an essential patent to agree to so-called FRAND licensing (fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms and conditions). That’s an appropriate remedy where under-inclusiveness is the problem, so long as there’s a market measure for a “fair” license (royalty) price. Where the licensor, as in this instance, is everyone except the licensee, I for one fear there would be no objective way to assess whether license rates were reasonable.

DOJ's Christine Varney The lack of an effective remedy for a competition problem does not, of course, require that the transaction involved be blocked. At the same time, where a problem cannot be fixed, that is a good enforcement policy reason not to allow the structural market conditions giving rise to the issue in the first place. Put another way — a slight modification of an old aphorism — if there’s no remedy, maybe there should be no right. Whether the viability of the Rockstar consortium is decided by outgoing Assistant Attorney General Christine Varney or her September successor, the forthcoming answer should be interesting.

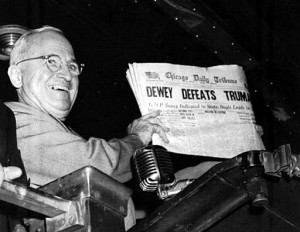

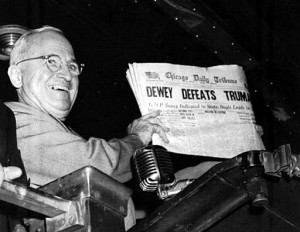

60 years ago, when Harry Truman beat Tom Dewey for the presidency, it was widely predicted by pollsters that Truman would lose. This led to the famous “Dewey Beats Truman” headline in the newspaper proudy flashed by the winning candidate.

The problem, it was later revealed, was that the Gallup organization based its poll results on responses to telephone inquiries. But in the late 1940s, that selection inevitably favored wealthier Republicans, leading to skewed poll results.

Gallup is best known for that one half-century-old blunder. There’s a terrible irony in that. The studious George Gallup did more than anyone to put opinion polling on solid ground.

We have a similar problem today, it appears to me. While telephone subscribership has now become ubiquitous, increasingly many citizens — especially twenty-somethings — no longer use landline telephones, instead going completely wireless. The proportion was 1 in 6 three years ago and continues to increase steadily. Pollsters, however, still base their surveys on landline phone subscribers. In fact, under FCC regulations it is unlawful to telephone a wireless subscriber for a “solicitation” or using an autodialer (a technical prerequisite to modern polling) without either their consent or a prior business relationship. Therefore, despite a non-profit exemption in the FCC’s rules (which, unlike the Federal Trade Commission’s “telemarketing sales rule,” do not expressly exempt political polling), the law is standing in the way of accurate political predictions.

How this will play out in next Tuesday’s elections is unclear to me, as I claim no special expertise in political punditry. But it is revealing that the problems experienced in 1948 are recurring today in a different form due to technological change and the accelerating proliferation of wireless communications devices.

Several of the previous posts in my The Law of Social Media essay series focus on core legal issues, such as copyright in user-generated content and employer use of social media for HR decisions. This one is a bit different. Like John Naisbitt, it describes what I am convinced are the most significant law/policy “megatrends” affecting the social media space today.

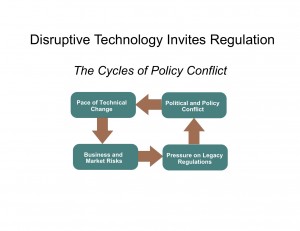

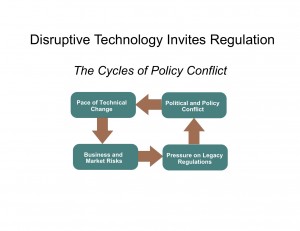

As an overview, consider the following scenario—and click for a larger image:

As the graphic indicates, the reality is that disruptive technologies quickly and visibly invite governmental regulation. That’s because change creates business and policy risks, which threaten legacy products and powerful business incumbents, and in turn which cause political pressures to protect established constituencies. Since social media is most assuredly a disruptive force, this circular pattern will likely manifest itself — in fact, as I discuss below it already has — in public policies towards social media and social networking communications.

1. Censorship & Filtering

Governments absolutely hate “unfiltered” social media and will move to censor and control it.

In the East, the basis for such censorship is political and religious oppression, as in Iran, North Korea, China, etc. In the West, the more unlikely culprit has been intellectual property (e.g., music and movie copyrights) and obscenity, as in Australia, France and New Zealand’s efforts to install country-wide porn filters and institute a “the strikes” rule against P2P file sharing. And everywhere, government mourns the loss of the historic financial and advertising basis for traditional media like newspapers and broadcast television, proposing to bail out or subsidize the latter in order to prevent social media from achieving dominance at the expense of last century’s communications technologies. Censorship is far from dead on the Web; in fact, it’s really only beginning.

2. Privacy

The EU’s strict data protection (privacy) regime will spread and overtake the US opt-out approach.

Most everyone knows that the European Union has a highly protective scheme of individual privacy in the digital age. Fewer understand that in the United States, with the exception of specially regulated industries like health care and financial services, the only privacy protections available are basically those the Constitution provides as against the government. That will change, however. The EU is too large a market for businesses to overlook, commerce today is fully globalized and while the United States remains the least privacy-centric of any major industrialized nation, that is changing as legislators and regulators more often choose an opt-in requirement for newer, albeit still infrequent, electronic privacy measures.

3. Criminal Law

Cyber offenses will (finally) be created.

In the past, criminal violations involving the Internet and online activities have largely focused on corporate interests, like the Anti-Cybersquatting, CFAA and CAN-SPAM Acts. But the current proliferation of pedophilia, cyber-bullling, stalking and other socially offensive digital-centric conduct is different. Many times, existing criminal laws — for instance, of assault — are not broad enough to cover online conduct. Other time, prosecutors are reluctant to indict and juries even more reluctant to convict. Yet the US congressional approach to indecency on the Web has for more than a decade been to attempt to ban conduct deemed seedy, whether pornography or gambling, to avoid having the “new” media infected with perceived old evils, for instance the Communications Decency Act of 1996. As a result, there is a good chance, well above 50% in my estimation, that the next several years will bring a proliferation of state and federal laws making criminally unlawful specific forms of online activity deemed socially deviant or harmful.

4. Anonymity

Anonymity on the Internet is under assault and may be lost.

A timely prediction, given that just yesterday two different courts compelled the unmasking of anonymous commenters in civil pretrial discovery—when the posters were not even parties to the cases. Ninth Circuit Upholds Unmasking of Online Anonymous Speakers and Illinois Appellate Court Unmasks Anonymous Commenters. There are a variety of reasons, but the principal one is that by defeating anonymity, politicians can be seen as “protecting” the victims of Web-based schemes, involving both antisocial (i.e., bullying, extortion, etc.) and anti-consumer (i.e., stock pump-and-dump chats, etc.) behavior, which sometimes end quite tragically, as in teenage suicides. This is reinforced by the continuing efforts of copyright holders (music, photos, video, news) to require ISPs to disgorge the identities of infringing users and by the FTC’s sponsored blogging “guidelines,” which support the theme of transparency from a consumer protection perspective. Almost alone among nations, only America has a Tom Paine and Federalist Papers/Primary Colors tradition of anonymous or pseudonymic political speech, yet even here — unless the Supreme Court intervenes — short-term passions, politics and national security phobias almost always trump free speech. The old proverb was that “No one knows if you are a dog on the Internet.” Don’t plan on barking much longer!

5. Competition

Competition and antitrust laws will reshape social media providers.

My core training is in antitrust law, although this megatrend has little to do with yours truly. Instead, it stems from the reality that Facebook, Apple and Google, among others, are already facing competition law investigations in the advertising, mobility, search and handset markets. From an economic perspective, there are very strong, positive network effects in social media, far greater than were true in the 1990s for Microsoft’s WIndows OS. As a consequence, viral expansion leads to small social media companies getting VERY big VERY fast: witness Facebook’s 500 million users and Twitter’s phenomenal hockey-stick growth curve. It is difficult for entrepreneurs to shake the old underdog mentality even when their companies become big enough that market power makes their business practices and acquisitions suspect, as Mark Zuckerberg is now learning to his chagrin. And when fueled by financial underwriting from legacy competitors — the dark political underbelly of Washington, DC and Brussels, Belgium antitrust battles — the “nascent” stucture of social media and wireless markets has, to date, not proven sufficient to keep the mitts of antitrusters from the US Department of Justice and the EU’s Competition Directorate from meddling—e.g., Google/Yahoo (2008-09) and Oracle/Sun (2009-10), to name a couple of examples.

6. Location

Location-bsed services will spawn a host of new policy battles.

“Location, location, locations” is not just a real estate slogan, it’s the cross-hairs for a number of policy trends affecting social media. The indicia are not found not just in the geometrically increasing popularity of geo-tagged photos, location check-in apps and games, and the like, but as well and perhaps more importantly in the fact that as wireless communications and data come to dominate telecom — a direct consequence of social networking — regulatory oversight follows almost automatically. “Nomadic” services like VoIP and video chart (e.g., FaceTime), in contrast, present an equally great threat to the established order by making location a matter of indifference. At bottom, this is an industry where eyeballs and advertising dollars still rule. So as marketers devise ever-clever ways to monetize users’ location (including the launch this week of my client shopkick’s location marketing app) all of the bad stuff that can happen online is bound, eventually, to arise with respect to location-based services. LBS isn’t bad; some people are bad. Unfortunately for the FourSquares and Gowallas of the social media world, that has never been enough in most societies to stop gun control—and it won’t be enough to arrest the coming push for consumer protection and marketing regulation in the location services space.

Note: I first used the “megatrends” metaphor while presenting at the 140 Characters Conference-DC (#140onf-dc) in June 2010, and am indebted to organizer Jeff Pulver for serving as my muse for these thoughts. Thanks, Jeff!

I’m not sure I am altogether comfortable with this technology, yet.

Posted via web from glenn’s posterous

Earlier this week, one month after originally scheduled and following a year of study based on more than 30 requests for public comment — generating some 23,000 comments totaling about 74,000 pages from more than 700 parties — the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) released a 360-page report to Congress on broadband Internet access services. The National Broadband Plan (NBP) encompasses more than 200 recommendations for how Congress, other government agencies and the FCC can improve broadband availability, adoption and utilization, especially for meeting such “national purposes” as economic opportunity, education, energy and the environment, healthcare, government performance, civic engagement and public safety.

Titled Connecting America and praised on its publication by President Obama,1 the NBP presents a wide range of legal, policy, financial and technical proposals, all devoted to meeting the legislative order—first articulated in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA)—of recommending ways to make broadband ubiquitous for Americans. Much of the general outlines and major recommendations of the plan were revealed in a series of public appearances and media briefings by FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski over the past several weeks. Only the NBP’s executive summary was made available before the full plan’s official March 16 publication. The public release of the entire document reveals the whole plan, including details on the recommendations as well as the reasoning behind them and the FCC’s goals.

The ambitious NBP sets as a national goal the delivery to all Americans of 100 megabits per second (Mbps) Internet service within 10 years, informally known as the “10 squared” objective. Its premise is that “[l]ike electricity a century ago, broadband is a foundation for economic growth, job creation, global competitiveness and a better way of life.”2 The policies and actions recommended in the plan fall into three major categories: fostering innovation and competition in networks, devices and applications; redirecting assets that government controls or influences in order to spur investment and “inclusion”; and optimizing the use of broadband to help achieve national priorities.

The FCC’s plan addresses wide range of interrelated issues, such as intercarrier compensation, universal service reform, spectrum reallocation (making 500 megahertz of spectrum newly available for broadband within 10 years), digital literacy, E-Rate (Schools and Libraries Program of the Universal Service Fund) services, set-top-box unbundling, affordability, “smart grid” electrical services, telemedicine, state and municipal broadband networks, distance education, wireless data services, homeland security and first-responder communications, wireless connectivity to digital-learning devices, Internet anonymity and privacy, data-center energy efficiency, video “gateway” network interface devices, and use of unlicensed spectrum (such as WiFi). The plan includes a proposal for the federal government to repurpose $15.5 billion in existing telecom-industry subsidies away from traditional landline telephone services to broadband, concluding that—

If Congress wishes to accelerate the deployment of broadband to unserved areas and otherwise smooth the transition of the [Universal Service] Fund, it could make available public funds of a few billion dollars per year over two to three years.3

Release of the NBP marks the start of what is likely to be a long and hotly debated implementation process, as the plan pits the interests of different industry segments against one other and tests the limits of the FCC’s regulatory authority.4 While lauding the plan’s aspirations, some critics in the first days after its release include broadcast television stations that are being asked to “voluntarily” relinquish valuable digital spectrum, satellite and cable companies that object to further regulation of their so-called navigation devices and rural telephone providers that are concerned with the potential loss of substantial Universal Service Fund (USF) revenues. Information technology (IT) and content delivery networks (CDNs) also have expressed concern that the FCC’s related net neutrality initiative would circumscribe their ability to offer quality of service (QoS) and packet-prioritized media services. Free-market advocates (both think tank and government) as well as Republican FCC Commissioner Robert McDowell have already declared that the plan is unnecessary or at least unnecessarily regulatory.5

Connecting America details a series of economic and public policy goals for the United States, which according to some studies has fallen in penetration and “adoption” of broadband Internet services from first in the world in the late 1990s to somewhere between 15th place to 20th place as of 2008.6 These goals are highlighted below.

- At least 100 million U.S. homes should have affordable access to actual download speeds of at least 100 Mbps and actual upload speeds of at least 50 Mbps.

- The United States should lead the world in mobile innovation, with the fastest and most extensive wireless networks of any nation.

- All Americans should have affordable access to robust broadband service, and the means and skills to subscribe if they so choose.

- Every American community should have affordable access to at least 1 gigabit per second broadband service to anchor institutions, such as schools, hospitals and government buildings.

- To ensure the safety of the American people, every first-responder should have access to a nationwide, wireless, interoperable broadband public-safety network.

- To ensure that America leads in the clean-energy economy, all Americans should be able to use broadband to track and manage their real-time energy consumption.

All of these goals are supported by proposals for the federal government to become more deeply involved in collecting and assessing statistical metrics on the availability, speed and use of broadband services and that the FCC impose “performance disclosure requirements” and “performance standards” on broadband service providers, including wireless and cellular carriers.7 As the trade publication Telecommunications Reports notes:

This recommendation illustrates how the plan could bump up against independent congressional initiatives. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D.-Minn.) introduced a broadband performance management bill along similar lines that directed an FCC rulemaking action, rather than NIST standards, and which mandated industry use of the terms as the FCC defines them.8

In some of its more controversial recommendations, the NBP proposes that broadband success be measured not only by the statutory objective of “access to broadband capability,”9 but also by adoption percentages and affordability, using a national commitment to “inclusiveness” as the principal justification. “While it is important to respect the choices of those who prefer not to be connected, the different levels of adoption across demographic groups suggest that other factors influence the decision not to adopt. Hardware and service are too expensive for some. Others lack the skills to use broadband.”10 The FCC also proposes creation of a Digital Literacy Corps, modeled after President John F. Kennedy’s Peace Corps initiative, to educate minority and disadvantaged citizens on the use and importance of computers and Internet services. Having successfully subsidized the connection of more than 95 percent of America’s classrooms to the Internet, the FCC’s plan further recommends that the E-Rate program be expanded to cover off-campus network use, e-readers and a variety of even newer functions. Among the recommendations for congressional action, the highest price tag—up to $16 billion—would be for grants to cover capital and operational costs of an interoperable public-safety mobile broadband network. As was revealed previously, the NBP also proposes auctioning the 700-megahertz “D block” rather than allocating it to public safety and first-responder services.

There are likely to be numerous FCC notice-and-comment rulemakings, legislative hearings and policy workshops initiated over the next 12 to 18 months to implement the NBP. As Connecting America emphasizes in its executive summary:

Public comment on the plan does not end here. The record will guide the path forward through the rulemaking process at the FCC, in Congress and across the Executive Branch, as all consider how best to implement the plan’s recommendations. The public will continue to have opportunities to provide further input all along this path.

The FCC has stated it will publish a timetable of actions in the near future and is anticipated to begin what may be considered more challenging NPRM proceedings, such as USF reform, within 60 to 90 days. Whether in the IT, telecom, energy or healthcare industries, companies involved in a wide range of different markets are likely to be affected by the National Broadband Plan for years to come and should consider participating in the rulemaking and parallel legislative processes.

**[This is a client alert I prepared for my law firm, Duane Morris LLP, which holds the copyright. The alert is available here.]

Footnotes

- “President Obama Hails Broadband Plan,” Washington Post, March 16, 2010.

- Connecting America at xiv, 9.

- Connecting America at xiii.

- See, e.g., “FCC Chairman Genachowski Confident in Authority over Broadband, Despite Critics,” Washington Post, March 3, 2010.

- “FCC’s National Broadband Plan Raises Divisive Issues,” USA Today, March 17, 2010. Compare B. Reed, “Who Else Wants National Broadband?”, Business Week, March 16, 2010, with J. Chambers, “Why America Needs a National Broadband Plan,” Business Week, March 16, 2010.

- Connecting America at xiv.

- Connecting America at 35–36. “The FCC and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) should collect more detailed and accurate data on actual availability, penetration, prices, churn and bundles offered by broadband service providers to consumers and businesses, and should publish analyses of these data.” Id. at 35.

- T.R. Daily, March 15, 2010, at 2.

- ARRA § 6001(k)(2)(D), 123 Stat. 115, 516 (2009).

- Connecting America at 23.

Yes, it is manifestly true that, led by the iPhone, of course, wireless Internet-enabled devices are chewing up bandwidth on 3G and other cellular networks at an unprecedented rate. But is that really a crisis? FCC Chairman Warns of “Looming Spectrum Crisis” for Wireless Devices.

I’ve got a lot of respect for Julius Genachowski. But on this point, I suggest he is all wet. Look at the historical parallels. Thomas Malthus warned more than 200 years ago of a food crisis as the industrial revolution expanded populations, and that did not happen either. In wireless data, the technology has advanced by an order of magnitude in just the past 3-4 years, like fiber optics using WDM to cram more capacity into the same amount of bandwidth. What is 3g today is almost 4G in Japan and other nations.

So don’t bet against technology. Increased efficiency in wireless data protocols — OFDM, for instance — trumps spectrum capacity all the time.

Posted via email from glenn’s posterous

Yesterday the U.S. House of Representatives voted to restrict TSA from conducting what have become known as “virtual strip-searches.” House Restricts “Strip-Search Machines” [WashingtonWatch.com]. The bill provides, among other things, that:

Whole-body imaging technology may not be used as the sole or primary method of screening a passenger under this section. Whole-body imaging technology may not be used to screen a passenger under this section unless another method of screening, such as metal detection, demonstrates cause for preventing such passenger from boarding an aircraft.

Although promoted as less intrusive than x-rays, explosive sniffers and the like, this new technology presents a significant threat to personal privacy. As the sponsor (Rep. Jason Chaffetz, R-Utah) said, “Nobody needs to see my wife and kids naked to secure an airplane.” My colleague Chris Calabrese of the ACLU makes it graphically clear:

these machines produce strikingly graphic images of passengers’ bodies when they are utilized as part of the airport screening process. Those images reveal not just graphic images of “naughty parts,” but also intimate medical details like colostomy bags.

"Privacy Screen" Filter Privacy advocacy groups are, for obvious reasons, alarmed. It is very much like the “Tunnel of Truth” hypothesized in the 1990 sci-fi film Total Recall. That was scary indeed! Not unsurprisingly, on May 31, a coalition of advocacy groups including the ACLU, the Electronic Privacy Information Center, Gun Owners of America, and the Consumer Federation of America sent a letter to Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano asking her to “suspend the program until the privacy and security risks are fully evaluated.”

That will never happen. It its zeal to “protect” Americans traveling by air, TSA has turned the check-in experience into the U.S. equivalent of the Star Chamber, where ordinary citizens are presumed to be dangerous just by, for instance, wearing shoes — now routinely x-rayed separately at every U.S. airport — or putting liquids into carry-on luggage. The millimeter wave and related strip-search technologies ratchet this up yet another level. Use of a “privacy screen” to cover intimate areas is hardly an answer.

Tunnel of Truth (1990)

In my view, TSA is out of control. Yes, there were security lapses leading to 9/11, but they did not arise from business or vacation travelers and, with a bit more diligence (like following up on middle eastern males taking flying lessons but rejecting landing practice) the government could target those likeliest to have real terrorist connections. Just as TSA’s “no fly list” was overreaching, so is virtual body searching. We do not need this and we do not need TSA. I say abolish the agency, something with which Jim Harper of the Cato Institute, the premiere libertarian think tank, agrees.

|

|

Three years later,

Three years later,