A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

Last month a Paris appeals court annulled some €3.9 million (US$5.2M) in fines imposed on endive producers and their trade associations by the French Competition Authority (the Autorité de la concurrence). Not dissuaded, that French competition agency just slapped a €1.6M (US$2.1M) fine on Caribbean yogurt maker Societe Nouvelle des Yaourts de Littee (SNYL) for falsely questioning the safety and quality of a rival brand in Martinique and Guadeloupe, characterizing the practice as “abuse of dominance” in the marketplace.

This epitomizes a fundamental disconnect between antitrust law and competition policy in the U.S. and that of many other nations. (No, the French are not alone…) American antitrust principles and decisions generally limit the reach of competition law — aside from competitor collision like price-fixing cartels — to business conduct that uses market power in an exclusionary manner. As the Supreme Court emphasized in 1993, “[e]ven an act of pure malice by one business competitor against another does not, without more, state a claim under the federal antitrust laws; those laws do not create a federal law of unfair competition or ‘purport to afford remedies for all torts committed by or against persons engaged in interstate commerce.'” In sharp contrast, the FCA reasoned about yogurt that “the dissemination of misleading and disparaging remarks by a dominant operator against one of its competitors is a serious practice with regard to competition rules.”

“Between December 2007 and December 2009, SNYL broadcast information discrediting the sanitary quality of Laiterie de Saint-Malo products using the questionable results of bacteriological tests and questioning the irregular consumption deadlines affixed to its products,” the FCA reported in a (translated) statement. This led a number of retailers to pull Malo products from shelves for an extended period. “This behavior had the effect of limiting product sales of Laiterie de Saint-Malo in Martinique and Guadeloupe — an abuse of dominant position prohibited by Article L 420-2 of the Commercial Code,” the FCA concluded.

In the United States, legal standards for proving antitrust claims are rightly rigorous; they are strict in order to reduce the risk that enforcement of the antitrust laws may chill the very sort of vigorous, competitive conduct they are intended to encourage. It’s been true forat least 35 years that the Sherman Act “is not a panacea for all evils that may infect business life.” Legendary antitrust law scholars Phillip Areeda and Herbert Hovenkamp have advocated a nearly insurmountable presumption against deception and fraud serving as the basis for a monopolization claim, a presumption most courts have readily embraced. As one court of appeals cogently explained, “[i]solated tortious activity alone does not constitute exclusionary conduct for purposes of a [Sherman Act] § 2 violation, absent a significant and more than a temporary effect on competition, and not merely on a competitor or customer…. Business torts will be violative of § 2 only in ‘rare gross cases.’”

The difference is that between competition and consumer protection, which are quite distinct concepts in American jurisprudence. If a firm uses a monopoly to harm competition without business justification, that’s an antitrust violation. If a firm lies about a competitor’s products or runs false advertising, that’s a deceptive business practice. The two legal regimes are directed at different constituencies and conduct, which is why the Federal Trade Commission Act was amended in the 1930s to add a separate provision (Section 5) for “unfair or deceptive” business practices, and why the FTC accordingly is separated into its two principal divisions: the Bureau of Competition and the Bureau of Consumer Protection. Likewise, the Lanham Act specifically prohibits false advertising and provides a damages remedy for injured companies. Thus, false representations around a firm’s own, or it’s competitor’s, products can be legally actionable, as the Supreme Court again ruled this year in a case about beverage labeling (Pom Wonderful v. Coca-Cola). They’re just not an antitrust violation in the United States.

Continue reading There Go the French Again On Competition

There’s a famous old political adage — “where you stand is where sit” (also known as Miles’ Law) — meaning basically that government policy positions are dictated more by agency imperative and institutional memory than objective consideration of the public interest. A related concept is “regulatory capture,” where administrative agencies over time become defenders of the status quo and pursue objectives more for regulated firms as their constituency than consumers. Capture theory is closely related to the “rent-seeking” and “political failure” theories developed by the public choice school of economics. Or as Harold Demsetz put it well in his influential 1968 article, Why Regulate Utilities?, “in utility industries, regulation has often been sought because of the inconvenience of competition.”

That’s no longer limited to electricity companies and other public utilities these days. With the advent of rapid, low-cost entry into previously sheltered markets, powered by technology and the sharing economy, today’s incumbent industries are taking regulatory capture and politics as rent seeking to new heights. At DisCo we’ve written extensively about Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Tesla and many other disruptive new start-ups that are facing a backlash from established industries (taxis, hotels and auto dealers, respectively) which use consumer protection as a Trojan Horse to disguise preventing or delaying competition on price, features and service. Politicians in locales as diverse as New York, New Jersey, San Antonio and Seattle (believe it or not!) have, wittingly it seems, gone along so far.

This is where what antitrust lawyers dub competition advocacy comes into play. Most antitrust policy in the U.S. is made in federal court as a result of merger, monopolization and horizontal collusion prosecutions launched by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). But due to our federal-state system and a judge-made doctrine allowing states to exempt some markets from competition despite federal antitrust demands (government action, and private conduct to obtain such action, is challengeable in only relative narrow circumstances), much of the battle takes place in the legislative and regulatory arenas. Accordingly, competition advocacy is the primary tool available to antitrust enforcers in the U.S. to oppose state and local regulations favoring established firms over start-ups and parochially sheltering in-state companies from out-of-state competitors. The result is that for three decades the federal antitrust agencies have engaged in affirmative outreach to state and local legislators and regulators in the form of comments, letters and occasional lawsuits that seek to drive home the basic truths that competition outperforms regulation and the law should not pick winners and losers when it comes to evolving markets. (State attorneys general also undertake competition advocacy, principally through amicus briefs, as well.)

Continue reading Competition Advocacy Matters—Here’s Why and How

Three high-level staffers at the Federal Trade Commission (Andy Gavil, Debbie Feinstein and Marty Gaynorare) are backing Tesla Motors Inc. in its ongoing fight to sell electric cars directly to consumers. As we’ve observed, Tesla forgoes traditional auto dealers in favor of its own retail showrooms. But that business model was recently banned by the New Jersey Motor Vehicle Commission — and is under fire in many other states as well — as a measure supposedly to protect consumers.

The ubiquitous state laws in question were originally put into place to prevent big automakers from establishing distribution monopolies that crowd out dealerships, which tend to be locally owned and family run. They were intended to promote market competition, in other words. But the FTC officials say they worry (as have we at DisCo) that the laws have instead become protectionist, walling off new innovation. “FTC staff have commented on similar efforts to bar new rivals and new business models in industries as varied as wine sales, taxis, and health care,” the officials write in their post. “How manufacturers choose to supply their products and services to consumers is just as much a function of competition as what they sell — and competition ultimately provides the best protections for consumers and the best chances for new businesses to develop and succeed. Our point has not been that new methods of sale are necessarily superior to the traditional methods — just that the determination should be made through the competitive process.” The ubiquitous state laws in question were originally put into place to prevent big automakers from establishing distribution monopolies that crowd out dealerships, which tend to be locally owned and family run. They were intended to promote market competition, in other words. But the FTC officials say they worry (as have we at DisCo) that the laws have instead become protectionist, walling off new innovation. “FTC staff have commented on similar efforts to bar new rivals and new business models in industries as varied as wine sales, taxis, and health care,” the officials write in their post. “How manufacturers choose to supply their products and services to consumers is just as much a function of competition as what they sell — and competition ultimately provides the best protections for consumers and the best chances for new businesses to develop and succeed. Our point has not been that new methods of sale are necessarily superior to the traditional methods — just that the determination should be made through the competitive process.”

As Tesla’s CEO Elon Musk noted earlier this year, “the auto dealer franchise laws were originally put in place for a just cause and are now being twisted to an unjust purpose.” Yes, indeed. It is pure rent seeking by obsolescent firms. State and local regulators have eliminated the direct purchasing option by taking steps to shelter existing middlemen from new competition. That’s not at all consumer protection, it is instead economic protectionism for a politically powerful constituency. Thanks to the FTC staff, some brave state legislators may now be emboldened to resist the temptation to decide how consumers should be permitted to buy cars.

Unfortunately, the issue is not limited to automobiles. I wrote recently about how in New York City, officials want to ban Airbnb because its apartment rental sharing service is not in compliance with hotel safety (and taxation) rules. The New York Times last Wednesday editorialized in support of that approach, arguing that Airbnb is reducing the supply of apartments and increasing rents. They’re wrong, of course, because short-term visits obviously do not substitute for years-long apartment leases. But the more important issue is that one economic problem does not justify reducing competition in a separate market. If New York actually has an apartment rent price problem, banning competition for hotels is no more a solution than prohibiting direct-to-consumer auto sales.

Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

The strangely named Rockstar Consortium has been in the news again, in part because some of its members just formed a new lobbying group, the Partnership for American Innovation, aimed at preventing the current political furor over patent trolls from bleeding into a general overhaul of the U.S. patent system. Yet Rockstar is perhaps the most aggressive patent troll out there today. Hence the mounting pressure in Washington, DC for the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division — which signed off on the initial formation of Rockstar two years ago — to open up a formal probe into the consortium’s patent assertion activities directed against rival tech firms, principally Google, Samsung and other Android device manufacturers.

Usually the fatal defect in antitrust claims of horizontal collusion is proving that competing firms acted in parallel fashion from mutual agreement rather than independent business judgment. In the case of Rockstar — a joint venture among nearly all smartphone platform providers except Google — that problem is not present because the entity itself exists only by agreement among its owner firms. The question for U.S. antitrust enforcers is thus the traditional substantive inquiry, under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, whether Rockstar’s conduct is unreasonably restrictive of competition.

Despite its cocky moniker, Rockstar is simply a corporate patent troll hatched by Google’s rivals, who collectively spent $4.5 billion ($2.5 billion from Apple alone) in 2012 to buy a trove of wireless-related patents out of bankruptcy from Nortel, the long-defunct Canadian telecom company. It is engaged in a zero-sum game of gotcha against the Android ecosystem. As Brian Kahin explained presciently on DisCo then, Rockstar is not about making money, it’s about raising costs for rivals — making strategic use of the patent system’s problems for competitive advantage. Creating or collaborating with trolls is a new game known as privateering, which allows big producing companies to do indirectly what they cannot do directly for fear of exposure to expensive counterclaims. Essentially, it’s patent trolling gone corporate. As another pro-patent lobbying group said at the time, Rockstar represents “a perfect example of a ‘patent troll’ — they bought the patents they did not invent and do not practice; and they bought it for litigation.” Predictiv’s Jonathan Low put it quite well in his The Lowdown blog:

The Rockstar consortium, perhaps more appropriately titled “crawled out from under a rock,” is using classic patent troll tactics since their own technologies and marketing strategies have fallen short in the face of the Android emergence as a global power. Those tactics are to buy patents in hopes of finding cause, however flimsy, to charge others for alleged violations of patents bought for this purpose. Rockstar calls this “privateering” in order to distance itself from the stench of patent trolling, but there are no discernible differences.

Continue reading Rockstar’s Patent Trolling Conspiracy

Every new year sees a slew of top 5 and top 10 lists looking backwards. Here’s one that looks forward, predicting the five biggest disruptive technologies and threatened industries for 2014.

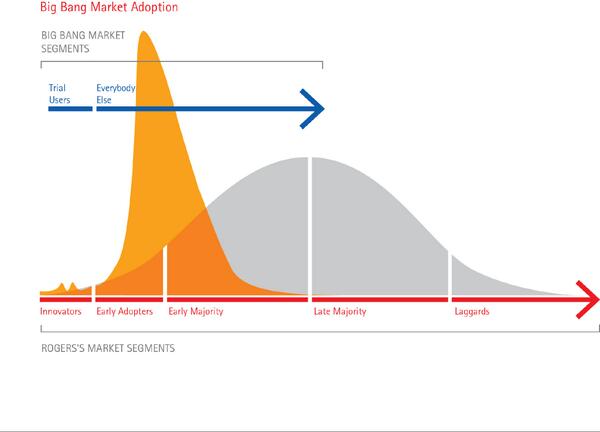

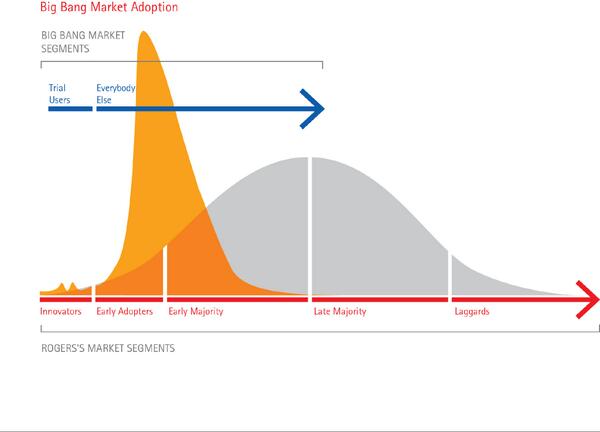

Making projections like these is really hard. Brilliant pundit Larry Downes titles his new book (co-authored with Paul Nunes) Big Bang Disruption: Strategy In an Age of Devastating Innovation. Its thesis is that with the advent of digital technology, entire product lines — indeed whole markets — can be rapidly obliterated as customers defect en masse and flock to a product that is better, cheaper, quicker, smaller, more personalized and convenient all at once.

Since adoption is increasingly all-at-once or never, saturation is reached much sooner in the life of a successful new product. So even those who launch these “Big Bang Disruptors” — new products and services that enter the market better and cheaper than established products seemingly overnight — need to prepare to scale down just as quickly as they scaled up, ready with their next disruptor (or to exit the market and take their assets to another industry).

Disruptors can come out of nowhere and happen so quickly and on such a large scale that it is hard to predict or defend against. “Sustainable advantage” is a concept alien to today’s technology markets. The reputation of the enterprise, aggregated customer bases, low-cost supply chains, access to capital and the like — all things that once gave an edge to incumbents — largely no longer exist or are equally available to far smaller upstarts. That’s extremely unsettling for business leaders because their function is no longer managing the present but inventing the future…all the time.

I certainly have no crystal ball. Yet just as makers of stand-alone vehicle GPS navigation devices were overwhelmed in 2013, suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere, by smartphone maps-app software, e.g., Google Maps, etc., so too do these iconic industries and services face a very real and immediate threat of big bang disruption this year.

Continue reading 5 Industries Facing Disruption In 2014

Despite the failures in recent years of such well-known retail chains as Circuit City, Borders and the like, it is way too soon to declare that the Internet will replace brick-and-mortar retailing. In part that is because consumer research suggests that in some segments, such as clothing, feeling and touching merchandise is an important part of the buying experience. Of interest to students of technological disruption, retailers are beginning in earnest to deploy technologies marrying the best aspects of online retailing with shopping malls and physical stores.

Delivery is one area where online retailers remain at a disadvantage. Amazon counters with its Prime membership for free two-day delivery, Amazon Lockers for local pick-up and its experimental foray into drone deliveries. Startups like Deliv (described as “a crowdsourced same-day delivery service for large national multichannel retailers”) are now providing equivalently fast store or home delivery for both online and in-person purchases.

Four of the nation’s largest mall operators are turning their properties into mini-distribution centers for rapid delivery, meaning shoppers can ditch their bags and keep spending. The service promises set delivery times for purchases consumers make at the mall or online from mall tenants, facilitated by a Silicon Valley start-up, Deliv Inc….The move highlights how delivery has become a key battleground in the war between physical and online retailers.

Startup Offers Same-Day Delivery at Shopping Malls | WSJ.com.

That in itself is remarkable. It shows that disruption is not a one-way street for legacy retailers. Yes, theirs is a challenging business environment, but technology is beginning to supply features for physical stores that meet and in some cases can beat online shopping providers. Home Depot, for instance, offers a smartphone app that allows consumers to check store inventory and aisle location, scan QR and UPC codes to get more information about products and order online with in-store delivery, overcoming some of the chain’s long-standing weaknesses: confusing layouts, out-of-stock merchandise and resulting abandoned visits.

Perhaps the most controversial realm is that of in-store consumer tracking and special offer distribution. This made news just last week when Apple Inc. turned on its iOS7 “iBeacon” service at its own retail stores. Macy’s has activated a shopkick-powered service through which simply walking into a Macy’s location will automatically send specialized offers to customers depending on where they are in the store. As Wired observed:

That’s just the beginning, though. Retailers are already talking about things like in-store navigation and dynamic pricing, all made possible by beacon-enhanced retail locations. For independent shops, iBeacon is a chance to jump into the smartphone era with one fell swoop. A $100 beacon is all it takes for even the mustiest book store to track customers, make recommendations, and offer discounts to customers’ pockets.

The risk, however, is that consumers may reject secret tracking technologies that retailers use internally, absent notice and consent. Over the last two years, retailers such as Nordstrom have hired software firms that gather Wi-Fi and Bluetooth signals emitted from smartphones to monitor shoppers’ movements around stores. They use the data to study things like wait times at the check-out line and how many people who browse actually make a purchase. At the prompting of Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) and the Washington, DC-based advocacy group Future of Privacy Forum, several location-tracking firms agreed in October to a code of conduct under which they will ask retailers to post signs in “conspicuous” spots in stores which inform consumers that their movements are being monitored and direct them to a website where they can opt-out. As Kashmir Hill noted in Forbes:

As with many novel and unexpected uses of technology, people have tended to be creeped out by the practice when they learn about it. Ask Path, which was tracking shoppers in malls (in 2011). Or Nordstrom, which came under fire earlier this year for tracking its shoppers without clear notice. Or London, which was using trash bins to collect info from passerbys’ mobile devices.

The flip side is that by offering recommendations and deals with an opt-in policy, retailers could dramatically bridge the divide between the online and brick-and-mortar experiences, making the latter still more like the former. Few consumers react negatively to Amazon or Netflix offering recommended products based on their past purchases. By doing the same thing in real-time, when a shopper passes the relevant store aisle or section, physical retailers would be in a position to offer something no e-commerce site can match: customized shopping with the ability to see, feel and take home impulse purchases enabled by technology.

There remain a slew of legal questions about whether the data collected by location-technology providers and retailers qualifies as personally identifiable data subject to the European Union Privacy Directive and the corresponding EU Safe Harbor in the U.S. In this country, it seems likely that the unique phone IDs associated with wireless devices — which are only linked to subscribers in the carrier’s switching and billing systems — would not be considered personal data by the Federal Trade Commission. In Europe, countries like the Netherlands and France have already articulated a more expansive view which could encompass device information in addition to name, address, phone numbers and the like. But even in the more liberal America, some have questioned whether retailers will be forced, whether by consumers or regulators, to dial-back autonomous tracking and adopt more transparent location practices.

All of this brings back memories for me personally. Nearly 15 years ago, I represented a start-up that was developing GPS chips for smartphones. While they are now ubiquitous (the start-up was sold to Qualcomm in March 2000), the challenges in making GPS work without a dedicated, external antenna were substantial. So like any good disruptor, my client went to the Federal Communications Commission to advocate cell phone location rules for E911 service that could give it a competitive advantage in the marketplace. The anecdote we used in our lobbying was that McDonald’s could message your phone, when passing one of its outlets, asking “Have you had your break today?” (That certainly dates the message, of course).

Technology has evolved so much that shopping is now almost at that place. Location tracking platform providers and their retail clients are offering a degree of interactivity never before available at retail. Whether it is compelling or creepy to consumers, of course, remains to be determined.

Note: The author has represented shopkick Inc., but not in connection with the company’s privacy policies and practices. Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

The U.S. economy has seen its share of disruptive technologies derailed (at least in time-to-market) by archaic legal regimes. Look to Uber’s taxi-hailing service and Airbnb’s apartment rental innovations as recent examples. Most times it’s a case of old assumptions about consumer protection and competition having lost validity with changed circumstances. Other times it’s simple protectionism by legacy incumbents, as in the legal assault on Aereo’s IPTV streaming service for alleged copyright infringement. In the case of electric auto developer Telsa Motors, however, it’s something a little different.

The problem for Tesla’s well-reviewed vehicles — Consumer Reports gave the new Tesla S its highest car rating ever — is not technical, as the California start-up boasts impressive lithium battery innovations and is aggressively building its own chain of recharging stations. Instead the constraint is a plethora of state laws (48 in all) that prohibit or limit automobile manufacturers from selling direct to consumers or owning auto dealerships. These statutes, which date to the 1950s, are matched by a federal law known as the “Automobile Dealers’ Day In Court Act.” That legislation is an anomaly which allows dealers (franchisees) to sue in their home federal district court and recover legal fees if a manufacturer fails to “act in good faith in performing or complying with any of the terms or provisions of the franchise, or in terminating, canceling or not renewing the franchise with said dealer.” (These sorts of lawsuits would otherwise require a minimum of $75,000 at stake, would be governed by state law and would not have the threat of fee-shifting.) The problem for Tesla’s well-reviewed vehicles — Consumer Reports gave the new Tesla S its highest car rating ever — is not technical, as the California start-up boasts impressive lithium battery innovations and is aggressively building its own chain of recharging stations. Instead the constraint is a plethora of state laws (48 in all) that prohibit or limit automobile manufacturers from selling direct to consumers or owning auto dealerships. These statutes, which date to the 1950s, are matched by a federal law known as the “Automobile Dealers’ Day In Court Act.” That legislation is an anomaly which allows dealers (franchisees) to sue in their home federal district court and recover legal fees if a manufacturer fails to “act in good faith in performing or complying with any of the terms or provisions of the franchise, or in terminating, canceling or not renewing the franchise with said dealer.” (These sorts of lawsuits would otherwise require a minimum of $75,000 at stake, would be governed by state law and would not have the threat of fee-shifting.)

Continue reading Want A Tesla? You Can’t Buy One Here.

Just a couple of weeks ago I put together a brief synopsis of the now-closed Federal Trade Commission (FTC) investigation of Google, Inc. for alleged monopolization, titled Deconstructing the FTC’s Google Investigation. To make the article fit within the space constraints of the American Bar Association’s Monopoly Matters newsletter, though, a few thoughts had to be edited out. One that is particularly appropriate now is the cogent observation by former FTC Chairman Jon Leibowitz that rivals frequently operate under the “mistaken belief” that criticizing the agency “will influence the outcome in other jurisdictions.”

Last Wednesday’s PR event by the FairSearch.org coalition made that evident in spades. We’ve discussed before that use of competition law to handicap other firms, rather than removing barriers to market competition, is unabashed protectionism, which can (perhaps should) backfire. The FairSearch companies continue to insist, as the coalition’s U.S. lawyer summarized, that the FTC “did not take on the issue of search bias.” That’s hogwash. The Commission found no evidence of harm to competition and, more importantly, rejected the FairSearch call for “regulating the intricacies of Google’s search engine algorithm.” And yet like Chicken Little, these companies continue to claim the sky is falling.

Leave aside for a moment that the FairSearch media event featured four legal presenters, all of whom are supporters of its lobbying positions, instead of a “fair and balanced” debate. And forget for a moment that the European Union’s parallel investigation (wrapped in much of the secrecy typical of an EU approach to competition regulation) is some 42 months old, with a possible end just recently within sight. What is most remarkable about the denial exhibited at the FairSearch media event is its blatant internal inconsistency. Three examples of the group’s positions make this abundantly clear.

- “Deception” Warrants a Disclosure Remedy. Former Assistant Attorney General Tom Barnett testified in 2011, for a founding FairSearch member, that Google acted anticompetitively because its “display of search results is deceptive to users.” FairSearch’s European counsel said the same thing recently, namely that Google “uses deceptive conduct to lockout competition in mobile.” But as I’ve noted previously, deception of this sort raises consumer protection issues, not legitimate antitrust concerns. Remarkably, Gary Reback scoffed at the reported suggestion by the EU’s Joaquin Almunia that a labeling remedy for Google’s revamped universal search results is appropriate, saying it’s “like telling McDonald’s customers they should eat healthy…it will not make a difference.” To the contrary, if deception is the problem then full disclosure has always been the answer. Where consumers are free to choose other search engines, and are told explicitly that some search results point to Google’s own “vertical” sites, whether they opt not to act is something about which competition authorities should be indifferent. Antitrust, at least in the United States, is not a Mayor Bloomberg-type vehicle for social engineering.

- Price Regulation Is Not the Job of Competition Enforcers. Ironically, the newest FairSearch approach raises the even more subtle antitrust issue of whether Google can be required to sell sponsored link ads to vertical rivals like Kayak and Yelp.

Known in competition parlance as a “unilateral refusal to deal,” the idea is that the remedy for Google’s preferential placement of its own services in organic search results should be a mandatory sale of ad space to purportedly “demoted” competitors. That’s hard to swallow under American antitrust doctrine, which makes unilateral refusal cases very difficult to win, described by the Supreme Court as the “outer limits” of the Sherman Act. More importantly, as Reback put it, the obligation would be to sell ad space on “reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms,” which in turn means that an enforcement agency or court would have to decide whether the ad rates charged by Google were “reasonable.” So while disclaiming an intention to create a federal search regulatory commission, the FairSearch companies are in fact doing just that. Even in price fixing cases, antitrust agencies and courts do not decide what a fair or reasonable price is, because they lack the ability to do so and because, after all, that’s the function of competition. Known in competition parlance as a “unilateral refusal to deal,” the idea is that the remedy for Google’s preferential placement of its own services in organic search results should be a mandatory sale of ad space to purportedly “demoted” competitors. That’s hard to swallow under American antitrust doctrine, which makes unilateral refusal cases very difficult to win, described by the Supreme Court as the “outer limits” of the Sherman Act. More importantly, as Reback put it, the obligation would be to sell ad space on “reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms,” which in turn means that an enforcement agency or court would have to decide whether the ad rates charged by Google were “reasonable.” So while disclaiming an intention to create a federal search regulatory commission, the FairSearch companies are in fact doing just that. Even in price fixing cases, antitrust agencies and courts do not decide what a fair or reasonable price is, because they lack the ability to do so and because, after all, that’s the function of competition.

- Mobile Really Is Different. The FairSearch event also included a competition lawyer for Nokia (Ms. Jenni Lukander), who contended that Google acted irrationally by giving away its Android mobile operating system, claiming the OS is merely a “Trojan Horse to monetize mobile markets.” So what? Providing free or open source software while profiting from ancillary products or services is a valid business strategy, pioneered by Netscape nearly 20 years ago and exemplified by Java, MySQL and numerous “freemium” sites such as Dropbox, Evernote, etc., available today. (This complaint is even stranger given that Nokia open-sourced its own mobile operating system in 2010, presumably for rational business reasons.) The FairSearch panelists argue that mobile is different because Google is supposedly “dominant” in mobile search, citing a market share of some 97%. That is both factually wrong and immaterial. Mobile is indeed different because Web search is rapidly being replaced by voice-search and app-based queries, which make any Google advantage in desktop search engines irrelevant. When Yelp gets nearby 50% of its traffic from its own smartphone app, it is impossible to seriously maintain that Google’s search engine is “diverting traffic” in the mobile space from rivals. Moreover, what the newest FairSearch complaint in Europe contends is that Google’s control over the Android OS limits OEM freedom by requiring some Google app icons (like the Google Play app store) to be displayed. As Dan Rowinski observed in readwrite mobile, that’s incorrect — “all kinds of stupid,” in his words. See Amazon’s locked-down Kindle, which runs Android without a single Google icon or app, as just one example. Most significantly, none of these vertical restrictions, even if they have the effect Nokia suggests, has any impact at all on search or search advertising in the mobile market. It is a fair conclusion that by venturing into the mobile OS arena, FairSearch is not looking for search fairness as much as to handicap and distract a rival with the threat of government regulation.

Here is how the New York Times summarized the new Android complaint by FairSearch.

The complaint was filed by Fairsearch Europe, a group of Google’s competitors, including the mobile phone maker Nokia and the software titan Microsoft, and by other companies, like Oracle. It accuses Google of using the Android software “as a deceptive way to build advantages for key Google apps in 70 percent of the smartphones shipped today,” said Thomas Vinje, the lead lawyer for Fairsearch Europe, referring to Android’s share of the smartphone market.

Any believer in the merits of competitive market economies must object to such misuse of competition laws. They should also, I suggest, react the same way to the most recent indication from Mr. Almunia that the EU’s purpose in investigating Google is to “guarantee that search results have the highest possible quality.” Nothing distills the difference between the European and American approaches to competition law as much as that revealing admission. Product quality is a function of the marketplace, not the government. And if regulation of search quality is deemed a subject warranting governmental regulation (which this author hopes never occurs), the one principle on which every objective observer would agree is that a regulatory scheme should apply uniformly to all firms in the market. That is plainly not what FairSearch strives to achieve, and thus why its proposals should be rejected by enforcement authorities worldwide.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

Given news that a European consortium of rivals has submitted yet another monopolization complaint against Google to the EU Commission, it is time to take stock of where we are in this long-running saga. A month ago the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) dropped its independent investigation, concluding that the facts did not support an antitrust prosecution of Google. Since then, the rhetoric from Google’s critics has reached absurd levels.

For instance, Bloomberg ran an editorial titled The FTC’s Missed Opportunity On Google. There the editors opined that “The FTC missed an opportunity to explore publicly one of the paramount questions of our day: is Google abusing its role as gatekeeper to the digital economy?” It is unfortunate that a leading American business publication could have so little understanding of competition policy and the role of antitrust law in policing the U.S. market economy. The editorial starts from an incorrect premise and proceeds to suggest, of all Luddite things, regulation of Internet search engines as “a public utility of sorts for e-commerce.” That’s obviously the theme of Google’s commercial rivals, but it’s neither correct nor appropriate.

Google’s alleged search dominance is hardly that of a gatekeeper. The fact is that Google neither acts like nor is sheltered from competition like the monopolists of the past, something the company’s critics never claim because they just can’t. Google succeeds only by running faster than its competitors. There’s nothing about Internet search that locks users into Google’s search engine or its many other products. Nor is new entry at all difficult. There are few, if any, scale economies in search and the acquisition of “big data” in today’s digital environment is relatively low cost, due to massively scalable storage architecture. Microsoft’s impressive growth of Bing in a mere three or so years shows that new competition in search can come at any time. Facebook’s recent, disruptive entry into search, leveraging its own trove of personalized user data, proves the point. As a result, Google remains surrounded by scores if not hundreds of competing providers of search, and succeeds relative to those rivals because its algorithms and search results are deemed superior (more accurate and useable) by Web patrons.

So what of this supposed “gatekeeper” role? North Korea is a gatekeeper to Internet content for its repressed citizens, but Google has none of that awesome economic and censorship power. If Google were really a search or Internet advertising monopolist, it would increase price like all classic monopolists, because monopoly power gives a firm the ability to do so. Yet Google search is a free product, supported by advertising. And that advertising is not priced by Google itself, rather through an auction among advertisers bidding on the use of search keywords. Google doesn’t control price, let alone raise prices. In fact, as its 2012 SEC filings admit, AdWords prices have fallen 15% in recent quarters.

The facts on the ground simply do not support the claim that Google’s search engine represents a bottleneck through which rivals must pass to gain website traffic. “Vertical” search competitors such as Yelp get nearly 50% of their traffic from smartphone apps, bypassing search engines, and thus Google, entirely. The only empirical data point supporting the Bloomberg thesis is that Web users tend to click much more on links displayed on the first or second pages of search results. But consumer inertia, lethargy or laziness doesn’t make Google itself any more powerful; and it certainly is no basis for antitrust intervention.

The call by the FTC to stay out of Internet search was a dispassionate end to a highly politicized investigation. Stripped of rhetoric, the Commission’s chairman, hardly a wallflower when it comes to aggressive enforcement, realized that the risk of transforming U.S. antitrust enforcers from prosecutors to regulators — something all knowledgeable antitrust lawyers regard as anathema — is very substantial in the area of Internet search. Search is inherently subjective, since its object is to produce results predicted to best satisfy a user’s interests. There is no objective standard against which to gauge the reliability, rank or relevance of Web sites in response to a search query. So putting Google under the antitrust lens for how it treats its own links versus so-called “organic” search results would embroil federal antitrusters in the Vietnam of Internet oversight, where ad hoc rules must be made up and the only way to “save” the search market would be to cripple the algorithms Google has used to make it the most popular search engine in the world. Further, treating Google as a public utility is nonsense in an era when even telephone and cable television companies, which have long-standing geographic exclusivities and control real bottleneck monopoly facilities, are no longer regulated as utilities.

Continue reading A Vietnam of Internet Regulation

Disintermediation is the heart of the Internet’s value proposition; cutting out the middleman in order to reduce distribution costs at scale. Now the first and best example of this point, Amazon.com, is quietly going a bit in the other direction.

According to a report Monday by Reuters, Amazon is installing “lockers” in 1,800 Staples office supply stores nationwide. These are not cloud-based digital content lockers, but instead large automated dispensing machines.

The Amazon lockers at Staples will allow online shoppers to have packages sent to the office supply chain’s stores. Amazon already has such storage units at grocery, convenience and drug stores, many of which stay open around the clock. Amazon.com Inc., the world’s largest Internet retailer, is trying to let customers avoid having to wait for ordered packages due to a missed delivery.

The reason for Amazon’s move, which Seattle-based GeekWire says was quietly launched a year ago, is not difficult to figure out. The “last 30 yards” are the most important part of its supply chain, for which Amazon largely relies on UPS. Yet as consumers, especially Americans, now spend little or no time at home during business hours, there is often no one available at the shipping address to receive packages. That makes the opportunity cost of buying from Amazon, namely the time required for delivery, higher than otherwise the case, in turn making alternatives such as Walmart, Apple and Best Buy in-store pick-up or RedBox DVD rental kiosks far more attractive to buyers. Marketing experts call this the “omnichannel” retail strategy, designed to prevent “showrooming.”

The irony is clear. A company born on the Web, one that essentially birthed the distinction between virtual and brick-and-mortar retailing, is making a big investment (including whatever undisclosed fees it will pay to Staples) in the very companies its business model threatens. While Apple’s retail stores may have been unexpected for a PC manufacturer, they represented an incremental change to the company’s distribution system. Amazon, in contrast, is moving stealthily into a new, mixed-mode business model that embraces part of the IRL retailing segment it once promised to make irrelevant.

Whether this will make a competitive difference remains to be seen. Consumers can now (literally) vote with their feet.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

|

|