A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

[Part I of this series of essays can be found at this permalink, Part II at this permalink].

3. Trademarks, Genericide & “Twittersquatting”

Let’s assume, for purposes of discussion, that social media content — not limited to Tweets — cannot be trademarked. Whether that is correct will be ultimately determined, at some point, by a combination of the PTO and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. What that (reasonable) assumption indicates is that trademark law is far more important for existing trademark holders who either (a) venture into the social stream and real-time Web in order to market and promote their brands, or (b) are confronted with third-parties using their trademarks, whether for commentary or profit, without consent, than it is for social media users generally.

(a) The Aspirin of Social Media. Trademarks are property rights, both under US common law and pursuant to federal statute, the validity of which often hinges on two discrete issues — first use and “genericness.” People tend to forget that Bayer AG first invented aspirin in 1897 but lost its rights to the brand name in the United States by allowing it to escape into the public domain, i.e., go generic or commit “genericide,” a tragic commercial fate shared famously by Duncan Yo-Yo Co. (yo-yo) and Otis Elevator Corp. (escalator), among others. Generic terms of course cannot be trademarked. As a result, such companies and products as varied as Xerox (photocopying), Kleenex (facial tissue) and Johnson & Johnson (band-aid) have stepped up outreach and litigation efforts to curtail use of the trademarked brands as nouns and to constrain their own usage, for instance by changing advertising jingles to add “brand” to the name (going from “I’m stuck on Band-Aids, ’cause Band-Aid’s stuck on me” to “I’m stuck on Band-Aid brand, ’cause Band-Aid’s stuck on me.”)

Welcome to Web 2.0, corporate IP police! Your task in protecting against genericide has become an order of magnitude harder because social media is immediate, difficult to search and presents such massive volume of content that periodic review of even a portion of it is clearly impossible. But as the historic lessons show, doing nothing risks colloquial usage of marks in ways that conflict with trademark holders’ long-term interests. There is no substitute for perseverance, hard as it may be in the context of real-time social streams.

Perhaps most vexing is that these very risks can be presented by a company’s best customers, its “fans.” As PR specialist Rob Clark of the SMG Group notes:

So we all know the story. Imagine, a group of faithful enthusiasts falls in love with Super-Duper Brand (for the purposes of this illustration I’m using a fictitious name). They start a forum at superduperrocks.com, the maintenance of which they cover by selling superduperrocks t-shirts and other merchandise. A lawyer for Super Duper stumbles upon the site and fires off a standard cease and desist letter to attend to the trademark infringement. The community freaks out, both in terror of what a visit to court may cost and in anger of being turned on by the brand they adored and revered. The pundits point a spotlight on the issue and chuckle over what a stumble, what a gaffe, “who could possibly be foolish enough to attack your greatest evangelists?” Those who rail against the new media tools will waggle their fingers and declare, “These interwebs will doom us all.”

That’s a debacle in the making. The IP lawyer was obviously correct, but crowd-sourced demand letters will likely do more to alienate fans than protect the mark. The balance between heavy-handed legal cease-and-desist letters, litigation and consensual licensing of permissible uses represents a major challenge to trademark holders in the emerging era of social media.

(b) Safe Harbors, Impersonation and Infringement. So if that’s not bad enough, take the question of how trademark holders can prevent others from infringing (or diluting) their marks by scarfing up the words as profile identifiers on social media sites. The short answer is, like all mark protection activities, vigilance. Yet as addressed in this section, at present the law is still developing and the statutory rules established to deal with improper use of protected trademarks on the Internet — mainly in the domain name and copyrighted content (music, movies, etc.) contexts — do not squarely apply to social media and the real-time Web.

It would be a pleasure, for my ISP and Web site clients, to report that the statutory safe harbor granted to Internet access providers — commonly known as “notice-and-takedown” — protects them against litigation for trademark infringement by social media users. But that’s not necessarily the case at all.

First, the immunity provided to interactive computer services under the Communications Decency Act (47 U.S.C. § 230) applies only to screening and blocking of child pornography and other offensive Internet content, while the DMCA safe harbor in 17 U.S.C. § 512 is inapplicable if a “service provider” receives any “financial benefit directly attributable to the infringing activity” and “has the right and ability to control such activity.” Whether the courts will construe these terms expansively is unclear. Yet it is clear that at least some social media providers both receive financial gain (which may not mean profitability, by the way), including advertising revenues, and have the ability to arrest infringing conduct by users. So while removing allegedly infringing UGC or profiles is a good business practice, it does not mean legal liability is eliminated.

Second, the provisions of the Anti-Cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(d), limit the protection accorded vis-a-vis trademark holders to entities assigning “domain names,” defined narrowly as “alphanumeric designation which is registered with or assigned by any domain name registrar, domain name registry, or other domain name registration authority as part of an electronic address on the Internet.” Social media profiles do not yet fall under this statute, at least facially.

So even in the case of simple “Twitterquatting” — the allocation by a social media network provider of a user name to someone who is either not the real person or who is using a trademarked phrase without permission — there is no compelling case to be made today for statutory immunity. Recall that, in the early days of the commercial Web, Network Solutions (now VeriSign) was sued frequently by trademark holders under contributory infringement, conversion, negligence, unfair competition and other traditional causes of action for registering trademarks as domain names to people without legal rights to the marks. See, e.g., Lockheed Martin Corp. v. Network Solutions, Inc., 193 F.39 980 (9th Cir. 1997). And more recently, Google has litigated a series of cases in which famous brands (Vuitton, etc.) have alleged, with mixed results, that its AdWords program represents use by Google, as opposed to the advertisers paying for such keywords, of a protected mark in commerce, thus exposing Google to potential damages liability. (I personally don’t agree with this legal theory, but the fact is that it has been accepted by a minority of courts.)

All of these theories, which parallel the claims brought by AOL and other ISPs against spammers before Congress made unsolicited commercial email illegal with the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003, can be asserted unless and until legislation is passed creating a national standard and preempting state law. For instance, in his well-publicized (but later withdrawn) lawsuit against Twitter, Tony La Russa claimed that use of his name by another Twitter member constituted Lanham Act violations (trademark infringement, false designation of origin, dilution of a famous trademark), invasion of privacy under California Civil Code § 3344 and misappropriation of name and likeness.

It is no wonder, then, both Twitter and Facebook have established means by which rights holders can protect their trademarks from unauthorized use. For Facebook, these include:

- Filing their trademark(s) online with Facebook, which will prevent any third-party users from acquiring the filed trademark as a username. (Filing requires the name of the company, the trademark to protect, the federal registration number of the mark and the filer’s title and email address.)

- Not authorizing transfer or sale of user names in the hope that this will eliminate squatting or profit-driven transfers.

- Maintaining an online IP Infringement form which allows rights holders to protest after-the-fact unauthorized uses of their intellectual property.

Not unusually (see Part II), Twitter does things a little differently. The Twitter terms of service (ToS) grant it the right to remove or suspend unilaterally any account that appears to or is claimed to violate another’s trademark rights. These notice-and-takedown provisions are based on a “clear intent to mislead people” as the test for suspending unauthorized accounts. However, they explicitly allows parody impersonation, using a standard of whether a “a reasonable person be aware that it’s a joke” as the criterion for a parody. (The fact that the La Russa impersonator prominently labeled his profile as a fake plainly did noting to deter litigation, of course.) And those same guidelines have not stopped corporations from suing Twitter when they suspect others are “diluting” their marks, even before response to a takedown demand. Twitter has also responded as a business matter with a so-called “verified account” program for public figures.

Now on the substance of parody or so-called “gripe” users, trademark law is gradually becoming clearer, and works to favor the social media site rather than the personality. There are numerous obstacles with use of federal trademark law to prosecute a gripe user. Trademark infringement claims require that the defendant use the plaintiff’s mark, without consent,”in commerce” — a term that generally refers to the sale of a product. Parodies and product criticisms may use a plaintiff’s name or mark,but typically not to sell anything, rather to complain about or poke fun at the company. Trademark claims also demand that the defendant’s unapproved use of the mark must have confused reasonable consumers. However, because such third-party sites and content typically attack or lampoon the trademark holder, there is little risk that consumers could ever reasonably believe that such a site was operated by the trademark owner.

A recent Sept. 2009 decision by U.S. District Judge T.S. Ellis in Virginia, Bernard J. Carl v. BernardJCarl.com, focused on another element of trademark law — whether an individual’s name is a protectable trademark. The general rule is that names (first or last) only qualify as trademarks if they have acquired a distinctive “secondary meaning.”

Controlling circuit authority clearly classifies the use offirst names or surnames as descriptive marks, which are inherently non-distinctive and accordingly are not protected under the Lanham Act absent a showing of distinctiveness. Thus,descriptive marks may gain the protection ofthe Lanham Act if they become distinctive by acquiring a secondary meaning within the relevant purchasing community — that is, a substantial number ofpresent and prospective consumers.

So, for instance, “Martha Stewart” probably has acquired a secondary meaning, to refer to her home decoration, gardening and food business. The same problem would arise for claims of cybersquatting, because, according to Judge Ellis, to garner protection under the ACPA a personal name must have acquired secondary meaning at the time of its registration. The implications for social media sites are obvious, namely that even if there is a legal basis to challenge so-called “Twittersquatting” for celebrity impersonation, it probably does not lie in the realm of trademark infringement.

(c) Trademarks and Deep Pockets. From the legal to the practical. All of the above is without regard to the fact that, like NSI in the 1990s, those who believe their interests or business have been damaged by use of a name, mark or other content by a social media subscriber are — as an economic imperative — inclined and very well incentivized to name as the principal defendant the company running the social network. When Hasbro had a problem with a Facebook application developer’s take off on “Scrabble” for a wildly popular Facebook game dubbed “Scrabulous,” it acted against Facebook under the DMCA, not (at least initially) against the smaller, and less well-endowed financially, developer. Likewise, when one game coder believed another had stepped on his trademark, he sued Facebook for infringement.

What these and many other anecdotes indicate is that when setting up and operating any social media site, a Web developer must take into account that it is the most visible, and some might say vulnerable, party to use of the litigation process for what I called “legalized blackmail.” (Note, I have not trademarked that phrase, so you are free to use it!) Litigation defense is a cost of doing business in modern America. And since the issue of knowledge is key to trademark defense — under the reasoning in Tiffany v. eBay Inc., social networks could be held liable for username squatting or infringement (on a contributory infringement theory), if they continue to provide services to users they know or have reason to know are engaging in infringement — programs that terminate user membership privileges at the slightest hint of unlawful use of content or marks are the best insurance.

Given the uncertainties surrounding the nascent law of social media, which as noted in Part I will most likely evolve out of the cauldron of litigation, the burden of litigation as a cost of doing business may be a steep one indeed. So as users, expect to see a whole array of self-protection measures by social media vendors. “Verified accounts” and trademark take-down complaints are just the very early start. The days of Twitter being praised for its laid-back, touchy-feely attitude towards trademarks are over, I believe, in just a short six months. And that, readers, is the speed at which things change in our world of the real-time Web!

In Part IV of this series of essays, we address the broader context of social media law, including whether there is anything really new here, or just “old wine in new bottles.”

[Part I of this series of essays can be found at this permalink].

2. Who Owns User-Generated Content?

Who owns user-generated content (UGC) posted to social media sites? This is but one of the many vexing issues presented by the emerging law of social media, albeit one of great interest to users, corporate subscribers and social networking providers alike. After all, if possession is 9/10 of the law, then the natural, lay reaction to the question of who owns social media UGC is “the Web site, of course.”

That’s not exactly correct, however. One must differentiate among the various forms of intellectual property (IP) law potentially applicable here. Copyright, a matter exclusively of federal law, is available for original expressions (with or without registration), but is always subject to “fair use.” Trademarks and their service mark complements are available for unique names, phrases and logos associated with commercial products and services, but are limited to narrow classes of expression and ordinarily — unlike copyright — must be expressly claimed. Finally, patents are available for inventions (products, processes and methods), and give the patent holder (a/k/a patentee) the power to prevent anyone else from using the protected invention, but only arise when a patent is officially issued by the Patent & Trademark Office (PTO).

(a) Social Media and IP Law. Each of these bodies of law, and the respective rights and obligations they create, has a different impact on social media generally. For instance, Twitter owns a trademark on the company’s name, but was denied registration of a trademark on “Tweet.” And in a provocative change last February, one eliciting a firestorm of user criticism, Facebook modified its terms of service (ToS) to grant the site a perpetual license on UGC even after a subscriber terminates his/her membership and removes photos and other UGC from their page. These two recent examples illustrate not only that IP law in part depends on the eye of the beholder, but more importantly that even within the social media space, there is no present consensus on just what is protected, what is public domain and what is somewhere in between.

Let’s start with the basics, then. Copyright cannot be claimed on information, only on expressions. So the information in a database or software application cannot be copyrighted, but the organization of a database and the actual code (whether in a scripting language or machine code) for a program are considered expressions subject to copyright. One would not, for instance, violate Microsoft’s copyrights by designing a word processing program that replicated functionalities of MS Word, but copying of the underlying code would be unlawful. (Don’t take this too literally, however, because the issue of software patents, including those granted to Microsoft — one of present controversy in the US — could prevent another coder from achieving the same functionality under the patent law doctrine of “equivalents,” whether or not code was actually purloined.)

Unless, that is, the copying were protected by the so-called fair use doctrine, codified at 17 U.S.C. § 107. This exception allows use of some, but not all, of an original work by another (with or without attribution), and is the basic reason why bloggers who quote portions of other posts are acting lawfully. On the other hand, lifting the entire portion of any article, whether blogged or on a traditional media site, is typically illegal without the consent (i.e., license) of the copyright holder. Yet again, if the expression itself is already in the public domain, then courts will not uphold a copyright claim, concluding either that the author “impliedly” licensed the content, abandoned any copyright in the expression, or that the material is not copyrightable in the first instance because not original.

Putting all these basic principles together yields precisely the answer posed for social media legal questions generally in Part I of this series — “it depends.” If a blogger structures his site with a full Creative Commons license, then nothing posted is subject to copyright because he has abandoned such a claim. If a Facebook user posts photographs to his or her Facebook page, and makes them available to friends, a copyright claim likely would not lie against those friends if they used the photos without permission. But, as we shall see below, these are the easy situations in which application of IP principles is (relatively) clear.

(b) Are Tweets Copyrighted? This was the question, first posed in the blogosphere by Mark Cuban in May 2009 (“Are Tweets Copyrighted?“), addressed in part in an earlier post. To summarize, a Tweet, like any other expression, can be copyrighted if original, not public domain and not impliedly licensed. But neither Mark nor anyone else (as far as this author knows) has addressed whether a Tweet, at 140 characters, is inherently too short, i.e., too superficial, to be deemed an original expression for purposes of copyright. Compare, for instance, Pat Riley’s famous trademark in the early 1990s on “three-peat” while with the L.A. Lakers. Whether the same phrase could be copyrighted is doubtful.

The point here is that social media sites cannot create rights that otherwise do not exist in the law, but can narrow or waive rights otherwise held by users with their ToS agreements. The conclusion that because Twitter has disclaimed ownership of Tweets the tweeting user must necessarily own them is a false syllogism. In other words, the language in the Twitter ToS to the effect that “what’s yours is yours” and that ”[the Twitter account owner] profile and materials remain yours‚” is merely prcatory, as lawyers say. It doesn’t bind anyone and certainly cannot govern if the copyright claim is disputed in court.

Copyrightable contents must be original, an expression (not a fact or opinion) and not merely an idea. If the material you post through Twitter isn’t copyrightable to begin with, it will not mystically transform into protectable content merely by being Tweeted, and decidedly not because, as between Twitter and its users, Twitter has technically disclaimed ownership. Hence, as one writer cogently observed:

The long and short of it is this: if 90% of all Tweets are nothing more than recitation of facts. That means that about 90% of Tweets are not protectable. For the other 10%, we’re not done with you yet. It’s all in how those facts are stated.

Twitterlogical—The Misunderstanding of Ownership. [Note to author Brock Shinen: this is most decidedly fair use!!] Also useful in this regard is an interesting blog post by PR specialist Evan Hanlon on the conflict between social media and copyright law as applied to digital music sharing.

Well, it’s not really “how the facts are stated” so much as whether the expression is original and not somehow “donated” to the public domain by posting on Twitter. A serious argument can be made, with which I tend to agree, that Tweets inherently cannot be copyrighted, even IF original, because the very act of posting them on Twitter means the entire world can see them, without the author’s permission. So unlike other social media sites, where access to UGC can be controlled, at first blush it seems that unless one has a “private” Twitter feed, one cannot claim copyright in Tweets because the very nature of tweeting is that the tweeter intends that anyone in the world can view, link to and use his or her Twitter UGC.

(c) Tweets and Fair Use. Indeed, the underlying rationale for according Tweets copyright protection breaks down entirely when one examines fair use. First, if copyright applies to public Tweets, then traditional media’s use of them to date — including reading or displaying in full on television — cannot be fair use because it copies the entire “expression.” Second, the accepted practice of “retweeting” (RT) contradicts the basic principles of copyright law. Because users can (and do) retweet without limitation, it is a fair conclusion that posting a Tweet is an implied copyright license, at least for duplication by others on the same site. As Mashable’s Pete Cashmore noted, taking another user’s Tweets is not “copying,” but “retweeting. And I love it..” That comes at the question from the perspective of third-parties, rather than the putative content owner, but cogently expresses the idea that application of copyright to Tweets is problematic, at best.

Now it remains true that general legal rights and obligations can be varied by agreement. And to date, courts have largely accepted the de facto use of checkboxes to indicate a user’s “acceptance” of ToS contracts, drafted entirely by Web site owners, to which they have had no input or ability to negotiate. (California recently signaled a possible change to this assumption with a controversial decision as to software “shrink wrap” agreements, however.) So, assume we are now dealing with photos instead of 140-character messages. No one would argue that photos cannot be (or generally are not) copyrightable original expressions. So then — unless the act of posting itself is abandonment of a claim of copyright — ownership of rights on photos will be determined by the ToS of the social media Web site owner.

(d) Style or Substance? Here we have an interesting contrast. Facebook, as noted, has advocated a rather different view of copyright, insisting on a royalty free, perpetual license to UGC as a condition of posting — indeed, a license that survives death or withdrawal. Absent some independent constraint, like unconscionability, those ToS licenses are valid, regardless of a user’s rights under the Copyright Act. And Facebook has a point, because once “shared” with friends on the site, photos are (or at least can be) copied to some or all friends’ pages. Twitter, in contrast, says that UGC is always the user’s property. (As careful lawyers, however, Twitter’s counsel also include an express ToS license, even though retaining the “what’s yours is yours” language.)

This license is you authorizing us to make your Tweets available to the rest of the world and to let others do the same. But what’s yours is yours — you own your content.

Yet the inherently public nature of Tweets, which are “shared” with others by posting but not (except by retweeting) cross-posted as on Facebook, means that Twitter really does not need a license to the content of Tweets, since it does nothing with them other than what the user specifically intended, namely posting them on a Web page.

In the final analysis, this difference is probably more cosmetic than substantive, more about optics than legal rights. Twitter has designs to become the real-time Web’s “utility” infrastructure, so its business model does not require, indeed conflicts with, the company’s ownership or licensing of UGC. Facebook, in contrast, is a walled community, constantly devising ways for user to spend more time (whether or not productive or addictive) on the site. So for Facebook, and especially because any element of a Facebook profile can be made private, including to all other Facebook members, its buisness needs licensing for the model to work. They are different business models, driving different views of IP law. Just like beauty, in other words, the answer is in the eyes of those with the content itself!

And, BTW, if you think the above is thorny or complex, just ponder for a moment the even more opaque question of who owns UGC after the user dies. We’ve needed living wills and medical powers of attorney for more than a decade to exert personal control critical health care decisions. Will we also need Web-proxies authorizing our medical decision-makers and heirs to access and control UGC? Yup, you know the answer — “it depends.” A week or so after I first posted this essay, in fact, Facebook announced that it will “memorialize” profiles of deceased members if their friends or family request it. Facebook Keeps Profiles of the Dead [AP]. That may not be the law, as of now, but it does suggest that social networks will increasingly be required as a practical matter to develop their own policies, based on the interests and needs of their users, on how to address death in cyberspace.

In Part III of this series, we explore trademarks, genericide & “Twittersquatting.”

Who owns user generated content (UGC) posted to social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, MySpace and the like? How has or will the law evolve to deal with the different, and sometimes unique, modes of personal interaction (with others and with information) made possible by social networking technologies? These are just a few of the legal issues presented by the emergence of social media, one of the fastest growing — and most addictive — forms of Internet-based communication in the relatively brief history of the medium.

1. It Depends

Before diving into the answers, a few words of caution, however. The law evolves slowly and rarely keeps up with technology. Legislation typically solves problems from the PAST decade, not the ones facing Web site operators, users, content providers and ISPs in the immediate future. So if readers believe you can wait for the U.S. Congress (or even state legislatures) to solve the legal status of social media, that is myopic. Far more likely is repetition of the pattern exhibited over the past 15 years with respect to a variety of Internet issues, from spam to judicial jurisdiction. A rather long, and not altogether satisfying, process of applying legacy legal rules to a new technology, progressing in fits and starts and formed principally in the cauldron of litigation.

That is not the optimal way to establish law or policy, but it remains the default in any legal system, including the United States, where citizens have recourse to both a legal code (statutes) and judge-made law (common law). Disputes must be resolved even where, as is all too typical, the statute-writers have not yet dared to tread. The consequences for “social media law” are enormous. While hundreds of millions of Internet users post content to and exchange messages and information via social media on a daily basis, the legal rights, duties and status of that information remain essentially unformed. It is a common impression that lawyers always answer questions with “It depends,” but for social media, those answers are 100% correct. Any effort to compile “the law” of social media — including this essay — is in reality a prediction of how courts will decide cases brought before them. It’s an educated guess, at best.

Social media is unique in some ways (one-to-many, public sharing, etc.), but in other ways is just new communications forum — old wine in new bottles, as the old legal (and biblical) saying goes. Witness St. Louis Cardinals’ baseball manager Tony Larussa’s lawsuit versus Twitter, based on an allegation of so-called “cybersquatting” arising from use of LaRussa’s name as a Twitter “handle” by another subscriber, or criminal prosecution based on “cyberbullying” on MySpace or making assault and murder threats on Twitter.

In May, authorities in Guatemala arrested and charged a man after he sent a 96-character tweet urging depositors to withdraw funds from a bank involved in a political-murder scandal. As Associated Press reports (via USA Today), the message earned him the dubious distinction of becoming one of the first people ever to be arrested for a tweet.

How Much Trouble Can One Tweet Cause?. These are just the tip of the proverbial iceberg but illustrate that the law develops by analogy, applying to new situations the traditional rules applicable to similar circumstances. It hardly matters that LaRussa’s lawsuit, for instance, was not controlled by the federal statute making fraudulent or bad faith domain name registration unlawful (15 U.S.C. 1125(d)) where the domain infringes a trademark. He was still permitted to bring a lawsuit claiming that Twitter’s “misappropriation” of his name as an Internet identifier violated his rights. That the suit ultimately was dismissed before a decision is far less important than that the issue was raised, for the first time, in the context of a judicial dispute.

All of this suggests informed observers should regard pronouncement of social media law as tentative. The traditional rules applicable to social interactions may apply, or may apply differently, in the context of social media. In other respects, social media may upend traditional notions of legal status and privacy. And with the increasing penetration and popularity of location-based services, which can make one’s physical presence a matter of public record, as well as a commercial commodity, the disruptive impact of social media will likely extend to the law itself.

In Part II of this series of essays, we explore the impact of social media on intellectual property law, focusing on copyright (and then trademark).

This weekend’s events in Iran were stirring, scary and historic. More about the impact of social media and technology later, but for now just look at this near real-time photo posted via TwitPic from Tehran as of Monday afternoon. It has all the qualities to become an iconic image of these protests and what increasingly appears to be evolving before the world’s eyes — not on major television or newspaper media, which are largely repeating posts from the Twittersphere —into either a popular revolution or prelude to a massive and violent crack-down by the clerics.

As Mike Madden writes today in Salon, of course “social media is documenting the Iranian revolution — not leading it.” But that still requires media exposure, coordination and communication, all of which Twitter supplies in spades. No, social media will not bring down Ahmadinejad, the Iranian people can only do that. Imagine if Tom Paine in 1775 or Cory Aquino in 1987 had the one-to-many power of social networking communication instead of pamphlets and radio. Just as “Internet time” speeds up the old world, so too does social media — whether China, Iran or otherwise — provide a new and powerful tool for political revolution.

Posted via email from glenn’s posterous

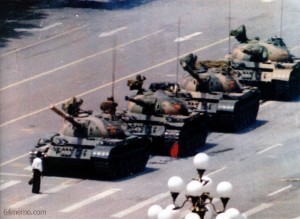

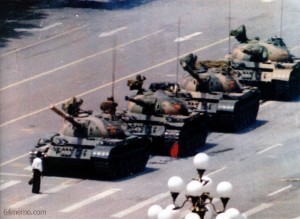

It was 20 years ago today (thanks, John & Paul…) that China sent its military into Tienanmen Square to put down a student-led uprising devoted to inculcating Western democratic values into the PRC. The photos of that young man standing in front of a row of tanks will never lose their place among the most famous images in history.

Tienanmen Square 1990 But imagine if the Tienanmen protests had been coupled with the power of the Internet, especially social media. Just as news is dispersed even quicker on Twitter than Web-powered news sites — which themselves compress the news cycle to hours from days — the immediacy of social media provide a fertile ground for mass gatherings and other grassroots organizing efforts. In the U.S., we can see this with Tweetsgiving and the like, plus MoveOn and other progressive political activists. In the authoritarian parts of our world, however, it is the opposite.

The answer to the imaginary question is that if Twitter and other social media networks had been available in China, Shanghai might already be free, more than economically. One can see this clearly from the reaction of the Chinese party to social media in its preparations to bury anniversary celebrations of the Tienanmen massacre. China Blocks Twitter, Flickr, Bing, YouTube and Hotmail Ahead of Tiananmen Anniversary [guardian.co.uk]. It is hardly different from Iran, for example, which banned Facebook for nearly ten days leading up to its recent elections, or Cuba and other repressive regimes blocking Internet technology and sites in order to control propaganda. But the significance is overwhelmingly real. ”Information wants to be free,” the old watchword of hacking and digital freedom proponents, is alive and well in this Web 2.0 era. Just check out the trending Twitter topic #ChinaBlocksTwitter to see for yourself.

This Mashable headline suggests, as devotees understand viscerally, that the Internet’s current social networking phenomenon is radically changing communications modes on the Net. Not only is email on the way out, but now the very existence of “static” Web sites is being questioned.

This is more than a question of style, I suggest. The real-time, one-to-many nature of social media communications, including the near-instantaneous (and highly personalized) responses generated by Facebook, Twitter and the like, is revolutionizing business. In my legal practice, there are already clients and potential clients who message me almost entirely via social media. Yes, there are risks involved, like privacy, but the time spent on social media sites rewards users by giving them a mode for interaction that is intergrated with their digital lifestyles.

So the answer to Mashable’s question is almost certainly “yes,” as far as brand-protection and CRM are involved. Obviously, Web sites will still be important for software updates, product downloads and the like. But more and more, business interactions with customers and vendors will likely be by status update or “social stream.”

Which raises perhaps an even more important question. Is “social media” plural? If so, the headline should read “Are social media….”

Posted via email from glenn’s posterous

OK, so my new colleague Ryan Wynia at BeYOB.com posted, in bullet form, the “rules of engagement” for social media for businesses I presented at SPARKt2 in Chicago on April 29. Glenn Manishin’s Rules of Engagement [BYOB]. But that short treatment misses some of the nuances, and besides, I thought of them first! So here are my six rules of engagement for social media — Twitter, Facebook, etc.– all of which can be summed up in the phrase “if you are going to do it, do it right.”

1. Be Authentic…Have an Identity. When using social media for business, you must establish a unique identity. While the early Web was accompanied by the slogan “No one knows if you are a dog on the Internet,” social media are different. Reputation and credibility flow from identity. If you want to develop business via social media, don’t be anonymous and do not be a cartoon. Logos may be fine for corporate PR and customer relations postings, but without a profile photograph, bio and link, audiences will be far less likely to follow you and even less willing to believe what you say.

2. Offer Value (Content), Not Self-Promotion. This should be a no-brainer. When participating in social media, what is of interest to other members is substance. Despite popular misconceptions, social networking is not about revealing what one ate for breakfast. Rather, it is providing domain expertise to others by sharing one’s knowledge, experience and insights. Twitter is filled, for instance, with get-rich quick and Web marketing schemes, life coaches, success gurus, MLM schemers and others engaged in overt sales pitches. They are rapidly becoming classified as “Twitter spam” and rightfully ignored. To gain an audience, talk about what you know, not what you sell.

3. Listen to the Audience. A corollary to rule #2, stay sensitive to “trending” topics and engage on matters of relevance to the audience. That means listening as much as talking on social media sites. A traditional maxim for negotiations is that one must acknowledge the views and statements of others (”I hear what you say…“) before responding, especially if critiquing. By engaging after listening, one can ensure that posts and updates reflect the issues on which the audience is looking for information. And by providing it, you can and eventually will gather your own audience of followers and readers.

4. Tone Matters. “Social stream” is rapidly replacing email as a dominant form of digital communication. But even more than email, social presence and status updates are communicated in near real-time, meaning that hitting the “post” or “update” button without thinking about the wording of your content can be disastrous. Mainstream media is filled with stories of employees being disciplined or fired, and applicants rejected, because of inappropriate “Tweets.” This is so way more problematic than a college student uploading drunken beer pong photos to Facebook or Flikr. Sacrcasm reads even worse on social media than it does in email. Avoid flame wars at all costs!

5. Follow, Answer and “Retweet.” The Web is about content and community, not technology. So after adjusting to the immediacy of social streaming, the most important aspect of doing business on social media is engaging that community by participating as a full-fledged member. Lurking is dated and counterproductive. Interact with others, promote good ideas by following and reposting authors. The more you participate the more you can profit in the long run.

6. Remember That “Tweets Live Forever.” Nothing one posts on social media sites goes away, even after one quits. Facebook, for instance, made clear in February that content shared with other members survives if a member cancels his or her subscription. Blog comments, Twitter posts, etc., are archived and indexed by Web bots and spiders almost instantly. You can delete a Tweet, but chances are almost 100% it remains visible to the world. So when posting content, ask the old question–would you want your update to appear on the front page of the New York Times? If the answer is no, trash it and move on. Remember, social media for business is about brand and reputation building. You will never sell anything if your “recalled” updates brand you as a loose cannon or a curmudgeon.

What do you think? Reactions appreciated. You can also check out my companion post on SiliconANGLE.

Two weeks ago there was a major outcry within the Facebook community over revised Terms of Service (ToS) for the hugely popular social networking site. The gist of the protest was an implication in the new ToS that Facebook claimed “ownership” of user-generated content (UGC) and reserved the right to market it for for commercial purposes.

Facebook ToS That conclusion would be rather stupid from a business perspective and was quickly disowned by Facebook management. Facebook CEO Zuckerberg: “We Do Not Own User Data” [Mashable]. But because this was a Website policy, changeable unilaterally without user consent, it leaves unanswered the larger question of whether UGC is owned by the person posting the content, the person on who’s page/site the content appears or the owner of the service/server. The issue is WAY broader than Facebook. It applies, for instance, to comments posted on newspaper sites, blogs, photos shared on Flickr and the like, and many more applications.

Today I am not trying to answer the question, rather raising some. In the law of traditional commercial relationships — say banking or telephony — the “content” one shares with a company is owned by the corporation. Your banking records can be obtained by the government without your consent because they are “owned” by the bank. Only sector-specific privacy laws like Gramm-Leach-Bliley, which are altogether too rare in the United States, limit what the company can go with data arising from its relationship with customers. Hence, Facebook was possibly wrong (although correct from a customer relationship standpoint) to argue that it needed a license from one user to display his/her content on the “Wall” of another user, even when the first person had affirmatively decided to share that UGC by posting it within Facebook.

But what of corporations as employers? Since the law is settled, right or wrong, that a company owns emails generated on its systems, regardless of whether work-related, will that same conclusion hold for social communications sent and received via an enterprise Internet connection? And what of copyright; if a user posts photos to a sharing site, does that act imply either abandonment of their ownership interest or the grant of a “fair use” right to republication in full to the world?

These are interesting, and perhaps important, questions in the developing law of social media. Stay tuned here for more analysis and discussion as we make some tentative predictions of how the law will evolve and whether, in the ultimate analysis, it matters.

Well, this has got to take the cake. The official trade rag of the legal industry — a notorious technology backwater for decades — is publicizing the wonders of the Internet social networking phenomenon Twitter. And that’s not all. More Attorneys Tweet in Twitterverse [ABA Journal]. Of course, being lawyers they take credit for the whole thing:

Attorneys posting such “tweets” on Twitter are credited with helping to drive a massive increase in subscribers this year, from fewer than 300,000 at the end of 2007 to an estimated 3 million-plus by the end of 2008.

Yeah, and the ABA will single-handedly solve global warming and welcome the messiah to Earth. That would apparently be Messiah 2.0 now!

|

|