A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

Three high-level staffers at the Federal Trade Commission (Andy Gavil, Debbie Feinstein and Marty Gaynorare) are backing Tesla Motors Inc. in its ongoing fight to sell electric cars directly to consumers. As we’ve observed, Tesla forgoes traditional auto dealers in favor of its own retail showrooms. But that business model was recently banned by the New Jersey Motor Vehicle Commission — and is under fire in many other states as well — as a measure supposedly to protect consumers.

The ubiquitous state laws in question were originally put into place to prevent big automakers from establishing distribution monopolies that crowd out dealerships, which tend to be locally owned and family run. They were intended to promote market competition, in other words. But the FTC officials say they worry (as have we at DisCo) that the laws have instead become protectionist, walling off new innovation. “FTC staff have commented on similar efforts to bar new rivals and new business models in industries as varied as wine sales, taxis, and health care,” the officials write in their post. “How manufacturers choose to supply their products and services to consumers is just as much a function of competition as what they sell — and competition ultimately provides the best protections for consumers and the best chances for new businesses to develop and succeed. Our point has not been that new methods of sale are necessarily superior to the traditional methods — just that the determination should be made through the competitive process.” The ubiquitous state laws in question were originally put into place to prevent big automakers from establishing distribution monopolies that crowd out dealerships, which tend to be locally owned and family run. They were intended to promote market competition, in other words. But the FTC officials say they worry (as have we at DisCo) that the laws have instead become protectionist, walling off new innovation. “FTC staff have commented on similar efforts to bar new rivals and new business models in industries as varied as wine sales, taxis, and health care,” the officials write in their post. “How manufacturers choose to supply their products and services to consumers is just as much a function of competition as what they sell — and competition ultimately provides the best protections for consumers and the best chances for new businesses to develop and succeed. Our point has not been that new methods of sale are necessarily superior to the traditional methods — just that the determination should be made through the competitive process.”

As Tesla’s CEO Elon Musk noted earlier this year, “the auto dealer franchise laws were originally put in place for a just cause and are now being twisted to an unjust purpose.” Yes, indeed. It is pure rent seeking by obsolescent firms. State and local regulators have eliminated the direct purchasing option by taking steps to shelter existing middlemen from new competition. That’s not at all consumer protection, it is instead economic protectionism for a politically powerful constituency. Thanks to the FTC staff, some brave state legislators may now be emboldened to resist the temptation to decide how consumers should be permitted to buy cars.

Unfortunately, the issue is not limited to automobiles. I wrote recently about how in New York City, officials want to ban Airbnb because its apartment rental sharing service is not in compliance with hotel safety (and taxation) rules. The New York Times last Wednesday editorialized in support of that approach, arguing that Airbnb is reducing the supply of apartments and increasing rents. They’re wrong, of course, because short-term visits obviously do not substitute for years-long apartment leases. But the more important issue is that one economic problem does not justify reducing competition in a separate market. If New York actually has an apartment rent price problem, banning competition for hotels is no more a solution than prohibiting direct-to-consumer auto sales.

Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

Tuesday was a big day in the world of tech-powered disruptive innovation. What the news of April 22nd shows, however, is expanding use of the legal process by incumbent industries to thwart change — and the unfortunately all too frequent concurrence of regulators and courts with that ancient mantra of obsolescent businesses, namely “consumer protection.” Old, entrenched industries frequently lean on their political connections and get the government to come up with some new justification (or recycle an old one) for shutting down upstart rivals or, at the very least, undermining their competitive advantages.

Tuesday witnessed two potentially landmark events, ones that may in time change this familiar paradigm. The first was the morning hearing before the U.S. Supreme Court in ABC v. Aereo, the broadcast networks’ copyright law challenge to the now well-known streaming IPTV start-up. The second, just slightly later in the day, were oral arguments at a New York state court in Albany over whether Airbnb will be permitted to offer its peer-to-peer apartment rental services in New York City, where a 2010 measure meant to curb unregulated hotels prohibits renting out an apartment for less than a month.

The DisCo Project has devoted a series of posts to the Aereo case. Like a Sony Betamax for the 21st century, the Supreme Court is being asked to decide whether moving technology that is lawful for an individual to use on his or her own becomes a copyright violation if offered over the Internet. But the major broadcast networks (like the movie studios who opposed VCR recording in the 1980s) are convinced their entire business model will collapse if Aereo is sanctioned, threatening the nuclear option of stopping over-the-air transmission in favor of all-cable distribution should Aereo prevail.

Airbnb, in contrast, is fighting an effort by New York regulators to collect the names of Airbnb hosts who are breaking the law by renting out multiple properties for short periods. The company, which is now estimated to be worth $10 billion, is framing the dispute as a case of government scooping up more data than it needs for purposes that are vague. What the tussle is really about, of course, is whether the renting public actually needs protection from “unregulated hotels” and, even if true, why Airbnb’s efforts to make a market for DIY rentals is at all harmful. Continue reading Tech Tuesday: Litigation, Legislation and Regulatory Protectionism

The strangely named Rockstar Consortium has been in the news again, in part because some of its members just formed a new lobbying group, the Partnership for American Innovation, aimed at preventing the current political furor over patent trolls from bleeding into a general overhaul of the U.S. patent system. Yet Rockstar is perhaps the most aggressive patent troll out there today. Hence the mounting pressure in Washington, DC for the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division — which signed off on the initial formation of Rockstar two years ago — to open up a formal probe into the consortium’s patent assertion activities directed against rival tech firms, principally Google, Samsung and other Android device manufacturers.

Usually the fatal defect in antitrust claims of horizontal collusion is proving that competing firms acted in parallel fashion from mutual agreement rather than independent business judgment. In the case of Rockstar — a joint venture among nearly all smartphone platform providers except Google — that problem is not present because the entity itself exists only by agreement among its owner firms. The question for U.S. antitrust enforcers is thus the traditional substantive inquiry, under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, whether Rockstar’s conduct is unreasonably restrictive of competition.

Despite its cocky moniker, Rockstar is simply a corporate patent troll hatched by Google’s rivals, who collectively spent $4.5 billion ($2.5 billion from Apple alone) in 2012 to buy a trove of wireless-related patents out of bankruptcy from Nortel, the long-defunct Canadian telecom company. It is engaged in a zero-sum game of gotcha against the Android ecosystem. As Brian Kahin explained presciently on DisCo then, Rockstar is not about making money, it’s about raising costs for rivals — making strategic use of the patent system’s problems for competitive advantage. Creating or collaborating with trolls is a new game known as privateering, which allows big producing companies to do indirectly what they cannot do directly for fear of exposure to expensive counterclaims. Essentially, it’s patent trolling gone corporate. As another pro-patent lobbying group said at the time, Rockstar represents “a perfect example of a ‘patent troll’ — they bought the patents they did not invent and do not practice; and they bought it for litigation.” Predictiv’s Jonathan Low put it quite well in his The Lowdown blog:

The Rockstar consortium, perhaps more appropriately titled “crawled out from under a rock,” is using classic patent troll tactics since their own technologies and marketing strategies have fallen short in the face of the Android emergence as a global power. Those tactics are to buy patents in hopes of finding cause, however flimsy, to charge others for alleged violations of patents bought for this purpose. Rockstar calls this “privateering” in order to distance itself from the stench of patent trolling, but there are no discernible differences.

Continue reading Rockstar’s Patent Trolling Conspiracy

Google’s competitors “are locked in hand-to-hand combat with Google around the world and have the mistaken belief that criticizing us will influence the outcome in other jurisdictions.”

The coalition of companies that for years has unsuccessfully been pressing antitrust complaints against Google for search “abuse” — FairSearch.org — insists Google must be restrained for fear the Mountain View company will steer search users to its commercial products, like flight bookings. The group’s most recent publicity event, held at the ABA’s Antitrust Section annual spring meeting last week, repeated those same claims. FairSearch ventured as well into new ground, attacking what it terms Google’s unreasonably restrictive Android licensing practices.

There are four straightforward reasons FairSearch is wrong.

1. Predictions of Foreclosure Have Proven Totally Baseless.

When Google purchased travel software maker ITA in 2011, FairSearch maintained that Google would exploit its control over the ITA tools that power other online travel agencies, along with many of the airlines’ own sites, to usher competing search services off the stage, then jack up ad rates for travel queries and favor flights from particular airlines.  Three years later, nothing like that has happened. In fact, Google Flight Search is not among the top 100 or even the top 200 travel listing sites. Rather, it’s in 244th place, behind Hipmunk, with just .04% of travel queries. Real-world experience, in other words, reveals that the predicted competitive risks on which FairSearch bases its advocacy are both hypothetical and fanciful. Continue reading Four Reasons Fairsearch Is Wrong Three years later, nothing like that has happened. In fact, Google Flight Search is not among the top 100 or even the top 200 travel listing sites. Rather, it’s in 244th place, behind Hipmunk, with just .04% of travel queries. Real-world experience, in other words, reveals that the predicted competitive risks on which FairSearch bases its advocacy are both hypothetical and fanciful. Continue reading Four Reasons Fairsearch Is Wrong

My Troutman Sanders colleagues have written before on the continuing judicial wrangling over whether GPS tracking devices, as well as location data maintained by wireless telecom providers, require a warrant before search and seizure by the government. Last July, a New York state court ruled that a government employer did not need a warrant to attach a GPS device to an employee’s car and monitor his movements continuously for a month, contradicting an earlier decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court. More recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held — after a thorough review of precedent dating all the way back to 1981 — that law enforcement agents must indeed first obtain a warrant based on probable cause to attach a GPS device to a criminal suspect’s vehicle.

Cases dealing with this issue merit watching because they represent the “front lines” of the intersection between personal privacy and technological capability. The Supreme Court in United States v. Jones, 131 S. Ct. 3064 (2011), decided that GPS tracking generally requires a warrant,  but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider. but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider.

So what does all this mean for the business community? Although law enforcement and the rather esoteric realm of constitutional law has been at the front lines of GPS privacy, there are a number of developments indicating that location privacy is also an important business issue:

First, the Federal Trade Commission — which functions as the de facto privacy regulator in the United States — has launched an inquiry into GPS tracking with a seminar convened on February 19 in Washington, D.C. This followed an FTC staff report last year, titled Mobile Privacy Disclosures: Building Trust Through Transparency, which “recommended” that companies consider offering a Do Not Track (DNT) mechanism for smartphone users among other measures to protect location privacy. Since the FTC has authority over unfair trade practices, including privacy, in almost every industry other than telecommunications, this initiative portends a risk of administrative sanction for private businesses not offering consumer choice as part of location-based services.

Second, HTC and Samsung smartphones come pre-loaded with software from the company Carrier IQ. More than 100 lawsuits filed since 2011 in federal court claim the phones unlawfully track the keystrokes of text messages and Internet searches. While the company maintains that the data are collected for customer support and to help troubleshoot network problems, it has become embroiled in litigation despite serving only as a technology vendor to other, far larger firms. (Not to leave them out, both Microsoft and Apple have also been sued over the location tracking features of their phones.) The lesson of Carrier IQ is that businesses are at risk in the GPS space even where they are not consumer-facing enterprises.

Third, a number of start-ups (Turnstyle, RetailNext, Nomi, shopkick, etc.) offer brick-and-mortar retailers the ability to use indoor location sensors and security video feeds to track movements of shoppers, recreating in the retail realm the same in-depth data on customer behavior that online merchants have long collected. Some of these firms follow best-practices by obtaining explicit opt-in for location information sharing. But the potential for adverse consumer reaction, and class action litigation, remains high ever since Nordstroms was caught in a PR whirlwind in July and unilaterally discontinued its in-store location program after notifying shoppers they were being tracked.

Fourth, it matters not whether a company is actually in the business of commercializing GPS data. In December, the FTC settled with the makers of an Android flashlight app after the agency claimed the company’s privacy policy was deceiving users into sharing their location and personal information with third-party advertisers. So there is still legal exposure for location information collection even if a firm operates in a completely different space.

Legal maneuvering can, at least for now, offset some of these risks. Under the current rules governing consumer class actions, several courts have decreed that privacy injury is insufficiently direct and substantial economically to support standing or to qualify for class action certification in federal court. For instance, in a case challenging a mobile app’s collection of geo-location data without consent, Goodman v. HTC America, Inc., the Western District of Washington held that the putative class members had not sufficiently plead injury to have standing. The court accepted as cognizable injuries overpayment for phones (because the plaintiffs would have paid less if they knew their location was to be collected as alleged) and diminution in value of the phones because of reduced battery life caused by the collection of geo-location data. Still, the court concluded that the “assertion that defendants misappropriated their personal information is not a sufficiently particularized injury to support [plaintiffs’] standing.” Yet since this opinion, and others from similar cases, holds out the possibility that identity theft or other financial harm may in the future result from insecure information collection, the standing defense appears to be time-limited.

The 4th Amendment protects people only from overreaching by the government. That may have led some in the business community to conclude prematurely that GPS and location tracking are issues only of concern to hackers and criminal enterprises. As these four developments show, however, location privacy is a serious business issue too.

Note: Originally written for and reposted with permission of my law firm’s Information Intersection blog.

Thirteen months after the U.S. Federal Trade Commission settled its antitrust investigation of Google Inc. by flatly declining to regulate the company’s search practices, the European Union is poised to do just that. This development highlights a serious rift between the two most influential competition authorities worldwide — and their very different value systems.

It has been true for years that on important Internet policy issues such as privacy, defamation, censorship and government surveillance, the 30-member EU has adopted principles far more intrusive for businesses, and likewise more protective of consumers, than in the U.S. Similarly, ever since a proposed General Electric-Honeywell merger was scuttled by the European Commission’s competition directorate in 2000, there have been a few highly visible cases in which the EU’s view of antitrust as a basis for protection of smaller entities in the marketplace has produced sharply different results.

So it is hardly surprising that EU Competition Commissioner Joaquin Almunia announced recently that several expanded concessions offered by Google to resolve his concerns about the fairness of the company’s search practices — which would fundamentally alter search by requiring Google to display links to rival search competitors on results pages served to its own search users — had finally borne fruit. The most basic competition issue asserted by the European authorities was that Google gives preference to its own services, like travel search, by placing those “specialised” (in European spelling) results above “organic” or natural search results. Google proposes to label these specialized results as paid placements and to add prominent links to rivals alongside. Despite vocal complaints by Google’s so-called vertical competitors that these substantial changes in search display — putting Expedia travel link results, for instance, on the same level of visibility as Google’s own sponsored links — still do not meet their needs, the fact that the EU is using its power to force serious search engine revisions on Google represents a watershed moment illustrating how far apart the two systems were and can still be at times.

There are three principal ways in which the inconsistent U.S. and EU Google settlements epitomize this continuing war of the worlds over antitrust enforcement:

- Is Google a Bottleneck “Gateway”? Almunia’s investigation was overtly premised on the concept that Google’s 90 percent share of Web searches in Europe (compared to some 70 percent in the U.S.), equals monopoly power as a gateway essential to success for Internet businesses. American jurisprudence, in contrast, has largely abandoned the bottleneck classification and its corollary, the “essential facilities” doctrine. Moreover, U.S. competition enforcers and courts distinguish between consumer preferences (which are changeable) and a dominant’s firm’s economic power (which can persist for long only when sheltered by entry barriers) in a way that contradicts the EU premise. As one federal court explained in January, the “ability to act as a ‘gatekeeper’ distinguishes broadband providers from other participants in the Internet marketplace — including prominent and potentially powerful edge providers such as Google and Apple — who have no similar control over access to the Internet for their subscribers and for anyone wishing to reach those subscribers.”

- Is Consumer Deception an Antitrust Issue? The EU has been focused, in large part, on the fact that when redesigning its search result displays, Google may have confused Internet users by not specifically indicating that some results are now based not on generic search algorithms, but instead a decision to integrate links to Google’s own services on results pages. Almunia believes that the potential for misleading consumers justifies a competition remedy, saying that Google must “signal what are the relevant options, alternative options, in the way they present the results.” In contrast, American antitrust law is clear that fraud, deceptive advertising and other commercial bad acts alone are not of competitive concern. Consumer protection remains important in the U.S., but our legal principles separate regulation of consumer issues from the competition-preservation function of antitrust policy.

- Should Antitrust Protect Traffic to Google’s Competitors? By far the biggest difference in the EU approach to competition enforcement is the historical European preference for domestic firms in established industries. In France, for instance, Internet publishers pay a tax that subsidizes newspapers and printed mapmakers, something anathema to the American idea of a free market. Where Google is concerned, the question becomes whether, as an important source of Web traffic for competing specialized search services, its practices should be regulated in order to guarantee hits to rival sites. The EU has been somewhat schizophrenic, at first condemning what it termed “diversion of traffic” to Google itself and characterizing its mission as to “guarantee that search results have the highest possible quality,” then later stressing that its “aim is not to artificially send traffic to sites that compete with Google.” The bottom line, however, is that by seeking to stop Google from “diverting” Internet search users from the complaining sites, the EU is in part attempting to dictate the results of competition, something American antitrust leaves to the marketplace.

Yes, these differences can sometimes be overstated. Both the EU and American antitrust agencies mutually believe that competitive markets produce the best outcomes and that, absent abuse by firms with monopoly power, the government should not try to pick winners and losers. The contrasting values typically appear only in hard cases, where the facts are ambiguous or the competitive consequences difficult to predict. Different enforcement decisions in Europe and the U.S. are uncommon, but when they do occur, are important as more than isolated instances.

There is a ray of light in all of this, one conclusion on which both Almunia and Jon Leibowitz, the former FTC Chairman who closed the U.S. government’s investigation of Google last year, agree wholeheartedly. Neither the EU nor the FTC accepts the premise of complaining search competitors that antitrust law embraces a concept they term “search neutrality,” namely that search providers must treat all queries and results under the same objective standard. The FTC said it had neither the desire nor institutional expertise to “regulate the intricacies of Google’s search engine algorithm.” The EU likewise concluded that its Google remedies should address “the way they present their own services” rather than “discussing the algorithm” used for Internet search.

This is one way, unlike the Martian invaders in the H.G. Wells novel, that the shared histories of America and Europe give the developed world a sustainable advantage in economic performance. On both the continent and in the New World, new business ideas succeed if they are better designed to meet the needs of consumers. With rare exceptions, we do not intervene in the marketplace to achieve government-desired competition results or to exclude some firms for political or social reasons. That is particularly key to the different Google search remedy approaches. Since everyone admits Google got to its present position by building a better search engine, the consequences of allowing competition policy to morph into an artificial tool of technology regulation by way of search neutrality are enforcement quicksand for the government, regardless of which “side of the pond” it sits.

Every new year sees a slew of top 5 and top 10 lists looking backwards. Here’s one that looks forward, predicting the five biggest disruptive technologies and threatened industries for 2014.

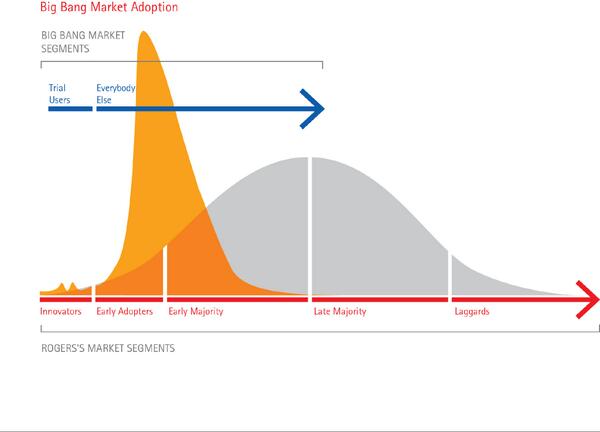

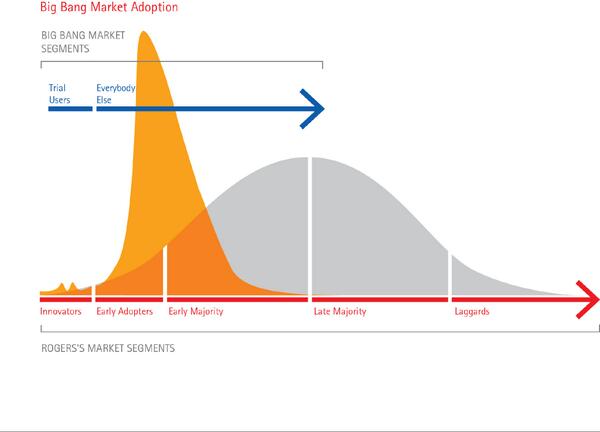

Making projections like these is really hard. Brilliant pundit Larry Downes titles his new book (co-authored with Paul Nunes) Big Bang Disruption: Strategy In an Age of Devastating Innovation. Its thesis is that with the advent of digital technology, entire product lines — indeed whole markets — can be rapidly obliterated as customers defect en masse and flock to a product that is better, cheaper, quicker, smaller, more personalized and convenient all at once.

Since adoption is increasingly all-at-once or never, saturation is reached much sooner in the life of a successful new product. So even those who launch these “Big Bang Disruptors” — new products and services that enter the market better and cheaper than established products seemingly overnight — need to prepare to scale down just as quickly as they scaled up, ready with their next disruptor (or to exit the market and take their assets to another industry).

Disruptors can come out of nowhere and happen so quickly and on such a large scale that it is hard to predict or defend against. “Sustainable advantage” is a concept alien to today’s technology markets. The reputation of the enterprise, aggregated customer bases, low-cost supply chains, access to capital and the like — all things that once gave an edge to incumbents — largely no longer exist or are equally available to far smaller upstarts. That’s extremely unsettling for business leaders because their function is no longer managing the present but inventing the future…all the time.

I certainly have no crystal ball. Yet just as makers of stand-alone vehicle GPS navigation devices were overwhelmed in 2013, suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere, by smartphone maps-app software, e.g., Google Maps, etc., so too do these iconic industries and services face a very real and immediate threat of big bang disruption this year.

Continue reading 5 Industries Facing Disruption In 2014

Despite the failures in recent years of such well-known retail chains as Circuit City, Borders and the like, it is way too soon to declare that the Internet will replace brick-and-mortar retailing. In part that is because consumer research suggests that in some segments, such as clothing, feeling and touching merchandise is an important part of the buying experience. Of interest to students of technological disruption, retailers are beginning in earnest to deploy technologies marrying the best aspects of online retailing with shopping malls and physical stores.

Delivery is one area where online retailers remain at a disadvantage. Amazon counters with its Prime membership for free two-day delivery, Amazon Lockers for local pick-up and its experimental foray into drone deliveries. Startups like Deliv (described as “a crowdsourced same-day delivery service for large national multichannel retailers”) are now providing equivalently fast store or home delivery for both online and in-person purchases.

Four of the nation’s largest mall operators are turning their properties into mini-distribution centers for rapid delivery, meaning shoppers can ditch their bags and keep spending. The service promises set delivery times for purchases consumers make at the mall or online from mall tenants, facilitated by a Silicon Valley start-up, Deliv Inc….The move highlights how delivery has become a key battleground in the war between physical and online retailers.

Startup Offers Same-Day Delivery at Shopping Malls | WSJ.com.

That in itself is remarkable. It shows that disruption is not a one-way street for legacy retailers. Yes, theirs is a challenging business environment, but technology is beginning to supply features for physical stores that meet and in some cases can beat online shopping providers. Home Depot, for instance, offers a smartphone app that allows consumers to check store inventory and aisle location, scan QR and UPC codes to get more information about products and order online with in-store delivery, overcoming some of the chain’s long-standing weaknesses: confusing layouts, out-of-stock merchandise and resulting abandoned visits.

Perhaps the most controversial realm is that of in-store consumer tracking and special offer distribution. This made news just last week when Apple Inc. turned on its iOS7 “iBeacon” service at its own retail stores. Macy’s has activated a shopkick-powered service through which simply walking into a Macy’s location will automatically send specialized offers to customers depending on where they are in the store. As Wired observed:

That’s just the beginning, though. Retailers are already talking about things like in-store navigation and dynamic pricing, all made possible by beacon-enhanced retail locations. For independent shops, iBeacon is a chance to jump into the smartphone era with one fell swoop. A $100 beacon is all it takes for even the mustiest book store to track customers, make recommendations, and offer discounts to customers’ pockets.

The risk, however, is that consumers may reject secret tracking technologies that retailers use internally, absent notice and consent. Over the last two years, retailers such as Nordstrom have hired software firms that gather Wi-Fi and Bluetooth signals emitted from smartphones to monitor shoppers’ movements around stores. They use the data to study things like wait times at the check-out line and how many people who browse actually make a purchase. At the prompting of Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) and the Washington, DC-based advocacy group Future of Privacy Forum, several location-tracking firms agreed in October to a code of conduct under which they will ask retailers to post signs in “conspicuous” spots in stores which inform consumers that their movements are being monitored and direct them to a website where they can opt-out. As Kashmir Hill noted in Forbes:

As with many novel and unexpected uses of technology, people have tended to be creeped out by the practice when they learn about it. Ask Path, which was tracking shoppers in malls (in 2011). Or Nordstrom, which came under fire earlier this year for tracking its shoppers without clear notice. Or London, which was using trash bins to collect info from passerbys’ mobile devices.

The flip side is that by offering recommendations and deals with an opt-in policy, retailers could dramatically bridge the divide between the online and brick-and-mortar experiences, making the latter still more like the former. Few consumers react negatively to Amazon or Netflix offering recommended products based on their past purchases. By doing the same thing in real-time, when a shopper passes the relevant store aisle or section, physical retailers would be in a position to offer something no e-commerce site can match: customized shopping with the ability to see, feel and take home impulse purchases enabled by technology.

There remain a slew of legal questions about whether the data collected by location-technology providers and retailers qualifies as personally identifiable data subject to the European Union Privacy Directive and the corresponding EU Safe Harbor in the U.S. In this country, it seems likely that the unique phone IDs associated with wireless devices — which are only linked to subscribers in the carrier’s switching and billing systems — would not be considered personal data by the Federal Trade Commission. In Europe, countries like the Netherlands and France have already articulated a more expansive view which could encompass device information in addition to name, address, phone numbers and the like. But even in the more liberal America, some have questioned whether retailers will be forced, whether by consumers or regulators, to dial-back autonomous tracking and adopt more transparent location practices.

All of this brings back memories for me personally. Nearly 15 years ago, I represented a start-up that was developing GPS chips for smartphones. While they are now ubiquitous (the start-up was sold to Qualcomm in March 2000), the challenges in making GPS work without a dedicated, external antenna were substantial. So like any good disruptor, my client went to the Federal Communications Commission to advocate cell phone location rules for E911 service that could give it a competitive advantage in the marketplace. The anecdote we used in our lobbying was that McDonald’s could message your phone, when passing one of its outlets, asking “Have you had your break today?” (That certainly dates the message, of course).

Technology has evolved so much that shopping is now almost at that place. Location tracking platform providers and their retail clients are offering a degree of interactivity never before available at retail. Whether it is compelling or creepy to consumers, of course, remains to be determined.

Note: The author has represented shopkick Inc., but not in connection with the company’s privacy policies and practices. Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

As a recent story from the The Washington Post illustrates well, “tradition” is a gating factor in the ongoing transformation of the legal industry. Despite the highly conservative nature of courts, bar associations and attorneys, however, in the post-Great Recession legal market of 2013, technology and changing values are rapidly disrupting traditional legal services.

My colleague and friend Jonathan Askin, Founder of the Brooklyn Law Incubator & Policy Clinic, hosted a seminar on legal start-ups in late August. Many of the companies highlighted there are focused on low-hanging fruit, taking the trend started by LegalZoom of moving do-it-yourself work product to consumers into spaces that for decades have remained buttoned-up by prohibitions against “unauthorized practice of law” and the resistance of lawyers to allowing clients document control. (LegalZoom itself has been challenged by bar groups and class action plaintiffs in North Carolina, Connecticut, Missouri and California for allegedly engaging in the practice of law, a classic and anticompetitive use of regulations designed to protect consumers, not prohibit new business models.) Like taxi-hailing companies Uber and Sidecar, legal start-ups thus face opposition from incumbents who are well-situated to employ archaic regulatory regimes to thwart new entry.

Nonetheless, the four emerging firms Askin profiled make a persuasive case that the guild-like barriers which for centuries protected lawyers from competition are breaking down before our eyes.

- Shake allows consumers to create binding contracts automatically on their smartphones or tablets with a few Q&As and then sign them electronically.

- Lawdingo leverages the power of networking to connect consumers to lawyers for real-time quick (and often free) answers on a virtually unlimited number of topics.

- Caserails offers cloud-based document assembly and editing functionalities for individuals or groups, long the bane of corporate transactions.

- Priori Legal allows SMBs to select among a trusted community of lawyers for discounted or fixed-rate engagements with Web-based comparison shopping.

The best and brightest of these firms will undoubtedly rise to the top over time. Much like banks in the 1970s — when toasters as deposit “gifts” were replaced by deregulated interest rates and tellers by ATMs — legal consumers no longer care or very much appreciate the old traditions of the legal profession, especially its convoluted language, fancy office space and expensive artwork. The successful start-ups in this steady disintermediation of legal services will be the ones who recognize that they are driven by what legal transactions can and will be, not what they have been historically, and that they are technology companies solving legal problems, not legal companies trying to understand technology. Continue reading Disrupting the Legal Industry

Are copyright holders allowed to decide without legal constraint to whom they will license their content and on what terms? That is the issue facing Pandora and other new streaming radio firms, for whom music and its associated licensing fees represent the biggest hurdle to commercial success against more established broadcast radio competitors. The answer lies in the sometimes obscure interface between the Copyright Act and antitrust law in the U.S.

In Pandora Media, Inc. v. American Society of Composers, Authors & Publishers, an antitrust case currently pending in federal court in New York, the streaming company is suing ASCAP and some of the major record labels for “withdrawing” their content from the ASCAP joint licensing venture, thus forcing individualized negotiations. It’s a leading-edge dispute, scheduled for trial by year-end, that may help catalyze a new approach to the old question of whether — and if so to what extent — owners of copyrighted digital content are permitted to refuse to deal with competing distribution channels on dramatically different commercial terms.

Most Project DisCo readers likely know about Pandora, a prominent start-up in the Internet radio space — one of the hottest markets around these days, especially given the launch of iTunes Radio by Apple. What is less understood is that streaming music on the ‘Net is fraught with legal issues surrounding copyright, constraints that effectively function as a barrier to the more widespread adoption of such disruptive technologies.

That’s not a lot different from the case of streaming Internet television pioneer Aereo, which as Ali Sternburg points out is caught in legal limbo between different rules (from conflicting judicial decisions) in different regions of the county: and a whopping legal defense bill as well. Copyright in addition plays a key role in the current exemption of traditional over-the-air radio stations from licensing music, an implicit subsidy the recording industry has been lobbying to change for years.

The Pandora-ASCAP fight represents a tricky issue at the intersection of intellectual property (IP) and antitrust. The ASCAP litigation actually dates to 1941, when the government entered into a consent decree settling a complaint that alleged monopolization of performance rights licenses. The settlement, still in place more than 60 years later, requires the organization to license “all of the works in the ASCAP repertory.” A month ago, presiding District Judge Denise Cote (who also issued the decision finding Apple’s e-book pricing deals a violation of the antitrust laws) entered summary judgment for Pandora. She reasoned that the consent decree gave Pandora the legal right to a blanket license

even though certain music publishers beginning in January 2013 have purported to withdraw from ASCAP the right to license their compositions to “New Media” services such as Pandora. Because the language of the consent decree unambiguously requires ASCAP to provide Pandora with a license to perform all of the works in its repertory, and because ASCAP retains the works of “withdrawing” publishers in its repertory even if it purports to lack the right to license them to a subclass of New Media entities, [Pandora must prevail].

Continue reading Opening Pandora’s Box: Copyright and Antitrust

|

|

The ubiquitous state laws in question were originally put into place to prevent big automakers from establishing distribution monopolies that crowd out dealerships, which tend to be locally owned and family run. They were intended to promote market competition, in other words. But the FTC officials say they worry (as have we at DisCo) that the laws have instead become protectionist, walling off new innovation. “FTC staff have commented on similar efforts to bar new rivals and new business models in industries as varied as wine sales, taxis, and health care,” the officials write in their post. “How manufacturers choose to supply their products and services to consumers is just as much a function of competition as what they sell — and competition ultimately provides the best protections for consumers and the best chances for new businesses to develop and succeed. Our point has not been that new methods of sale are necessarily superior to the traditional methods — just that the determination should be made through the competitive process.”

The ubiquitous state laws in question were originally put into place to prevent big automakers from establishing distribution monopolies that crowd out dealerships, which tend to be locally owned and family run. They were intended to promote market competition, in other words. But the FTC officials say they worry (as have we at DisCo) that the laws have instead become protectionist, walling off new innovation. “FTC staff have commented on similar efforts to bar new rivals and new business models in industries as varied as wine sales, taxis, and health care,” the officials write in their post. “How manufacturers choose to supply their products and services to consumers is just as much a function of competition as what they sell — and competition ultimately provides the best protections for consumers and the best chances for new businesses to develop and succeed. Our point has not been that new methods of sale are necessarily superior to the traditional methods — just that the determination should be made through the competitive process.”

Three years later,

Three years later,