A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

The strangely named Rockstar Consortium has been in the news again, in part because some of its members just formed a new lobbying group, the Partnership for American Innovation, aimed at preventing the current political furor over patent trolls from bleeding into a general overhaul of the U.S. patent system. Yet Rockstar is perhaps the most aggressive patent troll out there today. Hence the mounting pressure in Washington, DC for the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division — which signed off on the initial formation of Rockstar two years ago — to open up a formal probe into the consortium’s patent assertion activities directed against rival tech firms, principally Google, Samsung and other Android device manufacturers.

Usually the fatal defect in antitrust claims of horizontal collusion is proving that competing firms acted in parallel fashion from mutual agreement rather than independent business judgment. In the case of Rockstar — a joint venture among nearly all smartphone platform providers except Google — that problem is not present because the entity itself exists only by agreement among its owner firms. The question for U.S. antitrust enforcers is thus the traditional substantive inquiry, under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, whether Rockstar’s conduct is unreasonably restrictive of competition.

Despite its cocky moniker, Rockstar is simply a corporate patent troll hatched by Google’s rivals, who collectively spent $4.5 billion ($2.5 billion from Apple alone) in 2012 to buy a trove of wireless-related patents out of bankruptcy from Nortel, the long-defunct Canadian telecom company. It is engaged in a zero-sum game of gotcha against the Android ecosystem. As Brian Kahin explained presciently on DisCo then, Rockstar is not about making money, it’s about raising costs for rivals — making strategic use of the patent system’s problems for competitive advantage. Creating or collaborating with trolls is a new game known as privateering, which allows big producing companies to do indirectly what they cannot do directly for fear of exposure to expensive counterclaims. Essentially, it’s patent trolling gone corporate. As another pro-patent lobbying group said at the time, Rockstar represents “a perfect example of a ‘patent troll’ — they bought the patents they did not invent and do not practice; and they bought it for litigation.” Predictiv’s Jonathan Low put it quite well in his The Lowdown blog:

The Rockstar consortium, perhaps more appropriately titled “crawled out from under a rock,” is using classic patent troll tactics since their own technologies and marketing strategies have fallen short in the face of the Android emergence as a global power. Those tactics are to buy patents in hopes of finding cause, however flimsy, to charge others for alleged violations of patents bought for this purpose. Rockstar calls this “privateering” in order to distance itself from the stench of patent trolling, but there are no discernible differences.

Continue reading Rockstar’s Patent Trolling Conspiracy

With reality television all the rage, viewers may wonder why there’s been no reality series about the inbred high-tech ecosystem of Silicon Valley. There should be, because the reality of how our technology bastion really competes today — namely by patent litigation and acquisitions — is astonishing.

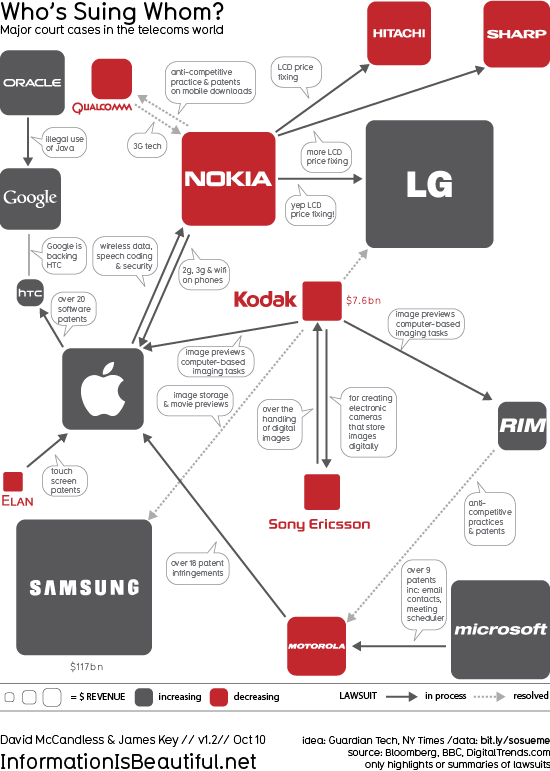

Last year Google, Apple, Intel and other leading Silicon Valley companies were targeted by federal antitrust enforcers for tacitly agreeing not to hire each other’s key employees. Such a conspiracy could have landed top executives in jail. This year Apple, Samsung, Google, Nokia and others have all been battling over back-and-forth claims that smartphones and wireless tablets infringe each others’ U.S. patents. Now, just weeks after Google’s general counsel objected that patents are gumming up innovation, the search behemoth has announced its own $12.6 billion acquisition of Motorola Mobility, and with it their own portfolio of wireless patents, just a fortnight after purchasing a relatively few (“only” 1,000 or so ) wireless patents from IBM.

While the executives at Google have nothing to fear personally from these patent wars, others seem to have a lot at risk. That is because, according to the Wall Street Journal, the U.S. Justice Department’s Antitrust Division is investigating another possible conspiracy among Silicon Valley companies. This one arises out of the collective bid in the late spring of nearly every wireless phone operating system manufacturer, except Google, for a portfolio of 6,000 cell phone patents formerly held by bankrupt Canadian company Nortel. Simply put, Google started the bidding at about $1 billion, but the others joined forces to lift the price to an astounding $4.5 billion and win the prize.

That’s the legal background to Google’s just-announced Motorola Mobility acquisition, and it’s one that could have serious anticompetitive consequences. If the curiously named “Rockstar Bidco” consortium — which includes Microsoft, Apple, RIM, EMC, Ericsson and Sony — refuses to license the erstwhile Nortel patents to Google for its Android wireless operating system, they will be agreeing as “horizontal” competitors not to deal with a rival. Classically such group boycotts are treated as a serious antitrust no-no, and a criminal offense. If the group licenses the patents, on the other hand, they could be guilty of price fixing (also a possible criminal offense), since a common royalty price was not essential to the joint bid and would eliminate competition among the members for licensing fees.

If the Rockstar Bidco companies decide to enforce the patents by bringing infringement litigation against Google, things could be even worse. Patent suits themselves, unless totally bogus, are usually protected from antitrust liability so as not to deter legitimate protection of intellectual property assets. (That does not mean they’re competitively good, since patent suits are often just a means of keeping rivals out of the marketplace.) Nonetheless, a multi-plaintiff lawsuit by common owners of patents would have those same horizontal competitors agreeing on lots of joint conduct, well beyond mere license rates. For starters, is the objective of such an initiative to kill Android by impeding its market share expansion? That’s a valid competitive strategy, standing alone, for any one company; it takes on a totally different dimension when firms collectively controlling a dominant share of the market gang up on one specific rival.

Google’s broader complaint that patent litigation in the United States is too expensive, too uncertain and too long may well be right. This bigger issue is being debated in Washington, DC as part of what insiders call “patent reform.” The high-stakes competitive battles being waged today in the wireless space under the guise of esoteric patent law issues like “anticipation” by “prior art” suggest a thoroughly Machiavellian approach to the legal process, just as war is merely diplomacy by other means. They inevitably color the perspective of policy makers, who watch with regret as a system designed to foster innovation gets progressively buried with expensive suits, devious procedural maneuvering and legalized judicial blackmail.

Even the biggest companies, though, would find it hard to compete if their largest rivals were allowed to form a members-only club around essential technologies to which only they had access. Microsoft’s own general counsel countered two weeks ago that Google was invited to join an earlier consortium bid but declined before the Nortel auction. Embarrassing, yes; dispositive, no. If the offer were still open, now that it is clear Google’s principal wireless rivals are all members, things would be different. Indeed, there’s even an opposite problem of antitrust over-inclusiveness where patents and patent pools are concerned. If everyone in an industry shares joint ownership of the same basic inventions, where’s the innovation competition? Google’s defensive purchase of Motorola is a desperate, catch-up move that does not really change this “everyone-but-Android” reality.

Silicon Valley’s patent wars are for good reason not nearly as popular as Bridezillas or So You Think You Can Dance. Yet they are far more important, economically, to Americans addicted today to their smartphones and spending hundreds of dollars monthly on wireless apps and services. Whether the Justice Department will challenge the Rockstar Bidco consortium or give it a free pass remains to be seen. From a legal perspective, it is just a shame the subject is too arcane, and certainly way too dull, to make a reality TV series.

The battle to beat Google’s Android mobile phone OS is quickly turning into a legal bonanza. Apple is suing HTC, Samsung and Motorola, all makers of wireless phones with the Android platform. Oracle is seeking up to $6.1 billion in a patent lawsuit against Google, alleging Android infringes Oracle’s Java patents. And Microsoft is suing Motorola over its Android line.

That’s all perfectly fine from an antitrust and competition standpoint — leaving aside the harder policy question of whether using patent infringement litigation to block competition should be permissible. Enforcing property rights is a legitimate and rational business activity that, absent “sham” lawsuits, is not second-guessed by antitrust enforcement agencies or courts. There can be exclusionary consequences, but they are a result of the patent laws in the first instance, not of themselves anything anticompetitive by the patent holder.

A much more troubling aspect of the increasing IP (or “IPR” as they say across the pond) battles surrounding Android is the recent sale of Nortel’s 6,000 or so wireless patents at a bankruptcy auction in Canada to a collection of bidders including Apple, Microsoft, RIM, EMC, Ericsson and Sony. How Apple Led The High-Stakes Patent Poker Win Against Google, Sealing Ballmer’s Promise | TechCrunch. The winning consortium bid more than $4.5 billion — some five times Google’s opening bid and, according to some pundits, far more than the portfolio was worth — to gain control of the patents.

“Why is the portfolio worth five times more to this group collectively than it is to Google?” said Robert Skitol, an antitrust lawyer at the Drinker Biddle firm. “Why are three horizontal competitors being allowed to collaborate and cooperate and join hands together in this, rather than competing against each other?”

Antitrust Officials Probing Sale of Patents to Google’s Rivals | Washington Post.

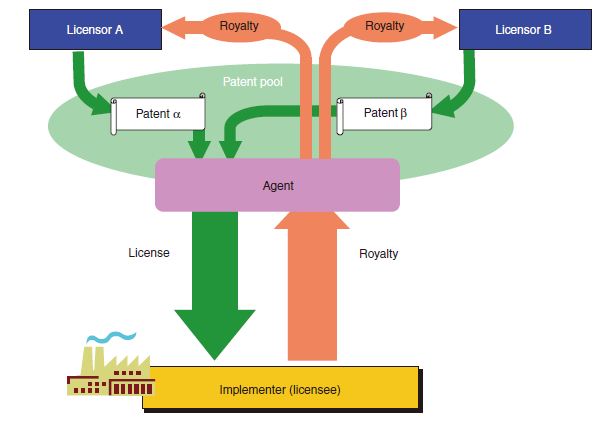

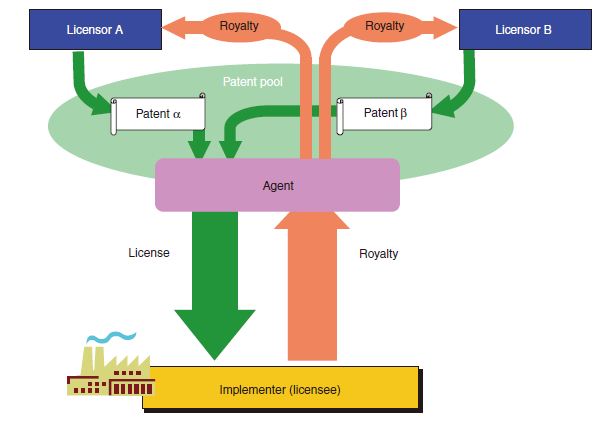

These are good questions. Patent “pools,” which are collections of horizontal competitors sharing patent licenses among themselves, are today generally considered procompetitive under the antitrust laws where they (a) are limited to technologically essential or “blocking” patents, and (b) do not contain ancillary restraints, such as resale price-setting or restrictions on participant use of alternative technologies. (MPEG, WiFi, LTE and other communications technologies are prime examples of patent pools.) The theory is that, with price effects eliminated, the cross-licensing of patents that might otherwise be used to block entry into a market reduces barriers to entry and increases efficiency.

Yet the consortium which won the Nortel wireless portfolio, revealing dubbed “Rockstar Bidco,” includes nearly everyone in the mobile phone and wireless OS businesses except Google. If these players agreed among themselves not to license their own patents to Google, that would be a per se illegal group boycott (also known as a concerted horizontal refusal to deal). Competitors cannot allocate markets or conspire to keep a rival out of the marketplace. It is unclear whether Google was invited to join Rockstar Bidco, but unless Larry, Sergey and Eric turned down such an offer, it seems a fair case can be made that the consortium bid was in effect an implicit horizontal agreement not to include Google. Post-auction, the reality of licenses will clearly tell us whether the joint ownership structure was a pretext to cover a refusal to deal. No one knows what the consortium intends to do with the Nortel patent portfolio; they won’t say. Microsoft, RIM And Partners Mum On Plans For Nortel Patents | Forbes. Yet the consortium which won the Nortel wireless portfolio, revealing dubbed “Rockstar Bidco,” includes nearly everyone in the mobile phone and wireless OS businesses except Google. If these players agreed among themselves not to license their own patents to Google, that would be a per se illegal group boycott (also known as a concerted horizontal refusal to deal). Competitors cannot allocate markets or conspire to keep a rival out of the marketplace. It is unclear whether Google was invited to join Rockstar Bidco, but unless Larry, Sergey and Eric turned down such an offer, it seems a fair case can be made that the consortium bid was in effect an implicit horizontal agreement not to include Google. Post-auction, the reality of licenses will clearly tell us whether the joint ownership structure was a pretext to cover a refusal to deal. No one knows what the consortium intends to do with the Nortel patent portfolio; they won’t say. Microsoft, RIM And Partners Mum On Plans For Nortel Patents | Forbes.

This author happens not to be a fan of Android; I’m a very happy iPhone user since day one of the Apple wireless revolution. This does not mean, though, that I can agree with a business strategy in which all of the other players in the mobile phone industry gang up on Google. (It is unclear were Nokia fits into all of this, but given the steadily decreasing share for its Symbian OS, I suspect the inclusion or not of Nokia will not be dispositive.)

The antitrust issue this presents is a thorny one, which frequently comes up in connection with trade associations and technical standards. When competitors collaborate, is under-inclusiveness or over-inclusiveness worse? Which is the bigger threat to competition? That is, if a trade group opens a collective buying consortium, for instance, is it better from an antitrust perspective to require that it be open to all — so that some rivals are not deprived of the scale economies — or that the consortium includes less than all firms in the market — so that competition in purchasing will drive down input prices?

Another concern is that, by excluding Google, the Rockstar consortium allows the other competitors to utilize the patents without paying license fees (since they now own them), leaving Google alone to need licenses for its Android OS. Does Nortel Patent Sale Make Google An Antitrust Victim? | TechFlash. That is a variant of “raising rivals’ costs” (here one rival only), which has over the past three decades become a recognized basis for assessing the anticompetitive nature of unilateral, single-firm conduct. When a group includes horizontal competitors who collectively control a huge share of the market, raising rivals’ costs supplies the anticompetitive “purpose or effect” needed to make out a rule of reason antitrust claim, even if the group boycott concern is misplaced or ameliorated. Here the intent to slow down Android is clear; whether that is anticompetitive, exclusionary or not is more ambiguous. Apple, Microsoft Patent Consortium Trying to Kill Android | eWeek.com.

There are precious few judicial decisions in this area and the IP licensing guidelines from DOJ/FTC do not really speak to the question. For that reason alone, the Rockstar Bidco venture, in my view, merits a very close look by the U.S. competition agencies. Allowing Google’s mobile phone competitors to do indirectly, with joint patent ownership, what they could not do indirectly, by agreeing not to license to Google, would be an incongruous result. On the other hand, a remedy may be worse than the harm. In standards, for example, it is often the case that antitrust risks are mitigated by requiring the holder of an essential patent to agree to so-called FRAND licensing (fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms and conditions). That’s an appropriate remedy where under-inclusiveness is the problem, so long as there’s a market measure for a “fair” license (royalty) price. Where the licensor, as in this instance, is everyone except the licensee, I for one fear there would be no objective way to assess whether license rates were reasonable.

DOJ's Christine Varney The lack of an effective remedy for a competition problem does not, of course, require that the transaction involved be blocked. At the same time, where a problem cannot be fixed, that is a good enforcement policy reason not to allow the structural market conditions giving rise to the issue in the first place. Put another way — a slight modification of an old aphorism — if there’s no remedy, maybe there should be no right. Whether the viability of the Rockstar consortium is decided by outgoing Assistant Attorney General Christine Varney or her September successor, the forthcoming answer should be interesting.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark office recently granted a patent to NetFlix for their online DVD ordering system. [NYTimes.com]. Now, I am a long-time NetFlix customer, but this indicates there’s a real problem in our patent system with the increasing issuance of so-called “business method patents.” Tim Hanrahan and Jason Fry write in Real Time for the Wall Street Journal that

The Internet bubble may have burst, but one of its unfortunate side effects is still with us, like a drunken partygoer who hasn’t noticed that a) it’s dawn, b) there’s no more beer and c) everyone else has gone home. . . . If you thought the [business-methods patent] controversy was as dead and buried as, say, IPOs for online pet-food delivery businesses, guess again. . . . Could someone — anyone — please grab Mr. Business Method Patent by the collar and heave him out in the hall so we can clean up?

Hear, hear!! It was bad enough with Amazon’s “one-click” patent, but now we’ve got insurance patents, order-processing patents and other patents for what are not inventions, but just ideas. Of course ideas are creative and deserve protection, but they should not be patentable. The difference is that copyright and trademark permit others to use creative ideas — within limits — to make better works, but patents are exclusive. It’s a difference of kind, and a crucial distinction between things that people actually build and things that they just dream of. Dreams are wonderful fantasies, as are business methods patents.

|

|