A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

My Troutman Sanders colleagues have written before on the continuing judicial wrangling over whether GPS tracking devices, as well as location data maintained by wireless telecom providers, require a warrant before search and seizure by the government. Last July, a New York state court ruled that a government employer did not need a warrant to attach a GPS device to an employee’s car and monitor his movements continuously for a month, contradicting an earlier decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court. More recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held — after a thorough review of precedent dating all the way back to 1981 — that law enforcement agents must indeed first obtain a warrant based on probable cause to attach a GPS device to a criminal suspect’s vehicle.

Cases dealing with this issue merit watching because they represent the “front lines” of the intersection between personal privacy and technological capability. The Supreme Court in United States v. Jones, 131 S. Ct. 3064 (2011), decided that GPS tracking generally requires a warrant,  but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider. but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider.

So what does all this mean for the business community? Although law enforcement and the rather esoteric realm of constitutional law has been at the front lines of GPS privacy, there are a number of developments indicating that location privacy is also an important business issue:

First, the Federal Trade Commission — which functions as the de facto privacy regulator in the United States — has launched an inquiry into GPS tracking with a seminar convened on February 19 in Washington, D.C. This followed an FTC staff report last year, titled Mobile Privacy Disclosures: Building Trust Through Transparency, which “recommended” that companies consider offering a Do Not Track (DNT) mechanism for smartphone users among other measures to protect location privacy. Since the FTC has authority over unfair trade practices, including privacy, in almost every industry other than telecommunications, this initiative portends a risk of administrative sanction for private businesses not offering consumer choice as part of location-based services.

Second, HTC and Samsung smartphones come pre-loaded with software from the company Carrier IQ. More than 100 lawsuits filed since 2011 in federal court claim the phones unlawfully track the keystrokes of text messages and Internet searches. While the company maintains that the data are collected for customer support and to help troubleshoot network problems, it has become embroiled in litigation despite serving only as a technology vendor to other, far larger firms. (Not to leave them out, both Microsoft and Apple have also been sued over the location tracking features of their phones.) The lesson of Carrier IQ is that businesses are at risk in the GPS space even where they are not consumer-facing enterprises.

Third, a number of start-ups (Turnstyle, RetailNext, Nomi, shopkick, etc.) offer brick-and-mortar retailers the ability to use indoor location sensors and security video feeds to track movements of shoppers, recreating in the retail realm the same in-depth data on customer behavior that online merchants have long collected. Some of these firms follow best-practices by obtaining explicit opt-in for location information sharing. But the potential for adverse consumer reaction, and class action litigation, remains high ever since Nordstroms was caught in a PR whirlwind in July and unilaterally discontinued its in-store location program after notifying shoppers they were being tracked.

Fourth, it matters not whether a company is actually in the business of commercializing GPS data. In December, the FTC settled with the makers of an Android flashlight app after the agency claimed the company’s privacy policy was deceiving users into sharing their location and personal information with third-party advertisers. So there is still legal exposure for location information collection even if a firm operates in a completely different space.

Legal maneuvering can, at least for now, offset some of these risks. Under the current rules governing consumer class actions, several courts have decreed that privacy injury is insufficiently direct and substantial economically to support standing or to qualify for class action certification in federal court. For instance, in a case challenging a mobile app’s collection of geo-location data without consent, Goodman v. HTC America, Inc., the Western District of Washington held that the putative class members had not sufficiently plead injury to have standing. The court accepted as cognizable injuries overpayment for phones (because the plaintiffs would have paid less if they knew their location was to be collected as alleged) and diminution in value of the phones because of reduced battery life caused by the collection of geo-location data. Still, the court concluded that the “assertion that defendants misappropriated their personal information is not a sufficiently particularized injury to support [plaintiffs’] standing.” Yet since this opinion, and others from similar cases, holds out the possibility that identity theft or other financial harm may in the future result from insecure information collection, the standing defense appears to be time-limited.

The 4th Amendment protects people only from overreaching by the government. That may have led some in the business community to conclude prematurely that GPS and location tracking are issues only of concern to hackers and criminal enterprises. As these four developments show, however, location privacy is a serious business issue too.

Note: Originally written for and reposted with permission of my law firm’s Information Intersection blog.

When is a prediction not worth relying upon? For purposes of analyzing mergers under the Clayton Antitrust Act, a recent decision in favor of the Justice Department indicates that predictions are worth less — perhaps are even worthless — when they are contradicted by the actual facts of the marketplace. The government’s successful legal challenge a couple of weeks ago to the merger of two Internet start-ups ironically shows that the force of predictive judgments remains powerful, even when courts could employ reality as a basis for accurate comparison.

Some background. A 2013 DisCo post authored by the undersigned contrasted “future markets,” where the contours of products and entry do not yet exist and cannot reliably be predicted, with “nascent markets,” in which those features indeed exist but only in their infancy. My thesis was that antitrust enforcement in the latter is preferable because looking back at nascent markets once they have a chance to develop gives the government a more accurate basis on which to assess the actual impact of mergers and concentration than rank projections in which policymakers have no comparative expertise.

The case used to illustrate this theme was United States v. Bazaarvoice, Inc., in which the Justice Department sued to unwind a 2012 merger, already completed, between two firms in what it called the online ratings and reviews platform market. I concluded that

by challenging the merger post-consummation, DOJ has avoided basing its enforcement decisions on predictions of future markets and instead the case should rise or fall on the accuracy of its ex post analysis of actual competitive effects.

That’s not at all what happened, though.

Continue reading Is Bazaarvoice Bizarre?

Every new year sees a slew of top 5 and top 10 lists looking backwards. Here’s one that looks forward, predicting the five biggest disruptive technologies and threatened industries for 2014.

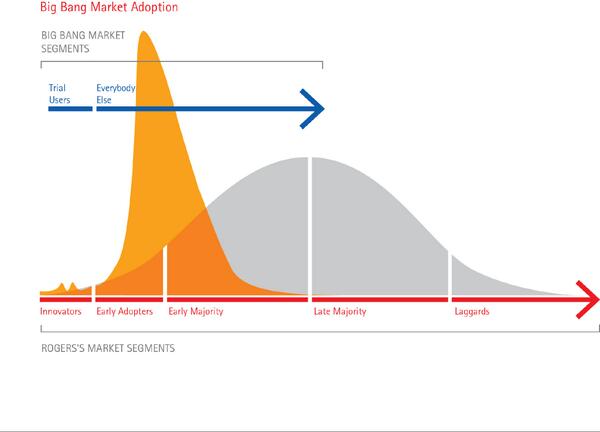

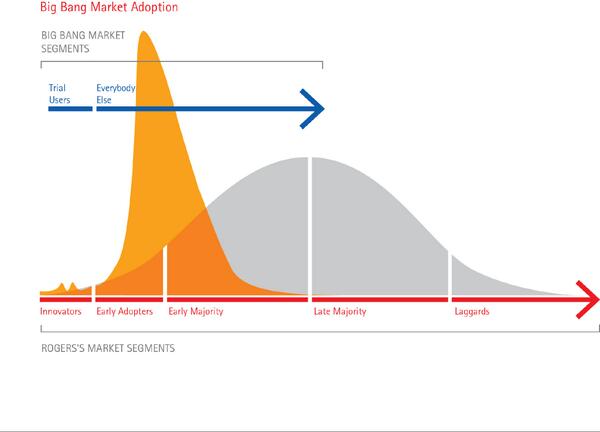

Making projections like these is really hard. Brilliant pundit Larry Downes titles his new book (co-authored with Paul Nunes) Big Bang Disruption: Strategy In an Age of Devastating Innovation. Its thesis is that with the advent of digital technology, entire product lines — indeed whole markets — can be rapidly obliterated as customers defect en masse and flock to a product that is better, cheaper, quicker, smaller, more personalized and convenient all at once.

Since adoption is increasingly all-at-once or never, saturation is reached much sooner in the life of a successful new product. So even those who launch these “Big Bang Disruptors” — new products and services that enter the market better and cheaper than established products seemingly overnight — need to prepare to scale down just as quickly as they scaled up, ready with their next disruptor (or to exit the market and take their assets to another industry).

Disruptors can come out of nowhere and happen so quickly and on such a large scale that it is hard to predict or defend against. “Sustainable advantage” is a concept alien to today’s technology markets. The reputation of the enterprise, aggregated customer bases, low-cost supply chains, access to capital and the like — all things that once gave an edge to incumbents — largely no longer exist or are equally available to far smaller upstarts. That’s extremely unsettling for business leaders because their function is no longer managing the present but inventing the future…all the time.

I certainly have no crystal ball. Yet just as makers of stand-alone vehicle GPS navigation devices were overwhelmed in 2013, suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere, by smartphone maps-app software, e.g., Google Maps, etc., so too do these iconic industries and services face a very real and immediate threat of big bang disruption this year.

Continue reading 5 Industries Facing Disruption In 2014

I’ve spent a fair amount of time at Project DisCo discussing how political, legal and regulatory processes in the United States are largely biased against disruptive innovators in favor of legacy incumbents. That’s typically just as true for Uber and its ride-hailing competitors as it is for Aereo, Hulu, Netflix and other streaming video — or over the top (“OTT”) — Internet television services. But perhaps no longer.

The Consumer Choice in Online Video Act (S.1680), introduced by Sen. Jay Rockefeller, chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee, aims to change things. The legislation’s stated objectives are to “give online video companies baseline protections so they can more effectively compete in order to bring lower prices and more choice to consumers eager for new video options” and to “prevent the anticompetitive practices that hamper the growth of online video distributors.” It does so by (a) requiring television content owners to negotiate Internet carriage arrangements with OTT providers in good faith, (b) guaranteeing such firms reasonable access to video programming by limiting the use of contractual provisions that harm the growth of online video competition, and (c) empowering the FCC to craft regulations governing the program access interface between online providers and traditional television networks and studios.

S.1680 is a remarkable legislative effort to predict where the nascent online programming market is headed. It anticipates that in order to fulfill their competitive potential, OTT video entrants will require similar legal protections to what satellite television providers have for years enjoyed. The bill applies the program access model developed several decades ago for satellite television to the new world of OTT video.

As Rockefeller explained:

[He] has watched as the Internet has revolutionized many aspects of American life, from the economy, to health care, to education. It has proven to be a disruptive and transformative technology, and it has forever changed the way Americans live their lives. Consumers now use the Internet, for example, to purchase airline tickets, to reserve rental cars and hotel rooms, to do their holiday shopping. The Internet gives consumers the ability to identify prices and choices and offers an endless supply of competitive offerings that strive to meet individual consumer’s needs.

But that type of choice — with full transparency and real competition — has not been fully realized in today’s video marketplace. Rockefeller’s bill addresses this problem by promoting that transparency and choice. It addresses the core policy question of how to nurture new technologies and services, and make sure incumbents cannot simply perpetuate the status quo of ever-increasing bills and limited choice through exercise of their market power.

Modeled explicitly on the controversial 1992 Cable Act (which itself passed only over a presidential veto), S.1680 appears to be the first piece of legislation embracing disruption as a procompetiitive form of market evolution, including as its initial congressional “finding” that OTT services have the potential to “disrupt the traditional multichannel video distribution marketplace.” That’s excellent. At the same time, the bill’s choice of solution is contentious, by subjecting vertically integrated cable and television providers (e.g., Comcast-NBCu) to another regime of program access and retransmission mandates. The legal standard fashioned for testing the validity of a television distribution contract in S.1680 is whether it “substantially deters the development of an online video distribution alternative.” Given the highly visible retransmission disputes that have arisen in recent months, such as the Tennis Channel and CBS, plus the lack of evidence that vertical integration in fact provides an incentive for exclusive dealing and content foreclosure, free market advocates are likely to object to this. Proponents of net neutrality rules, especially where data caps are concerned, have already spoken out in support.

Continue reading OTT Disruption: Is the “Rockefeller Bill” the Answer?

As a recent story from the The Washington Post illustrates well, “tradition” is a gating factor in the ongoing transformation of the legal industry. Despite the highly conservative nature of courts, bar associations and attorneys, however, in the post-Great Recession legal market of 2013, technology and changing values are rapidly disrupting traditional legal services.

My colleague and friend Jonathan Askin, Founder of the Brooklyn Law Incubator & Policy Clinic, hosted a seminar on legal start-ups in late August. Many of the companies highlighted there are focused on low-hanging fruit, taking the trend started by LegalZoom of moving do-it-yourself work product to consumers into spaces that for decades have remained buttoned-up by prohibitions against “unauthorized practice of law” and the resistance of lawyers to allowing clients document control. (LegalZoom itself has been challenged by bar groups and class action plaintiffs in North Carolina, Connecticut, Missouri and California for allegedly engaging in the practice of law, a classic and anticompetitive use of regulations designed to protect consumers, not prohibit new business models.) Like taxi-hailing companies Uber and Sidecar, legal start-ups thus face opposition from incumbents who are well-situated to employ archaic regulatory regimes to thwart new entry.

Nonetheless, the four emerging firms Askin profiled make a persuasive case that the guild-like barriers which for centuries protected lawyers from competition are breaking down before our eyes.

- Shake allows consumers to create binding contracts automatically on their smartphones or tablets with a few Q&As and then sign them electronically.

- Lawdingo leverages the power of networking to connect consumers to lawyers for real-time quick (and often free) answers on a virtually unlimited number of topics.

- Caserails offers cloud-based document assembly and editing functionalities for individuals or groups, long the bane of corporate transactions.

- Priori Legal allows SMBs to select among a trusted community of lawyers for discounted or fixed-rate engagements with Web-based comparison shopping.

The best and brightest of these firms will undoubtedly rise to the top over time. Much like banks in the 1970s — when toasters as deposit “gifts” were replaced by deregulated interest rates and tellers by ATMs — legal consumers no longer care or very much appreciate the old traditions of the legal profession, especially its convoluted language, fancy office space and expensive artwork. The successful start-ups in this steady disintermediation of legal services will be the ones who recognize that they are driven by what legal transactions can and will be, not what they have been historically, and that they are technology companies solving legal problems, not legal companies trying to understand technology. Continue reading Disrupting the Legal Industry

With the controversy surrounding the International Telecommunications Union (a UN treaty organization) just recently subsiding, it is time to take a look at Internet governance from a different perspective. We all know that laws and legal principles differ among countries. What many do not realize is that these laws — most completely non-tech oriented — are having a massive and negative impact on Internet innovation.

In America we proudly have the First Amendment, the fair use doctrine and the DMCA. The first limits the reach of liability for libel (defamation) at least to cases, for non-celebrities, where a publisher is at fault (i.e., negligent). Section 230 of the last allows ISPs, websites and Internet hosts a legal safe harbor from copyright and other legal offenses resulting from user-generated content or any other content that a customer, client or some third-party has published. These landmark legal regimes are hallowed in the U.S., for instance used to strike down overreaching Web censorship efforts by federal government. Fair use, in turn, permits non-commercial or transformative use of a portion of copyrighted content. Think Google image search thumbnails or blockquotes from a news source in someone’s blog or a movie clip in a televised review.

Things are very different elsewhere. Three cases in point.

- In Germany and perhaps soon other EU nations, search engines that display snippets of indexed Web pages in response to user queries are now by statute responsible for paying copyright royalties to the original publisher, regardless of whether the content owner charges for its stories with a paywall.

- In France, Italy, Ireland, Australia and now Japan, courts permit individuals to recover for libel based on autocomplete and search results that return incorrect or harmful personal information, but against the search provider, not the writer or content publisher.

- A Denmark court ruled deep linking illegal, as did Germany, leading some to believe that linking to a website other than the front page was illegal throughout Europe. While the German courts overturned that decision, it was Agence France Presse (AFP) which eventually sued Google News for brazenly daring to send search traffic to the organization’s news articles.

These results are foreign, literally, to U.S. jurisprudence. But they also illustrate a vitally important point. Legal regimes that have nothing to do with the Web are being applied in ways which upset existing services users take for granted and that threaten to impede future innovation. Linking is inherent in HTML and represents the essence of the Web. No one in America would argue seriously today that a hypertext URL link represents copyright violation. Search “autocomplete,” in turn, is not a creative activity, but a very useful technical advancement; it applies computer algorithms based on past searches to predict what the current user wants to see, speeding the retrieval of information from the Web. These results are foreign, literally, to U.S. jurisprudence. But they also illustrate a vitally important point. Legal regimes that have nothing to do with the Web are being applied in ways which upset existing services users take for granted and that threaten to impede future innovation. Linking is inherent in HTML and represents the essence of the Web. No one in America would argue seriously today that a hypertext URL link represents copyright violation. Search “autocomplete,” in turn, is not a creative activity, but a very useful technical advancement; it applies computer algorithms based on past searches to predict what the current user wants to see, speeding the retrieval of information from the Web.

Permitting autocomplete defamation suits against Google or Bing because other Web users have searched for information that damages an individual’s reputation is alien to our American way of thinking. It’s censoring completely accurate factual information about stuff on the Web, although that stuff may itself be factually wrong. The augmentation of liability is also just plain silly, because both autocomplete queries and search results themselves merely return an indexed link to something someone else has posted on the Web.

Continue reading Defamation, Autocomplete And Search Royalties: How Not To Govern the Internet

[This series of posts dissects the threatened FTC antitrust case against Google and concludes that a monopolization prosecution by the federal government would be a very bad idea. We divide the topic into five parts, one policy and four legal. Check out Part I and Part II.]

Antitrust law is characterized by rigorous, fact-intensive analysis, so much so that the prevailing jurisprudence holds that market definition (explored in Part II) generally should not be resolved on the “pleadings” alone, in other words without factual discovery. Nothing typifies the demanding analytical framework of antitrust more than monopoly power, part of the first element of a Section 2 monopolization case — possession of monopoly power in the relevant market. With respect to monopoly power, the potential case of FTC v. Google, Inc. will likely run into some especially significant barriers, no pun intended.

3. Google Has No Monopoly Power, Even In Internet Search/Advertising

There’s precious little room in a relatively brief blog series to expound on all the various elements that factor into a judicial finding of monopoly power. The basic principle is that a high market share (typically 70% or more), coupled with barriers to entry, allows an inference of monopoly power to be drawn. But like nearly all legal inferences that’s merely a rebuttable, prima facie construct, as direct proof of the “power to control price or exclude competition” is the best evidence of monopoly. (It’s just hard to find.)

This author has written elsewhere about The Fantasy Google Monopoly, in which I noted that “the reality is that Google neither acts like nor is sheltered from competition like the monopolists of the past, something the company’s critics never claim because they just can’t.”

Like the Red Queen in Through the Looking Glass, Google succeeds only by running faster than its competitors — merely to stay in the same place. There’s nothing about Internet search that locks users into Google’s search engine or its many other products. Nor is new entry at all difficult. There are few, if any, scale economies in search and the acquisition of data in today’s digital environment is relatively cost free. Microsoft’s impressive growth of Bing in a mere two or so years shows that new competition in search can come at any time.

While that sums up, rather cogently I must say, the antitrust analysis, let’s go to the coaches’ tape and break it down.

No Bottleneck or “Gateway” Control. Ten years ago, when the FCC and FTC both believed America Online — which boasted a very high share of dial-up Internet access — had monopoly power, the (fleeting) conclusion rested on the fact that AOL controlled access by its customers to the Internet and thus competing Internet content. Much like the pre-divestiture AT&T Bell System, the concern was that AOL held a “bottleneck” through which consumers had to pass to reach rivals. Yet Google does not own the Internet’s tramsission lines or 4G spectrum, and is thus not a bottleneck. Regardless of search share or volume, the reality is that Google has no  control over the content its search users can access on the Internet. Web search is one of many ways, together with links, URLs, browser bookmarks, directories, QR codes, email marketing and uncountable others, for Internet sites to drive traffic and hits. Google is not a gateway so much as it is a highly and quickly searchable index of the Web. When there’s a host of other ways to find a page, the index itself is just a convenience, as much for bound books as for Web sites. control over the content its search users can access on the Internet. Web search is one of many ways, together with links, URLs, browser bookmarks, directories, QR codes, email marketing and uncountable others, for Internet sites to drive traffic and hits. Google is not a gateway so much as it is a highly and quickly searchable index of the Web. When there’s a host of other ways to find a page, the index itself is just a convenience, as much for bound books as for Web sites.

No Power Over Price. Whether search ad rates are the price of search or alternatively the relevant antitrust market itself, they fail on the central monopoly power criterion of control over price. As micro-economics teaches, a monopolist can increase prices above marginal costs, resulting in a “deadweight” loss to consumer welfare. Yet Google’s search ads are priced via an auction system — the highest bidder for an advertising keyword buys the ads (as many or as few as it wants) at the winning bid price. Certainly, there are ways to game any auction to favor some bidders over others or to exert indirect influence on the wining auction price. But so far as we can tell, such a theory of pricing power is not involved in the FTC’s threatened monopolization claim against Google. And if it were, that case would be even harder to prove than this overview analysis concludes.

No Network Effects. Nothing symbolizes modern antitrust so much as an emphasis on so-called “network effects.” Network effects exist when the value of a product increases in proportion to the number of other users of the product, hence a name which originated in telephone antitrust cases, where subscriber demand for service rose in proportion to the number of interconnected telephone companies (and thus other telephone subscribers) the end user could call. Network effects are in part a barrier to entry, by increasing requirements for scale economies by new firms, and a source of power to exclude rivals, by allowing the dominant network effects firm to deny competitors critical mass. Yet there is no, or at least precious little, evidence that with respect to search users and search advertisers, there are any network effects at all involved with Google. That you may conduct Web searches using Google’s engine makes it no more likely that me or any other Web users will select Google for search. That Sears may buy some AdWords keywords for search advertising makes it only slightly if at all more likely (and a consequence of retail competition, not Google) that Macy’s will purchase search ads via a Google auction.

No Entry Barriers. A monopoly in a market in which entry by new competitors is unlimited cannot be sustained for long. Thus, as noted antitrust law couples market share with barriers to entry in assessing monopoly power. It is difficult if not impossible to make a serious case that there are substantial entry barriers in Internet search or advertising. Web page indexing — the key input to search — is a product of raw computing horsepower and storage capacity. Both are commodities with steadily falling prices, per Moore’s law, in today’s Internet economy. That Facebook is planing to launch its own search product says it all: entry into search only requires investment capital, which the antitrust laws rightfully do not regard as an entry barrier. As the UK’s Daily Mail wrote, “Facebook is looking to tackle Google by making search a much more prominent part of it social network.” The Red Queen strikes again.

“Data” Is Not a Search Entry Barrier. Proponents of a Google monopolization prosecution have recently refined their analysis, suggesting that the wealth of demographic data assembled by Google from users’ Web searches is a barrier to entry. That’s a smokescreen. Data about consumer preferences and behavior — aggregated and (much to the annoyance of privacy advocates) individualized — is also a commodity in our modern economy. Whether credit and commercial transaction data via the “big three” credit reporting agencies, product preference and consumer satisfaction data from J.C. Power and the like, or the emerging “big data” marketplace, data can easily be bought, in bulk, for cheap. (The U.S. legal presumption that a company owns, and thus can sell, data about its customers plays into this point, but is not relevant for antitrust purposes.) The corollary to this argument is that economies of scale pose a barrier to entry, an even more subtle concept which, unlike network effects, has not been recognized by mainstream antitrust courts as a dispositive Section 2 factor — every large-scale business enjoys scale economies, after all. Suffice it to say, the FTC would have to make new antitrust law if it relies on this novel theory, which seems to contradict the factual realities of the ubiquitous availability of inexpensive data and data storage on consumer preference and behavior today.

To sum up, claims that Google enjoys monopoly power in Internet search or search advertising fail in the face of the recognized criteria for that crucial Section 2 monopolization factor. Without monopoly power, unilateral (as opposed to concerted among competitors) action by a single firm is of no antitrust significance. Indeed, an implicit — and sometimes articulated — presumption in the arguments in favor of an FTC monopolization case is that Internet search is a “natural monopoly,” one dictated and preordained by the economic structure of the market. As an antitrust lawyer who while with the DOJ in the 1980s railed against the proposition that cable TV represented a natural monopoly — something satellite television and IPTV have at long last conclusively disproven — this author abhors that construct.

Even if they are correct, the parties pressing for government antitrust action against Google cannot claim the courts have ever recognized the concept of natural monopoly as a surrogate for the United States v. Grinnell Corp. requisite demonstration of actual monopoly power, willfully obtained or sheltered by exclusionary practices. We’ll turn to that question, whether Google has engaged in conduct antitrust law deems anticompetitive, next.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

[This series of posts dissects the threatened FTC antitrust case against Google and concludes that a monopolization prosecution by the federal government would be a very bad idea. We divide the topic into five parts, one policy and four legal. Check out Part I.]

Section 2 of the 1890 Sherman Act (15 U.S.C. § 2) makes “monopolization” unlawful. As every antitrust practitioner can recite by heart, this means that being a monopoly is not illegal, rather it is illegal to obtain or maintain monopoly power in a “relevant market” by exclusionary or anticompetitive means.

The most famous articulation of this basic principle comes from the case of United States v. Grinnell Corp. (“Grinnell“), 384 U.S. 563 (1966), in which the U.S. Supreme Court explained that a monopoly position reached as a result of a “superior product, business acumen or historic accident” is different from one achieved by the “willful acquisition or maintenance of that power.” That slightly schizophrenic approach reflects the basic conflict within antitrust itself. The law encourages, and permits, firms with market power (typically a synonym for monopoly power, although economists disagree at the margins) to compete aggressively on the merits, and even to eliminate competitors. Yet to tame the results of unbridled capitalism, Section 2 constrains companies from creating or defending monopoly power with anticompetitive practices.

2. Internet Search and Search Advertising are Not Relevant Antitrust Markets

The starting point for every antitrust case is market definition — outlining the contours of a market, in which the defendant participates, in order to assess whether the firm possesses monopoly power in that market. In defining the relevant antitrust market, courts determine which products compete with the defendant’s product and thus limit or prevent the exercise of market power. Typically, this process involves examining substitutability of products (both from a demand and a supply perspective) to find whether consumers and rivals could switch to another source (or sources) if the defendant firm were to raise price or restrict output. For example, in the 1950s chemical innovator duPont was charged with monopolizing the cellophane market, a product it invented, but the courts ruled that the relevant antitrust market could not be so narrowly limited because cellophane was interchangeable with other food wrapping materials. The “great sensitivity of customers in the flexible packaging markets to price or quality changes” prevented duPont from exerting monopoly control over price.

The more broadly the relevant antitrust market is defined, the less likely it is the defendant has the ability to exercise monopoly power in that market. As a corollary, if the targeted firm does not have monopoly power in the relevant market, there generally cannot be Section 2 liability. Many recent antitrust cases, including the FTC’s controversial attempt to block Whole Foods’ acquisition of Wild Oats and the Justice Department’s challenge to the Oracle-PeopleSoft merger, have turned on market definition.

With that background, let’s look at the purported “Internet search” market. That’s obviously the core proposition in any attack on Google for unlawful monopolization, because the necessary premise is that Google’s dominant share — estimated at from 65 to 80% — of Web searches is the foundation of its alleged monopoly. But here the antitrust analysis begins to break down. Internet search is a free product in which the consumers (Internet users) are charged nothing, with the service supported by advertising revenues. Since monopoly power is the “power to control price or exclude competition,” one must necessarily ask whether Google’s high “market share” reflects any market power at all. More importantly, search users are just like broadcast television viewers; they are an input into a different product — search advertising — in which consumers themselves are effectively sold by virtue of advertising rates based largely on impressions and click-throughs. Just as NBC, ABC, CBS and Fox compete for television eyeballs in order to sell more advertising (hence profiting) to sponsors, so too do Internet search engines monetize the service by selling eyeballs to advertisers.

Google’s share of search by itself is therefore almost meaningless. Even if the relevant market is confined to search, moreover, there is nothing that enables Google to prevent users from switching, instantaneously, to another of the scores of search engine providers on the Internet. (It should go without saying that even the government does not contend that Google displaced Yahoo!, Alta Vista, Ask.com and the many former search giants that dominated the Internet in the 1990s with anything other than better, more useful, search results, a consequence of better algorithms — the epitome of Grinnell’s “superior product.”) So the relevant market analysis must therefore focus on the area where Google in fact competes with other search engine providers, namely in the sale of search advertising. We all know that the links displayed alongside so-called “organic” search results are paid, listed conspicuously as “sponsored” results. Without search advertising, in today’s Internet economy there would be no free search engine services.

Continue reading Why An FTC Case Against Google Is A Really Bad Idea (Part II)

Folks in the tech industry have for the most part been conspicuously silent, at least publicly, about the Federal Trade Commission’s lengthy investigation of and apparent intention — perhaps as soon as year end — to file an antitrust case against Google for monopolization. In part that’s because Silicon Valley companies typically do not understand or want to get bogged down in legal and political controversies. In part, it’s because many tech innovators realize that staying part of Google’s AdWords ecosystem can be very profitable.

This silence is not driven by fear of retaliation, as Google has never done that to its vertical channel partners or even erstwhile ex-corporate joint venturers like Apple and Yahoo!. But it is likely emboldening the FTC to think that the Washington, DC agency has the interests of competition in high-tech at heart in moving against Mountain View. That’s a disquieting conclusion which should be especially troubling to young Internet-centric companies from Facebook and Twitter to shoestring-funded app developers. This silence is not driven by fear of retaliation, as Google has never done that to its vertical channel partners or even erstwhile ex-corporate joint venturers like Apple and Yahoo!. But it is likely emboldening the FTC to think that the Washington, DC agency has the interests of competition in high-tech at heart in moving against Mountain View. That’s a disquieting conclusion which should be especially troubling to young Internet-centric companies from Facebook and Twitter to shoestring-funded app developers.

This series of posts dissects the threatened FTC case and concludes that a monopolization prosecution by the federal government of Google would be a very bad idea. We divide the topic into five parts, one policy and four legal. We’ll start with policy because that’s something which does not turn on the rather arcane elements of antitrust law.

Continue reading Why An FTC Case Against Google Is A Really Bad Idea (Part I)

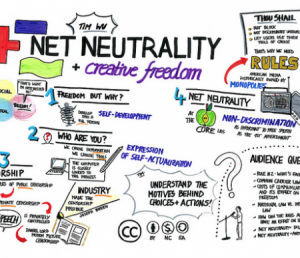

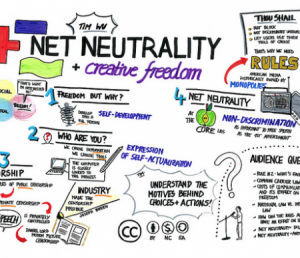

The news today is all about Tuesday’s “open meeting” at the FCC, where at long last a proposed regime for network neutrality will formally be considered. “There are of course a lot of moving pieces surrounding this debate, and however the chips fall, it’s going to have a long-term affect over how the Internet operates over the next several years.” The FCC Votes on Net Neutrality Tomorrow; The Internet Waits | AllThingsD.

Actually, the modest few rules FCC Chairman Genachowski has proposed are so trivial that, like all good policy, compromises or settlements, they have angered both the left and the right. The former deplores the scheme as worse than nothing, while the latter says it is a slippery slope to full regulation of the Internet.

The far more important issue tomorrow is the legal framework under which the FCC will propose net neutrality rules. After the Comcast decision in April of this year — in which a federal court of appeals threw out the Commission’s decision to sanction undisclosed throttling of P2P traffic by ISPs — net neutrality has been in a state of extreme jurisdictional chaos. For an overview, read the Fall 2010 edition of the ABA’s Icarus magazine, a symposium issue on so-called “Title II reclassification” featuring, among others, this author.

About a month ago, Genachowski also announced has was abandoning his Third Way reclassification approach. That’s a brilliant decision, as reclassification was doomed to judicial reversal and, almost certainly, an injunction or stay against implementation. The alternative is for the FCC to articulate the ancillary jurisdiction linkage or nexus between the agency’s specific areas of delegated responsibility — telephony (Title II) and broadcasting (Title III) — and its general authority over “communications by wire or radio.” Yet to do that the agency needs to distance itself from the protectionist roots and core of the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, which for 40+ years has been used principally to squelch or constrain new technologies in order to prevent market competition with older, established industries (constituencies).

Here’s what I wrote earlier:

Ancillary jurisdiction under Southwestern Cable represents the low-water mark of communications jurisprudence. It was fashioned as a legal matter to permit FCC control of CATV, the infant predecessor to today’s robust cable programming industry, as a means of protecting the Commission’s power to regulate broadcast television. . . . It was protectionism to the core [and] epitomizes the conservative critique of administrative agencies as regulatory capture.

There is no longer an appetite in Congress to utilize governmental regulation to protect incumbents and vested commercial interests against competition and new entry. Hence, because it lacked and still lacks the political will to justify net neutrality on the ground of protecting its Title II and III jurisdiction over telephony and broadcasting — by sheltering the legacy providers of those services against disintermediation — the agency can never provide the requisite “nexus” demanded by the Comcast opinion.

Since no current policy or political figure today can admit to using regulation to handicap new entrants and favor established business interests, ancillary jurisdiction will remain the dark, dirty secret of administrative law until it is moved to a new footing. Imagine if the FCC reasoned that with IP convergence, services that formerly were within its Communications Act authority, like telephony and television, are increasingly moving to an Internet-based delivery system that, if it continues, will eventually leave all of communications beyond the FCC’s jurisdiction. Under this approach, the Commission could demonstrate a clear nexus between its statutorily delegated responsibilities and the ancillary role it proposes for net neutrality, without reverting to the sullied, protectionist past of ancillary jurisdiction.

Some observers may argue that such a “Title I” approach to net neutrality does not in principle prevent the FCC from exercising unlimited power over Internet communications. That’s overstated in my view. First, the Supreme Court’s 1970s decisions on ancillary jurisdiction (Midwest Video) hold that ancillary jurisdiction us not “unbounded.” Second, from a legislative perspective it is obvious that an administrative agency acting on the basis essentially of implied power cannot do anything broader under a general “public interest” standard than it could if acting under the express jurisdiction delegated by Congress. Specifically, while Title II authorizes full, rate-of-return common carrier regulation, the FCC would overstep its bounds imposing parallel rules under Title I ancillary jurisdiction. Third, the extreme critique from conservatives that agencies cannot be permitted to do anything without express congressional authorization really doesn’t apply; Congress has granted Title I authority over all interstate communications, it just has not fleshed that out with detailed standards.

More problematic are current reports that the FCC is considering relying on Section 706 of the Act, which urges the agency to promote “advanced telecommunications” services, as its ancillary jurisdiction hook for net neutrality. That’s inane, because the Commission in the 1990s ruled over and over again that 706 was not a basis for regulatory power. This means that using 706 as the nexus for ancillary jurisdiction will necessarily stoke a hotter fight over the FCC’s reversal of its statutory interpretation, a double whammy.

The better linkage is to the basic legislative commands (e.g., Section 201) that direct the FCC to ensure just and reasonable communications and broadcasting services for users. It cannot be disputed that if current trends continue, VoIP and Internet video could and well may eventually displace POTS and cable/broadcasting, in which case there would be nothing left with which the FCC could fulfill these elementary responsibilities if such IP-based services, which do not represent “telecommunications,” “cablecasting” or “broadcasting” in traditional statutory terms, must remain forever and completely unregulated.

A broader and more cogent question is, if the FCC takes this approach, would that not create a system in which an agency decides for itself how far to go when Congress fails to update its underlying statutory power to reflect technological change? Yes, it would. But it would not be Genachowski or the FCC creating this paradigm, it was the Supreme Court. A better legal system would have an administrative agency go back to Congress and ask for new powers if its old ones are being end-run by technology. As a practical matter, that could lead to gridlock, however, as in the communications arena general revisions of the Communications Act of 1934 happen very rarely — once in 65 years, far less than every generation.

So if politics is the art of the possible, it is possible for the FCC this Tuesday to make history, survive a judicial challenge and move archaic regulatory jurisprudence forward into a new era, stripped of its protectionist past. It’s also possible the Commission will be split politically, that left-wing proponents can convince some members that a principled loss is better than a compromise win, see Net Neutrality Supporters Question FCC’s Genachowski Plan | Techworld.com, or that as it has so many times in the past, the agency will fail to explain itself in simple terms the courts demand and can understand.

The Third Way of Title II reclassification was too cute for its own good. The Commission has a chance to correct that overreaching, but its internal bureaucratic tendencies to ambiguity and a “Chinese menu” theme for jurisdiction threaten to blow up net neutrality again. GOP Opposition to FCC Net Neutrality Plan Mounts | enterprisenetworkingplanet.com. Far more principled, regardless of one’s position on the substantive merits and policy need for network neutrality, would be for the FCC to pick a single, simple nexus. It’s not cute, it’s not expansive, but it would work. The question is whether in this highly polarized legal and political environment, the players really want anything to work at all.

Politics is always, in part, theater and sausage-making. That the law and public policy are the byproducts of such superficial pursuits remains a frustration, but in the United States it’s one we all have to live with, and one some pundits are convinced preserves the republican tradition of limited government. I for one hope the FCC keeps a more modest agenda tomorrow and moves the net neutrality debate closer to a conclusion, instead of adding fuel to the legal and policy fires that have raged on this issue for years.

|

|

but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider.

but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider.