A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

With the controversy surrounding the International Telecommunications Union (a UN treaty organization) just recently subsiding, it is time to take a look at Internet governance from a different perspective. We all know that laws and legal principles differ among countries. What many do not realize is that these laws — most completely non-tech oriented — are having a massive and negative impact on Internet innovation.

In America we proudly have the First Amendment, the fair use doctrine and the DMCA. The first limits the reach of liability for libel (defamation) at least to cases, for non-celebrities, where a publisher is at fault (i.e., negligent). Section 230 of the last allows ISPs, websites and Internet hosts a legal safe harbor from copyright and other legal offenses resulting from user-generated content or any other content that a customer, client or some third-party has published. These landmark legal regimes are hallowed in the U.S., for instance used to strike down overreaching Web censorship efforts by federal government. Fair use, in turn, permits non-commercial or transformative use of a portion of copyrighted content. Think Google image search thumbnails or blockquotes from a news source in someone’s blog or a movie clip in a televised review.

Things are very different elsewhere. Three cases in point.

- In Germany and perhaps soon other EU nations, search engines that display snippets of indexed Web pages in response to user queries are now by statute responsible for paying copyright royalties to the original publisher, regardless of whether the content owner charges for its stories with a paywall.

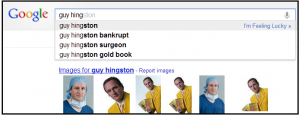

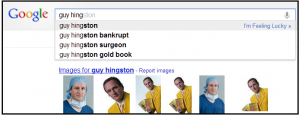

- In France, Italy, Ireland, Australia and now Japan, courts permit individuals to recover for libel based on autocomplete and search results that return incorrect or harmful personal information, but against the search provider, not the writer or content publisher.

- A Denmark court ruled deep linking illegal, as did Germany, leading some to believe that linking to a website other than the front page was illegal throughout Europe. While the German courts overturned that decision, it was Agence France Presse (AFP) which eventually sued Google News for brazenly daring to send search traffic to the organization’s news articles.

These results are foreign, literally, to U.S. jurisprudence. But they also illustrate a vitally important point. Legal regimes that have nothing to do with the Web are being applied in ways which upset existing services users take for granted and that threaten to impede future innovation. Linking is inherent in HTML and represents the essence of the Web. No one in America would argue seriously today that a hypertext URL link represents copyright violation. Search “autocomplete,” in turn, is not a creative activity, but a very useful technical advancement; it applies computer algorithms based on past searches to predict what the current user wants to see, speeding the retrieval of information from the Web. These results are foreign, literally, to U.S. jurisprudence. But they also illustrate a vitally important point. Legal regimes that have nothing to do with the Web are being applied in ways which upset existing services users take for granted and that threaten to impede future innovation. Linking is inherent in HTML and represents the essence of the Web. No one in America would argue seriously today that a hypertext URL link represents copyright violation. Search “autocomplete,” in turn, is not a creative activity, but a very useful technical advancement; it applies computer algorithms based on past searches to predict what the current user wants to see, speeding the retrieval of information from the Web.

Permitting autocomplete defamation suits against Google or Bing because other Web users have searched for information that damages an individual’s reputation is alien to our American way of thinking. It’s censoring completely accurate factual information about stuff on the Web, although that stuff may itself be factually wrong. The augmentation of liability is also just plain silly, because both autocomplete queries and search results themselves merely return an indexed link to something someone else has posted on the Web.

Continue reading Defamation, Autocomplete And Search Royalties: How Not To Govern the Internet

This is the brief I just prepared for the Consumer Federation of America to the U.S. Supreme Court on the issue of whether the so-called Red Lion doctrine of First Amendment regulation of broadcasters should be re-examined. My favorite passage is:

[T]he presumption of invalidity inherent in petitioners’ argument is flawed. Broadcasters do not remain “singularly constrained,” Pet. at 16, on the ground that there were few speakers 45 years ago. When Red Lion was decided there were hundreds more newspapers in America, half a dozen or more in major cities like New York, national, weekly news and cultural magazines (Life, Look, etc.) and many other sources of information and entertainment that are no longer available in today’s marketplace. Therefore, the “undeniably large increase in the number of broadcast stations and other media outlets” on which the D.C. Circuit and petitioners rely, id. at 18, is immaterial to the economic regulation of broadcast licensees unless — as petitioners dare not suggest, because it is untrue — the increase has lessened the technical need for governmental entry and interference regulation.

Whether there are three or six or ten television stations in a local market, however, does not at all mean there is enough spectrum to accommodate everyone who would like to use the airwaves. What some judges have called “the indefensible notion of spectrum scarcity,” Action For Children?’s Television v. FCC, 105 F.3d 723, 724 n.2 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (Edwards, J., dissenting), is therefore totally true and completely defensible.

[slideshare id=11925599&doc=11-696cfaopp-brief-120308132113-phpapp02&type=d]

It is rare that the justices of the Supreme Court of the United States actually write or speak about technology. But as connectivity and user-generated content become more ubiquitous and pervasive, sometimes the Court — despite its inherent judicial conservatism — just can’t avoid touching on issues related to the use, importance and legal status of modern communications technologies.

In that respect, the just-completed 2009-10 and 2010-11 Supreme Court terms witnessed two rather impressive developments. First, while more than a year ago most of the justices, and especially Antonin Scalia, said they had never even heard of Twitter, 2010 saw the first-ever mention of blogs and “social media” in a Supreme Court opinion, namely the controversial Citizens United decision on corporate campaign spending.

Rapid changes in technology — and the creative dynamic inherent in the concept of free expression — counsel against upholding a law that restricts political speech in certain media or by certain speakers. Today, 30-second television ads may be the most effective way to convey a political message. Soon, however, it may be that Internet sources, such as blogs and social networking Web sites, will provide citizens with significant information about political candidates and issues. Yet, §441b would seem to ban a blog post expressly advocating the election or defeat of a candidate if that blog were created with corporate funds. The First Amendment does not permit Congress to make these categorical distinctions based on the corporate identity of the speaker and the content of the political speech.

Citizens United v. FEC, 130 S. Ct. 876, slip op. at 49 (2010) (emphasis added; citations omitted).

Second, in this spring’s ruling overturning California’s regulation of violent video game sales to minor children — a/k/a teenage gamers — a sharply divided Court grappled not with the previously undecided question of whether video games merit First Amendment protection (on which there was unanimity), but instead the far narrower one of how to show a “compelling state interest” in restricting speech directed to children. That led to a remarkable passage, from Scalia himself, which as is typical was relegated to a footnote (where the “good stuff” is often found):

Justice Alito accuses us of pronouncing that playing violent video games “is not different in ‘kind’” from reading violent literature. Well of course it is different in kind, but not in a way that causes the provision and viewing of violent video games, unlike the provision and reading of books, not to be expressive activity and hence not to enjoy First Amendment protection. Reading Dante is unquestionably more cultured and intellectually edifying than playing Mortal Kombat. But these cultural and intellectual differences are not constitutional ones. Crudely violent video games, tawdry TV shows, and cheap novels and magazines are no less forms of speech than The Divine Comedy, and restrictions upon them must survive strict scrutiny—a question to which we devote our attention in Part III, infra. Even if we can see in them “nothing of any possible value to society . . ., they are as much entitled to the protection of free speech as the best of literature.” Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507, 510 (1948).

Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Assn., slip op. at 9 n.4 (2011) (emphasis added).

So the lesson is that although Justice Scalia may not know how to Tweet, but he can spell perfectly the name of a classic martial arts videogame, while still believing that The Divine Comedy is of greater value to society. What would the modern, technophile generation think about that? We’ll probably never know, because those facile with the means for mobile and rapid communications have short attention spans and thus probably lack have the patience (interest aside) to read Dante, even the Cliff Notes version, and tell us!

Yesterday a federal district judge ruled the “National Day of Prayer” unconstitutional. But observing such a commemorative occasion involved no compulsion, discrimination or penalty on or against any observer of any religious doctrine. So what’s the rub?

Lots of Americans realize the First Amendment protects freedom of religion. It actually has two parts. The 1st guarantees the “free exercise” of religious beliefs. The 2nd prohibits any “establishment of religion” by the government. It’s the second clause — known unoriginally as the “establishment clause” — that is in play when debating invocations at public events, schools and the like.

“A determination that the government may not endorse a religious message is not a determination that the message itself is harmful, unimportant, or undeserving of dissemination,” she said. “Rather it is part of the effort to carry out the Founders’ plan of preserving religious liberty to the fullest extent possible in a pluralistic society.”

Personally I think there’s a difference between making all elementary school students recite the Lord’s Prayer and ordaining a national day, really just an honorific, to recognize the role of prayer in American society. The former was declared unconstitutional in the early 1960s and few citizens today would object to that significant step toward religious tolerance and diversity. But as a constitutional matter, it is simply not the case that the US Constitution’s protections for religious freedom mean the government can support or promote either specific denominations (e.g., Anglicans over Baptists) or movements (e.g., Christianity over all the rest). At the margin, things like a National Prayer Day have little relevance except to those who stand on principle and refuse to compromise, which in US constitutional jurisprudence has always been a discrete and insular minority.

There has been a lot of talk, debate and criticism — leveled at Google, Microsoft and other major Internet content providers — about censorship of Internet content by the government of China. Google v. China: Principled, Brave, or Business As Usual? [Huffington Post]. The assumption most of these pundits make is that mandatory filtering and blocking of the Internet is a policy embraced only by repressive or authoritarian regimes. That’s not at all correct.

Iran's Green Revolution Western nations are just as bad; worse in some ways. “Enemies of the Internet”: Not Just For Dictators Anymore [ReadWriteWeb]. As a few for instances:

Reporters Without Borders recently released a penetrating study of government Internet censorship, titled “Enemies of the Internet 2010.” It cogently observes:

Western democracies are not immune from the Net regulation trend. In the name of the fight against child pornography or the theft of intellectual property, laws and decrees have been adopted, or are being deliberated, notably in Australia, France, Italy and Great Britain. On a global scale, the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), whose aim is to fight counterfeiting, is being negotiated behind closed doors, without consulting NGOs and civil society. It could possibly introduce potentially liberticidal measures such as the option to implement a filtering system without a court decision.

So Internet censorship is alive and well in the world’s “progressive” industrialized nations. The liberating technology of the Web is under assault because, as in 2009’s “green revolution” in Iran via Twitter, it can catalyze viral growth in political opposition and tends to harbor folks, like pedophiles, who’s activities are politically disfavored (even repulsive). No one lobbies for child pornographers, after all.

Just do not operate under the misimpression that it is only Saudi Arabia, Syria, North Korea, Vietnam, China and the like that censor Internet content. Almost all governments do it. The United States, with its constitutional First Amendment protection for free speech, and the Scandinavian countries — where the Pirate Party was victorious in Swedish parliamentary elections — which have classified Internet access as a fundamental human right, are the exceptions. This blogger, for one, hopes the exception swallows the rule. One can always hope.

|

|

These results are foreign, literally, to U.S. jurisprudence. But they also illustrate a vitally important point. Legal regimes that have nothing to do with the Web are being applied in ways which upset existing services users take for granted and that threaten to impede future innovation. Linking is inherent in HTML and represents the essence of the Web. No one in America would argue seriously today that a hypertext URL link represents copyright violation. Search “autocomplete,” in turn, is not a creative activity, but a very useful technical advancement; it applies computer algorithms based on past searches to predict what the current user wants to see, speeding the retrieval of information from the Web.

These results are foreign, literally, to U.S. jurisprudence. But they also illustrate a vitally important point. Legal regimes that have nothing to do with the Web are being applied in ways which upset existing services users take for granted and that threaten to impede future innovation. Linking is inherent in HTML and represents the essence of the Web. No one in America would argue seriously today that a hypertext URL link represents copyright violation. Search “autocomplete,” in turn, is not a creative activity, but a very useful technical advancement; it applies computer algorithms based on past searches to predict what the current user wants to see, speeding the retrieval of information from the Web.