With the controversy surrounding the International Telecommunications Union (a UN treaty organization) just recently subsiding, it is time to take a look at Internet governance from a different perspective. We all know that laws and legal principles differ among countries. What many do not realize is that these laws — most completely non-tech oriented — are having a massive and negative impact on Internet innovation.

In America we proudly have the First Amendment, the fair use doctrine and the DMCA. The first limits the reach of liability for libel (defamation) at least to cases, for non-celebrities, where a publisher is at fault (i.e., negligent). Section 230 of the last allows ISPs, websites and Internet hosts a legal safe harbor from copyright and other legal offenses resulting from user-generated content or any other content that a customer, client or some third-party has published. These landmark legal regimes are hallowed in the U.S., for instance used to strike down overreaching Web censorship efforts by federal government. Fair use, in turn, permits non-commercial or transformative use of a portion of copyrighted content. Think Google image search thumbnails or blockquotes from a news source in someone’s blog or a movie clip in a televised review.

Things are very different elsewhere. Three cases in point.

- In Germany and perhaps soon other EU nations, search engines that display snippets of indexed Web pages in response to user queries are now by statute responsible for paying copyright royalties to the original publisher, regardless of whether the content owner charges for its stories with a paywall.

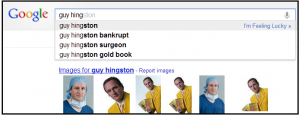

- In France, Italy, Ireland, Australia and now Japan, courts permit individuals to recover for libel based on autocomplete and search results that return incorrect or harmful personal information, but against the search provider, not the writer or content publisher.

- A Denmark court ruled deep linking illegal, as did Germany, leading some to believe that linking to a website other than the front page was illegal throughout Europe. While the German courts overturned that decision, it was Agence France Presse (AFP) which eventually sued Google News for brazenly daring to send search traffic to the organization’s news articles.

These results are foreign, literally, to U.S. jurisprudence. But they also illustrate a vitally important point. Legal regimes that have nothing to do with the Web are being applied in ways which upset existing services users take for granted and that threaten to impede future innovation. Linking is inherent in HTML and represents the essence of the Web. No one in America would argue seriously today that a hypertext URL link represents copyright violation. Search “autocomplete,” in turn, is not a creative activity, but a very useful technical advancement; it applies computer algorithms based on past searches to predict what the current user wants to see, speeding the retrieval of information from the Web.

These results are foreign, literally, to U.S. jurisprudence. But they also illustrate a vitally important point. Legal regimes that have nothing to do with the Web are being applied in ways which upset existing services users take for granted and that threaten to impede future innovation. Linking is inherent in HTML and represents the essence of the Web. No one in America would argue seriously today that a hypertext URL link represents copyright violation. Search “autocomplete,” in turn, is not a creative activity, but a very useful technical advancement; it applies computer algorithms based on past searches to predict what the current user wants to see, speeding the retrieval of information from the Web.

Permitting autocomplete defamation suits against Google or Bing because other Web users have searched for information that damages an individual’s reputation is alien to our American way of thinking. It’s censoring completely accurate factual information about stuff on the Web, although that stuff may itself be factually wrong. The augmentation of liability is also just plain silly, because both autocomplete queries and search results themselves merely return an indexed link to something someone else has posted on the Web.

Continue reading Defamation, Autocomplete And Search Royalties: How Not To Govern the Internet