A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

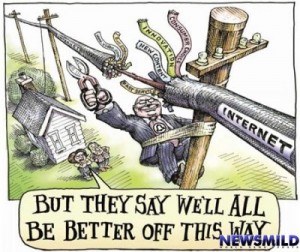

The news today is all about Tuesday’s “open meeting” at the FCC, where at long last a proposed regime for network neutrality will formally be considered. “There are of course a lot of moving pieces surrounding this debate, and however the chips fall, it’s going to have a long-term affect over how the Internet operates over the next several years.” The FCC Votes on Net Neutrality Tomorrow; The Internet Waits | AllThingsD.

Actually, the modest few rules FCC Chairman Genachowski has proposed are so trivial that, like all good policy, compromises or settlements, they have angered both the left and the right. The former deplores the scheme as worse than nothing, while the latter says it is a slippery slope to full regulation of the Internet.

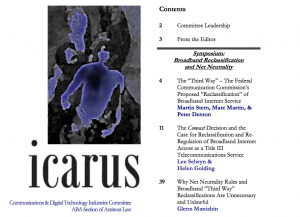

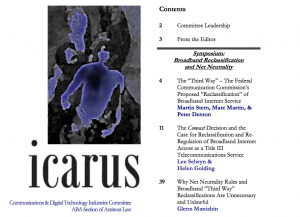

The far more important issue tomorrow is the legal framework under which the FCC will propose net neutrality rules. After the Comcast decision in April of this year — in which a federal court of appeals threw out the Commission’s decision to sanction undisclosed throttling of P2P traffic by ISPs — net neutrality has been in a state of extreme jurisdictional chaos. For an overview, read the Fall 2010 edition of the ABA’s Icarus magazine, a symposium issue on so-called “Title II reclassification” featuring, among others, this author.

About a month ago, Genachowski also announced has was abandoning his Third Way reclassification approach. That’s a brilliant decision, as reclassification was doomed to judicial reversal and, almost certainly, an injunction or stay against implementation. The alternative is for the FCC to articulate the ancillary jurisdiction linkage or nexus between the agency’s specific areas of delegated responsibility — telephony (Title II) and broadcasting (Title III) — and its general authority over “communications by wire or radio.” Yet to do that the agency needs to distance itself from the protectionist roots and core of the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, which for 40+ years has been used principally to squelch or constrain new technologies in order to prevent market competition with older, established industries (constituencies).

Here’s what I wrote earlier:

Ancillary jurisdiction under Southwestern Cable represents the low-water mark of communications jurisprudence. It was fashioned as a legal matter to permit FCC control of CATV, the infant predecessor to today’s robust cable programming industry, as a means of protecting the Commission’s power to regulate broadcast television. . . . It was protectionism to the core [and] epitomizes the conservative critique of administrative agencies as regulatory capture.

There is no longer an appetite in Congress to utilize governmental regulation to protect incumbents and vested commercial interests against competition and new entry. Hence, because it lacked and still lacks the political will to justify net neutrality on the ground of protecting its Title II and III jurisdiction over telephony and broadcasting — by sheltering the legacy providers of those services against disintermediation — the agency can never provide the requisite “nexus” demanded by the Comcast opinion.

Since no current policy or political figure today can admit to using regulation to handicap new entrants and favor established business interests, ancillary jurisdiction will remain the dark, dirty secret of administrative law until it is moved to a new footing. Imagine if the FCC reasoned that with IP convergence, services that formerly were within its Communications Act authority, like telephony and television, are increasingly moving to an Internet-based delivery system that, if it continues, will eventually leave all of communications beyond the FCC’s jurisdiction. Under this approach, the Commission could demonstrate a clear nexus between its statutorily delegated responsibilities and the ancillary role it proposes for net neutrality, without reverting to the sullied, protectionist past of ancillary jurisdiction.

Some observers may argue that such a “Title I” approach to net neutrality does not in principle prevent the FCC from exercising unlimited power over Internet communications. That’s overstated in my view. First, the Supreme Court’s 1970s decisions on ancillary jurisdiction (Midwest Video) hold that ancillary jurisdiction us not “unbounded.” Second, from a legislative perspective it is obvious that an administrative agency acting on the basis essentially of implied power cannot do anything broader under a general “public interest” standard than it could if acting under the express jurisdiction delegated by Congress. Specifically, while Title II authorizes full, rate-of-return common carrier regulation, the FCC would overstep its bounds imposing parallel rules under Title I ancillary jurisdiction. Third, the extreme critique from conservatives that agencies cannot be permitted to do anything without express congressional authorization really doesn’t apply; Congress has granted Title I authority over all interstate communications, it just has not fleshed that out with detailed standards.

More problematic are current reports that the FCC is considering relying on Section 706 of the Act, which urges the agency to promote “advanced telecommunications” services, as its ancillary jurisdiction hook for net neutrality. That’s inane, because the Commission in the 1990s ruled over and over again that 706 was not a basis for regulatory power. This means that using 706 as the nexus for ancillary jurisdiction will necessarily stoke a hotter fight over the FCC’s reversal of its statutory interpretation, a double whammy.

The better linkage is to the basic legislative commands (e.g., Section 201) that direct the FCC to ensure just and reasonable communications and broadcasting services for users. It cannot be disputed that if current trends continue, VoIP and Internet video could and well may eventually displace POTS and cable/broadcasting, in which case there would be nothing left with which the FCC could fulfill these elementary responsibilities if such IP-based services, which do not represent “telecommunications,” “cablecasting” or “broadcasting” in traditional statutory terms, must remain forever and completely unregulated.

A broader and more cogent question is, if the FCC takes this approach, would that not create a system in which an agency decides for itself how far to go when Congress fails to update its underlying statutory power to reflect technological change? Yes, it would. But it would not be Genachowski or the FCC creating this paradigm, it was the Supreme Court. A better legal system would have an administrative agency go back to Congress and ask for new powers if its old ones are being end-run by technology. As a practical matter, that could lead to gridlock, however, as in the communications arena general revisions of the Communications Act of 1934 happen very rarely — once in 65 years, far less than every generation.

So if politics is the art of the possible, it is possible for the FCC this Tuesday to make history, survive a judicial challenge and move archaic regulatory jurisprudence forward into a new era, stripped of its protectionist past. It’s also possible the Commission will be split politically, that left-wing proponents can convince some members that a principled loss is better than a compromise win, see Net Neutrality Supporters Question FCC’s Genachowski Plan | Techworld.com, or that as it has so many times in the past, the agency will fail to explain itself in simple terms the courts demand and can understand.

The Third Way of Title II reclassification was too cute for its own good. The Commission has a chance to correct that overreaching, but its internal bureaucratic tendencies to ambiguity and a “Chinese menu” theme for jurisdiction threaten to blow up net neutrality again. GOP Opposition to FCC Net Neutrality Plan Mounts | enterprisenetworkingplanet.com. Far more principled, regardless of one’s position on the substantive merits and policy need for network neutrality, would be for the FCC to pick a single, simple nexus. It’s not cute, it’s not expansive, but it would work. The question is whether in this highly polarized legal and political environment, the players really want anything to work at all.

Politics is always, in part, theater and sausage-making. That the law and public policy are the byproducts of such superficial pursuits remains a frustration, but in the United States it’s one we all have to live with, and one some pundits are convinced preserves the republican tradition of limited government. I for one hope the FCC keeps a more modest agenda tomorrow and moves the net neutrality debate closer to a conclusion, instead of adding fuel to the legal and policy fires that have raged on this issue for years.

This is the opening paragraph of an article by this author appearing today in the Fall 2010 issue of Icarus, the newsletter of the ABA’s Communications & Digital Technology Industries Committee, Section of Antitrust Law. “If the issue of broadband reclassification is not addressed with sensitivity to the history and traditions of FCC common carrier regulation, one can all too easily arrive at conclusions that simply cannot be squared with the legal framework applied to telecommunications for more than 30 years.”

The highly polarized debate over so-called net neutrality at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) exposes serious philosophical differences about the appropriate role of government in managing technological change. Neither side is unfortunately free either from hyperbole or fear-mongering. And neither side is completely right.

Read the whole essay. It’s provocative.

Note: I have not appeared as counsel for any party to the FCC’s current net neutrality NOI proceeding and was not paid to write this essay (despite what my colleagues and clients in the public interest community may claim). I represented Google in the past but now am ethically precluded from doing so because my law firm has a conflict of interest, being adverse to Google in an employment age discrimination case before the California Supreme Court. The article nonetheless does not reflect the views or opinions of my firm or any of my clients, past or present.

According to the New York Times, Texas attorney general Greg Abbott has launched an antitrust investigation of Google, based on the concept that deviations from “search neutrality” are anticompetitive and unlawful. Texas Attorney General Investigates Google Search | NYTimes.com.

The examination involves the fairness of Google search results, a concept called search neutrality. Some companies worry Google has the power to discriminate against them by lowering their links in search results or charging higher fees for their paid search ads.

This is utterly ridiculous. Google does not compete with the companies listed in its search results, but instead with other search engines for advertising. Anything Google may or may not do — and its mathematical algorithms leave precious little room for human bias — in Web search query results has no effect whatever on advertising competition. Search is by definition subjective because someone or something has to rank and order sites, but more importantly it is a free product. If anything, search bias would harm Google and help its search competitors (principally Microsoft-Yahoo!) by giving them a competitive advantage for search users looking for so-called “objective” Internet search results.

And in the only relevant market that counts — advertising — search neutrality is completely irrelevant. Even if advertisers pay for higher listings in search placement, as they can do for all Internet and search advertising (including “sponsored” or “promoted” search results on every major search site), that’s no different from paying for a full-page or inside front cover ad in a traditional magazine or newspaper. In the marketplace, that’s a completely acceptable, in fact desired, method of competition.

Now the search neutrality complainants argue that Google can “leverage” its search dominance into other markets. For instance, they say:

with its so-called Universal Search setup, Google is using its search engine monopoly — which controls an estimated 85 per cent of the global market — to unfairly favor its own services over those of its competitors. Universal Search transforms Google’s ostensibly neutral search engine into an immensely powerful marketing channel for Google’s other services. [I]t allows Google to leverage its search engine monopoly into virtually any field it chooses. Wherever it does so, competitors will be harmed, new entrants will be discouraged, and innovation will inevitably be suppressed.

Why the [EU] Google Antitrust Complaint is Not About Microsoft | The Register

As any antitrust lawyer knows full well, “leveraging” as a competitive concern is not unlawful and represents a discarded, 1960s-era theory of antitrust law. So this Texas investigation is really social policy (and bad policy, at that) on search engine technology masquerading as an antitrust issue. Get with it, A.G. Abbott, and be honest about what you are doing, which has nothing at all to do with competition or antitrust.

Even worse, if the Times’ sources are right, it seems that Microsoft itself, and my old antitrust colleague Rick Rule of Cadwalader, are behind the investigation.

The Texas attorney general has asked Google for more information on several companies, Google said. They include Foundem, a British shopping comparison site, SourceTool, a business search directory and myTriggers, which collects shopping links. In [a] Google blog post, [a company rep] drew an association to Microsoft. He said that Microsoft finances Foundem’s backer and that its antitrust attorneys represent the other two. Foundem is a member of the Initiative for a Competitive Online Marketplace, a European group co-founded and sponsored by Microsoft. SourceTool and myTriggers are clients of Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft, the law firm that represents Microsoft on antitrust issues.

Note also that Foundem runs the searchneutrality.org Web site.

I don’t agree with guilt-by-association for lawyers in private practice. But if Microsoft is financing these complaints, that just reinforces my long-held view that antitrust laws can be and frequently are used strategically to restrain competition and block rivals just as much as they can and should be used to pry open markets from dominance by monopolists.

You pick which motivation is at work here. My conclusion is obvious.

In a decision that has already generated a huge volume of commentary and predictions,1/ just three days ago the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit reversed a contentious ruling by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) from 2008 that penalized Comcast Corp. for violating the Commission’s “network neutrality” Internet principles. Comcast Corp. v. FCC, No. 08-1291 (D.C. Cir. April 6, 2010). Those principles include a content access requirement that the FCC said prohibited broadband operators and other Internet Service Providers (ISPs) from using network management practices to block or “throttle” specific Internet Protocol (IP) based services, such as the peer-to-peer, or P2P, filing-sharing communications offered by BitTorrent.

The Court’s opinion represents a devastating blow to the FCC’s assertion of ancillary jurisdiction authority over the Internet, ISPs and IP-based services. It calls into question how, if at all, the agency can implement many of the proposals put forward in its recent National Broadband Plan (NBP) and the “open Internet” proceeding launched last fall to codify those 2005 net neutrality principles (plus two additional rules proposed by new FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski). And the D.C. Circuit decision calls out for resolution by Congress of the jurisdictional void created — a call some legislators have already heeded.2/

Yet much of this crisis mentality appears unwarranted. There are accepted legal bases the FCC could employ to achieve a substantial part of its objectives related to consumer protection on the Internet. Where the FCC may not by statute operate, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) — which for several years has been biting at the bit to oversee broadband competition and consumer protection — can. That is because the Comcast decision compels the conclusion, at the very least, that broadband is not a “common carrier” service over which the FCC enjoys exclusive federal jurisdiction. The FCC’s proposal in its recent broadband plan that the agency apply universal service funds to subsidize broadband deployment in rural areas is likely not threatened materially by the Comcast decision. And the larger public policy fight over so-called “reclassification” of broadband as a Title II service presupposes, incorrectly, that Title II treatment means subjecting IP-based services to the same, traditional public utility model of regulation as monopoly telephone providers. In short, the agency and Congress face a dizzying array of alternatives and options. Yet much of this crisis mentality appears unwarranted. There are accepted legal bases the FCC could employ to achieve a substantial part of its objectives related to consumer protection on the Internet. Where the FCC may not by statute operate, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) — which for several years has been biting at the bit to oversee broadband competition and consumer protection — can. That is because the Comcast decision compels the conclusion, at the very least, that broadband is not a “common carrier” service over which the FCC enjoys exclusive federal jurisdiction. The FCC’s proposal in its recent broadband plan that the agency apply universal service funds to subsidize broadband deployment in rural areas is likely not threatened materially by the Comcast decision. And the larger public policy fight over so-called “reclassification” of broadband as a Title II service presupposes, incorrectly, that Title II treatment means subjecting IP-based services to the same, traditional public utility model of regulation as monopoly telephone providers. In short, the agency and Congress face a dizzying array of alternatives and options.

This post has two parts:

- First, I review the proceedings leading up to and the substance of Circuit Judge David S. Tatel’s opinion for a unanimous three-judge panel of the court of appeals.

- Second, I put the decision into context and explore ways in which the FCC could react, including the legal rationale(s) the agency would need to develop on remand.

Both portions of the essay, however, are of necessity general overviews. A complete examination of this rather wonk-ish area of communications jurisprudence requires a longer treatise than warranted for such a time-sensitive post. I encourage readers to address these issues in greater detail in comments below and to the FCC in its open Internet NPRM proceeding.

1. The Comcast Decision

The FCC had classified cable modem service as an information service under the bifurcated regulatory approach of Computer II and the 1996 Telecommunications Act, a ruling affirmed by the by the Supreme Court in NCTA v. Brand X, 545 U.S. 967 (2005). Nonetheless, the Commission later developed a set of four network neutrality principles adopted in a 2005 “policy statement.” These were intended to protect what the agency perceived as a threat to the open character of the Internet if vertically integrated content providers blocked or discriminated against other Web sites and content in order to favor their own IP-based services.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

Much like the assumptions underlying the NBP, the net neutrality principles aspired to an Internet free of any provider’s control, giving every end user access — with little or no permissible differentiation among services or even packets — to all content available anywhere, anytime. (They also harkened to a similar failed effort by public interest advocates, in the late 1990s, for what was then termed “cable open access.”)

Whether or not regulatory intervention is needed to ensure this result was not at issue in the Comcast appeal, but it was central to the FCC’s enforcement action that triggered the case. Faced with the reality that file-sharing end users were consuming huge amounts of bandwidth, Comcast deliberately limited their ability to use P2P client-side applications by first outright blocking, and later imposing network management controls on, BitTorrent IP traffic, so that the latency-sensitive applications of the majority of its Internet customers would be delivered uninterrupted. Some consumer advocates alleged that the cable giant did so in order to protect its own on-demand video programming services from potential competition. Comcast stopped the practice after the story came out but was later discovered to have misled the Commission with its initial responses, and the company never revealed to customers that some IP traffic was not being routed with the same throughput as other services. The FCC subsequently imposed reporting and disclosure requirements on Comcast’s traffic management practices, based on the 2005 policy statement, which the agency had not promulgated as actual rules or regulations.

Comcast appealed that decision. The FCC defended its actions on the ground that, even though Internet broadband is not a telecommunications service subject to Title II of the Act, the agency has ancillary jurisdiction to regulate. That ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, sometimes confusingly referred to as “Title I jurisdiction,” is based on a 1960s-era decision by the Supreme Court in which the FCC had restricted cable television by regulation in order to protect traditional TV broadcasters, over which the agency enjoyed express statutory authority. In Comcast, the D.C. Circuit concluded that under that approach, ancillary regulations must be ancillary to something explicit in the Act, in other words that the Commission must show that its traffic management directive was “reasonably ancillary to the … effective performance of its statutorily mandated responsibilities.” Finding that the FCC had not done so, the Court reversed.

Without detailing each of the statutory hooks advanced by the Commission, it suffices to say that the agency did not seriously urge the court of appeals to sustain ancillary Internet regulation in order to protect its Title II, III (broadcasting) or VI (cable) jurisdiction over legacy services for which the Communications Act grants explicit regulatory authority. Instead the FCC urged that various general statements of public policy appearing in the 1996 Act amendments provided the necessary linkage. The D.C. Circuit rejected that contention, concluding that policy does not suffice under the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine as a statutorily mandated responsibility. The FCC also cited section 706 of the 1996 Act, which directs it to “encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans.” The Court likewise rejected that linkage because the Commission itself had long ago ruled that section 706 does not constitute “an independent grant of authority” to the agency.

These holdings, foreshadowed earlier by oral argument — see “Appeals Court Unfriendly To FCC’s Internet Slap At Comcast” [Wall Street Journal] — are relatively unsurprising. What is somewhat unusual is that, in its appellate positions, the FCC suggested additional grounds for an ancillary jurisdiction theory that had not been relied on in its 2008 order. The most cogent of these added rationales was that Internet openness and nondiscrimination is ancillary to the “just and reasonable practices” mandate of sections 201(b) and 202(a), applicable to telecom carriers. Judge Tatel’s opinion dismissed these post-hoc justifications not on the substance, but rather because Administrative Procedure Act precedent requires a reviewing federal court to sustain or reverse a regulatory order on the same grounds offered by the agency in its underlying decision.

Comcast’s challenge of the 2008 order had offered the Court the opportunity to overturn it on the narrower ground that principles, unlike rules, are not enforceable in company-specific adjudications. But the D.C. Circuit did not reach that question. Its analysis essentially concurred with dissenting Commissioner Robert McDowell’s criticism that “[u]nder the analysis set forth in the order, the FCC apparently can do anything so long as it frames its actions in terms of promoting the Internet or broadband deployment.”3/

The end result is that the FCC’s network neutrality principles are effectively dead, for now at least. The agency has various options available, but unless and until it develops either an alternative rationale under its existing statutory framework, or procures a new legislative grant of authority from Congress, it cannot police the practices of ISPs and broadband providers. It is to these alternatives and their viability that I now turn.

2. The Post-Comcast Regulatory & Legislative Environment

In the wake of the D.C. Circuit’s decision, network neutrality advocates urged the FCC to ensure Internet openness by “reclassifying” broadband as Title II telecom service. Gloating opponents opined that the FCC was properly chastised and should rein in its efforts to regulate what they view as an increasingly competitive market, in which most major ISPs have long ago pledged to respect net openness as a business matter. Meanwhile, Web-based grassroots campaigns, with typical rhetorical excesses, sprang up overnight to “save Internet freedom.”

The reality is somewhere in between. Had the FCC desired, it could have — and still might — justify its ancillary jurisdiction by articulating a relationship between broadband Internet access and traditional, regulated communications services. By declining to review the Obama Commission’s arguments based on the mandatory obligations of reasonable rates and practices under Title II, the court of appeals has all but begged the FCC to do so on remand. The problem with this approach, especially given the history of the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, is that it reflects a paternalistic, corporate welfare model of economic regulation which is out of favor as a policy matter with politicians, regardless of their party affiliation or ideology.

It would not, however, require much in the way of legislation to give the FCC explicit authority to adopt and impose network neutrality nondiscrimination rules. In its 2009 stimulus legislation, Congress allocated $7.2 billion for distribution by executive branch agencies in the form of grants to spur broadband deployment. A portion of those funds was expressly conditioned on grantees’ agreement in advance to comply with the Commission’s 2005 network neutrality principles. Unlike broader calls to completely rewrite the Communications Act in light of convergence, a legislative “fix” specific to net neutrality would not be unusually difficult. Whether there exists the political will and votes to do so, especially in the aftermath of the divisive healthcare reform debate, is unclear.

Nor does the Comcast decision by the D.C. Circuit necessarily spell the death knell for the Commission’s National Broadband Plan. Some of its proposals, such as privacy protections for broadband end users and truth-in-billing disclosure requirements for ISPs, would surely require new legislative authority. Yet the basic objectives of the plan, including its proposal to allocate an additional $16 billion in universal service funds to subsidize broadband services, are not necessarily invalid after Comcast. That is because section 254 of the Act likely allows the FCC to both collect USF contributions from and — as reflected in the E-rate program — use them for “advanced services” like Internet access. Nor does the Comcast decision by the D.C. Circuit necessarily spell the death knell for the Commission’s National Broadband Plan. Some of its proposals, such as privacy protections for broadband end users and truth-in-billing disclosure requirements for ISPs, would surely require new legislative authority. Yet the basic objectives of the plan, including its proposal to allocate an additional $16 billion in universal service funds to subsidize broadband services, are not necessarily invalid after Comcast. That is because section 254 of the Act likely allows the FCC to both collect USF contributions from and — as reflected in the E-rate program — use them for “advanced services” like Internet access.

The final FCC option is to reconsider its earlier rulings that Internet access services (at least when integrated with IP transport) are “information services” for purposes of the 1996 Act’s classifications. Some analytical jujitsu would obviously be required to achieve that result, since the agency needs to develop and articulate changed circumstances that rationally justify a reversal of its prior ruling. But since the Supreme Court has recently emphasized that the APA does not impose on administrative agencies any higher burden of justification to repeal or revise its rules and policies than to adopt them in the first place, the FCC conceivably might be able to satisfy that standard.

Much of the opposition to this sort of “reclassification” stems from the fear that characterizing Internet access as a telecommunications service would carry with it the full panoply of legacy Title II dominant carrier regulation, such as rate-of-return pricing, entry and exit licensing and the like. The two, however, are not co-extensive. It has been the law for several decades, codified by Congress in 1996, that the FCC enjoys the ability to refrain or “forbear” from regulation. Reclassifying broadband as a Title II telecom service could, at least hypothetically, be coupled with a simultaneous decision forbearing from application of most substantive regulations to ISPs.4/ Yet at least to public interest advocates, that would be viewed as a loss; in their regulatory paradigm broadband represents the new common carriage and should be offered on a quasi-utility basis. That perception will need to be changed if proponents of reclassification are to stand a realistic chance of persuading the agency and, more importantly, successfully withstanding judicial review.

Finally, under both the Bush and Obama Administrations the FTC has expressed a clear desire to exercise its own statutory jurisdiction over broadband services. Historically, the FTC is precluded from applying the Federal Trade Commission Act and its unfair competition and consumer protection standards to common carriers. But absent reclassification, broadband is plainly not a common carrier service under either the Communications Act or the FTC Act. As a result, although FTC Chairman John Liebowitz has not made a public statement to date in the wake of Comcast, most observers expect that agency to move relatively rapidly into broadband for purposes of filling the void left in the wake of the court of appeals’ decision.

Conclusion

Network neutrality is a complex, contentious and confusing issue. While the D.C. Circuit’s opinion is abundantly clear, it is not apparent how the FCC or Congress will respond and whether the agency will seek Supreme Court certiorari review to test the basis and scope of its ancillary jurisdiction. Having persisted formally since 2005, and as a matter of policy debate for more than a decade, net neutrality is not necessarily dead, it is just entering a new phase of consciousness. That it looks comatose is perhaps a mirage that will be evaporated with time.

Footnotes

1/ Court Limits FCC Power Over Internet,” Boston Globe, April 7, 2010; Editorial, “FCC Must Quickly Reclaim Authority Over Broadband,” San Jose Mercury News, April 7, 2010; “FCC to Start Writing Internet Rules After U.S. Court Setback,” Business Week, April 8, 2010.

2/ Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), chair of the House Committee on Energy & Commerce, announced almost immediately that he is “working with the Commission, industry, and public interest groups to ensure that the Commission has appropriate legal authority to protect consumers.” Waxman Statement, April 6, 2010. Earlier, in July 2009, Reps. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) and Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.) introduced H.R. 3458, the Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2009, to enshrine what the legislation terms “Internet freedom” into law. However, In 2006 Congress failed to pass five bills, backed by groups including Google, Amazon.com, Free Press and Public Knowledge, that would have handed the FCC the power to oversee network neutrality compliance.

3/ See also R. McDowell, “Hands Off the Internet,” Washington Post, April 8, 2010.

4/ In response to concerns voiced regarding reclassification, Rep. Markey said that even under Title II, the FCC could forbear if it wanted to” and that in the past it had “availed itself” of that power. “We shouldn’t pretend that going back to Title II would mean that the earth would stop spinning on its axis and it would be the end of times,” he added. See “Concerns About Title II Reclassification Aired at House Hearing on Broadband Plan,” T.R. Daily, April 8, 2010.

There has been a lot of talk, debate and criticism — leveled at Google, Microsoft and other major Internet content providers — about censorship of Internet content by the government of China. Google v. China: Principled, Brave, or Business As Usual? [Huffington Post]. The assumption most of these pundits make is that mandatory filtering and blocking of the Internet is a policy embraced only by repressive or authoritarian regimes. That’s not at all correct.

Iran's Green Revolution Western nations are just as bad; worse in some ways. “Enemies of the Internet”: Not Just For Dictators Anymore [ReadWriteWeb]. As a few for instances:

Reporters Without Borders recently released a penetrating study of government Internet censorship, titled “Enemies of the Internet 2010.” It cogently observes:

Western democracies are not immune from the Net regulation trend. In the name of the fight against child pornography or the theft of intellectual property, laws and decrees have been adopted, or are being deliberated, notably in Australia, France, Italy and Great Britain. On a global scale, the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), whose aim is to fight counterfeiting, is being negotiated behind closed doors, without consulting NGOs and civil society. It could possibly introduce potentially liberticidal measures such as the option to implement a filtering system without a court decision.

So Internet censorship is alive and well in the world’s “progressive” industrialized nations. The liberating technology of the Web is under assault because, as in 2009’s “green revolution” in Iran via Twitter, it can catalyze viral growth in political opposition and tends to harbor folks, like pedophiles, who’s activities are politically disfavored (even repulsive). No one lobbies for child pornographers, after all.

Just do not operate under the misimpression that it is only Saudi Arabia, Syria, North Korea, Vietnam, China and the like that censor Internet content. Almost all governments do it. The United States, with its constitutional First Amendment protection for free speech, and the Scandinavian countries — where the Pirate Party was victorious in Swedish parliamentary elections — which have classified Internet access as a fundamental human right, are the exceptions. This blogger, for one, hopes the exception swallows the rule. One can always hope.

That’s what Andrew Orlowski of the UK’s The Register calls Friday’s decision by the Federal Communications Commission to cite Comcast for unlawful violation of "network neutrality" principles. One can agree or disagree with the proposition, endorsed by FCC Chairman Kevin Martin, that Internet users should be free to reach any site without interference by their ISPs.

“We are preserving the open character of the Internet,” Martin said in an interview after the 3-to-2 vote. “We are saying that network operators can’t block people from getting access to any content and any applications.”

But it is just absurd to conclude that any federal government agency should be allowed to issue what it expressly terms a set of non-binding "principles" and then make an official finding of illegality when a company fails to follow those principles. Confusing is an understatement here. Dissenting Commissioner Rob McDowell’s complaint that the FCC here is actively regulating the Internet — or at least historically unregulated "enhanced services" offered by ISPs, unlike common carrier telecommunications services — is spot on.

|

|