A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

Even before the landmark United States v. Microsoft Corp. antitrust case, competition law was a bit schizophrenic when it came to the question of interoperability. Monopolists have no general duty to make their products work with those of competitors, but what about the situation where a dominant firm deliberately re-designs products to render them incompatible with others? That is the provocative question raised by several pending antitrust lawsuits filed against Green Mountain Coffee, manufacturer of the Keurig line of single-serve coffee makers and coffee “pod” products.

TreeHouse Foods alleged in a complaint last winter that after its patent on “K-Cups” expired in 2012, Green Mountain:

abused its dominance in the brewer market by coercing business partners at every level of the K-Cup distribution system to enter into anticompetitive agreements intended to unlawfully maintain Green Mountain’s monopoly over the markets in which K-Cups are sold. Even in the face of these exclusionary agreements that have unreasonably restrained competition, some companies, such as TreeHouse, have fought hard to win market share away from Green Mountain on the merits by offering innovative, quality products at substantially lower prices. In response, Green Mountain has announced a new anticompetitive plan to maintain its monopoly by redesigning its brewers to lock out competitors’ products. Such lock-out technology cannot be justified based on any purported consumer benefit, and Green Mountain itself has admitted that the lock-out technology is not essential for the new brewers’ function.

In the consolidated multi-district litigation that ensued, Green Mountain is specifically charged with designing a so-called “Keurig 2.0” brewer which features technology that allows it to detect whether a coffee cartridge is one of Keurig’s K-Cups or is made by a third party that does not have a licensing agreement with the company. The machine will not brew unlicensed coffee pods.

The federal court overseeing the MDL cases denied the plaintiffs’ motion for an injunction on procedural grounds in September, issuing an opinion which reasoned that commercial success of the “2.0” brewers was uncertain and that coffee competitors would still have open access to some 26 million Keurig “1.0” machines for several years. In other words, the court did not reach the merits of the monopolization claim against Green Mountain.

So where does that leave Keurig? As Ali Sternburg observed before revelations of its new 2.0 technology, Green Mountain’s prior 20 years of patent protection allowed the company to build a competitive advantage by “cultivating its brand (which likely involves trademark protection), honing its supply chain efficiencies, and generally maintaining its dominance due to having the first-mover advantage.” More than ten years before those patents first issued, moreover, the federal courts had ruled that new product introductions by monopoly firms — in one well-known instance, Kodak — would not be considered an antitrust violation because “a firm that pioneers new technology will often introduce the first of a new product type along with related, ancillary products that can only be utilized effectively with the newly developed technology.”

Continue reading K-Cups, Innovation and Interoperability

Nearly six months before this week’s reveal of iPhone 6 and the Apple Watch, the Wall Street Journal reported that Apple was in talks with Comcast Corp. about “teaming up for a streaming-television service that would use an Apple set-top box and get special treatment on Comcast’s cables to ensure it bypasses congestion on the Web.” For content, the product reportedly would not only offer users access to on-demand movies, TV programs and other apps, including games, but also live Comcast cable programming. This raises a serious question whether such an arrangement would represent a procompetitive development or instead further delay a languishing 20-year federal effort to create a commercially viable retail market for cable set-top boxes (“STBs”).

There are three sets of obstacles potentially standing in the way of this initiative. First are business issues associated with customer control. As commentary noted at the time:

Back in February it seemed both Comcast and DirecTV were reluctant to allow Apple to develop a system where customers logged in using their Apple credentials instead of their pay-TV accounts. The fundamental question of who gets to have the primary relationship with the customer has played prominently in Apple’s negotiations with magazine and newspaper publishers in the past, so it makes sense that the issue would pop up again in a different medium. Given that Comcast has been investing in its own advanced set-top boxes, the cable giant is probably not ready to cede too much ground too quickly.

The second set of issues relates to whether Apple, or any content provider, should be permitted to pay for routing of its IPTV traffic as a managed service, receiving priority handling for the packets involved, from ISPs. That is a subset of the network neutrality debate, commonly referred to as “paid prioritization,” that continues to rage before the FCC and Congress.

Yet a third set of issues has received scant attention in the business media. That is, how would an Apple STB deal with the 1996 legal mandate that so-called “navigation devices” be available for retail purchase by consumers, in other words unbundled from cable television and broadband service? Apple is known to have the most popular, addictive and tightly integrated ecosystem of all technology companies. The company is famous for steadfastly protecting this closed ecosystem and declining to make its hardware, or most software, interoperable with other platforms. The devices and software Apple sells are designed to work well with each other and sync easily so that preferences and media can be copied or shared with multiple devices without much effort. Applications work on many devices at the same time — even with a single purchase — and user interfaces are very similar across devices. Sure, out of necessity Apple offers iTunes software for Windows (supporting both the iTunes Store for music and video purchases and iPhone syncing on Windows PCs), but at their core most Apple products work best, if at all, only with other Apple products. Yet a third set of issues has received scant attention in the business media. That is, how would an Apple STB deal with the 1996 legal mandate that so-called “navigation devices” be available for retail purchase by consumers, in other words unbundled from cable television and broadband service? Apple is known to have the most popular, addictive and tightly integrated ecosystem of all technology companies. The company is famous for steadfastly protecting this closed ecosystem and declining to make its hardware, or most software, interoperable with other platforms. The devices and software Apple sells are designed to work well with each other and sync easily so that preferences and media can be copied or shared with multiple devices without much effort. Applications work on many devices at the same time — even with a single purchase — and user interfaces are very similar across devices. Sure, out of necessity Apple offers iTunes software for Windows (supporting both the iTunes Store for music and video purchases and iPhone syncing on Windows PCs), but at their core most Apple products work best, if at all, only with other Apple products.

As a business strategy, the closed Apple ecosystem experienced some very bad years in the mid-1990s, yet today has propelled Apple into its current status as the world’s most valuable corporation. As a legal and policy matter, though, things could be quite different.

Continue reading Apple’s Cable Set-Top Box and Interoperability

This is hilarious, and not altogether far-fetched. As the authors ask, wouldn’t it be interesting if Siri, the most famous example of artificial intelligence, had her deposition taken in litigation against Apple claiming the technology did not work as advertised?

Courtesy of my friends at Gallivan, White & Boyd, P.A. and their Abnormal Use blog. See also Lawsuit Claims Siri Doesn’t Know What She’s Talking About | Forbes.

While lots of bits and ink have been devoted to Apple Inc.’s well-publicized run-in with the Department of Justice over its role in a price-fixing conspiracy among e-book publishers, most of the media has not analyzed the array of private antitrust cases — mainly consumer class actions — brought against the iconic company. These typically allege that Apple’s closed ecosystem of iTunes, the iPod and iPhone are unlawful efforts to monopolize various media or hardware markets. After looking more closely at the merits of these various cases, I predicted in June that

the choice of a vertically integrated structure is unlikely to get Apple into antitrust trouble — either private or governmental, and whether in the United States or the EU — unless Tim Cook and company add some seriously bad acts to their competitive arsenal

Yesterday, a federal court of appeals (the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco) tossed one of the private antitrust class actions, which had challenged the lawfulness of the proprietary DRM technology Apple initially used for downloadable digital music, claiming the lack of interoperability inflated iTunes music prices. The court’s opinion concludes on procedural grounds that

under basic economic principles, increased competition — as Apple encountered in 2008 with the entrance of Amazon — generally lowers prices. See Leegin Creative Leather Prods. v. PSKS, Inc., 551 U.S. 877, 895 (2007); Barr Labs., Inc v. Abbott Labs., 978 F.2d 98, 109 (3d Cir. 1992). The fact that Apple continuously charged the same price for its music irrespective of the absence or presence of a competitor renders implausible [the plaintiffs’] conclusory assertion that Apple’s [DRM] software updates affected music prices.

I’m glad to have been right. More important, though, is one obvious point, which bears repeating: “On the pure antitrust merits, whether to pay off these class action plaintiffs is a decision Apple really should not have to make.” But as we say in the law, “deep pocket” defendants will always be put in that rather untenable position.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

Tech business news these days is dominated by headlines about the trial of United States v. Apple, Inc., where the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) is charging Cupertino with masterminding a massive conspiracy among publishers to increase prices for e-books. Apple’s defense lawyers and CEO Tim Cook call the allegations “bizarre.” What is really bizarre, though, is the plethora of private treble-damages lawsuits seeking to hold Apple liable under the antitrust laws for its vertical integration strategy with iTunes, iPhone and the App Store.

Just a bit more than a decade ago, Apple Computer (having since changed its corporate name) was decidedly stuck in the backwater of the PC industry. Its introduction of the USB-only iMac in 1998 failed to change the marketplace dynamics, where Apple’s closed Macintosh design and refusal to license its Mac OS to other manufacturers was viewed as the source of diminishing relevance. Apple was such a non-entity that its presence was flatly rejected by the federal courts as part of the relevant market in the Microsoft monopolization cases. Pundits predicted that like the fabled Betamax, Apple’s proprietary strategy would lead to its ultimate competitive demise.

But then along came the “iLife” software suite and the first generation iPod. What differentiated these products was not that Apple invented the technologies — after all, MP3s had been around for years and digital cameras as well — but rather that they all worked well together. Since then, the same business model has been applied to iPads and iPhones: native sync integrated with the Mac OS and Apple’s iCloud service, plus software content, whether media or apps, available easily through Apple’s online stores, with the company taking a 30% cut of retail prices for third-party content.

When the iPod and iPhone proved to be winners, big ones, Apple’s financial fortunes turned around dramatically. iTunes now is the largest digital music retailer, accounting for some 60% of all downloads, and the various iPhones are the most popular smartphones globally. Apple’s annual revenues soared from $5 billion in 2001 to $108 billion last year. But what short memories we have. The plaintiffs’ antitrust bar accuses Apple of unlawfully monopolizing these markets and has filed a series of sometimes confusing consumer class actions challenging Apple’s vertical integration and closed product systems. (Nine separate lawsuits have been unified into one action in California focusing on the tight grip Apple exerts on the iPhone’s services and applications; other individual and class suits are pending elsewhere.) The EU reportedly has investigated Apple’s App Store restrictions, and more recently its deals with European wireless carriers, to determine whether the company “abused” a “dominant position.” When the iPod and iPhone proved to be winners, big ones, Apple’s financial fortunes turned around dramatically. iTunes now is the largest digital music retailer, accounting for some 60% of all downloads, and the various iPhones are the most popular smartphones globally. Apple’s annual revenues soared from $5 billion in 2001 to $108 billion last year. But what short memories we have. The plaintiffs’ antitrust bar accuses Apple of unlawfully monopolizing these markets and has filed a series of sometimes confusing consumer class actions challenging Apple’s vertical integration and closed product systems. (Nine separate lawsuits have been unified into one action in California focusing on the tight grip Apple exerts on the iPhone’s services and applications; other individual and class suits are pending elsewhere.) The EU reportedly has investigated Apple’s App Store restrictions, and more recently its deals with European wireless carriers, to determine whether the company “abused” a “dominant position.”

Continue reading Five Reasons Apple’s Private Antitrust Risks Are Minimal

Disintermediation is the heart of the Internet’s value proposition; cutting out the middleman in order to reduce distribution costs at scale. Now the first and best example of this point, Amazon.com, is quietly going a bit in the other direction.

According to a report Monday by Reuters, Amazon is installing “lockers” in 1,800 Staples office supply stores nationwide. These are not cloud-based digital content lockers, but instead large automated dispensing machines.

The Amazon lockers at Staples will allow online shoppers to have packages sent to the office supply chain’s stores. Amazon already has such storage units at grocery, convenience and drug stores, many of which stay open around the clock. Amazon.com Inc., the world’s largest Internet retailer, is trying to let customers avoid having to wait for ordered packages due to a missed delivery.

The reason for Amazon’s move, which Seattle-based GeekWire says was quietly launched a year ago, is not difficult to figure out. The “last 30 yards” are the most important part of its supply chain, for which Amazon largely relies on UPS. Yet as consumers, especially Americans, now spend little or no time at home during business hours, there is often no one available at the shipping address to receive packages. That makes the opportunity cost of buying from Amazon, namely the time required for delivery, higher than otherwise the case, in turn making alternatives such as Walmart, Apple and Best Buy in-store pick-up or RedBox DVD rental kiosks far more attractive to buyers. Marketing experts call this the “omnichannel” retail strategy, designed to prevent “showrooming.”

The irony is clear. A company born on the Web, one that essentially birthed the distinction between virtual and brick-and-mortar retailing, is making a big investment (including whatever undisclosed fees it will pay to Staples) in the very companies its business model threatens. While Apple’s retail stores may have been unexpected for a PC manufacturer, they represented an incremental change to the company’s distribution system. Amazon, in contrast, is moving stealthily into a new, mixed-mode business model that embraces part of the IRL retailing segment it once promised to make irrelevant.

Whether this will make a competitive difference remains to be seen. Consumers can now (literally) vote with their feet.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

The week before last I participated in a conference on mobile payment technologies. I expected to find out more about Square and other startups that have begun to revolutionize credit card acceptance by solo businesses like food trucks. What I learned instead is that this nascent industry is way bigger than the emerging near-field communications (NFC) protocol Apple unexpectedly did not include in its new iPhone 5. More surprisingly, it seems the biggest attraction for inventors and investors isn’t the payment transactions themselves at all.

Some take-aways:

- A bunch of different technologies are competing at the standards/platform level for mobile payment processing. These include EMV, Isis and TSM, as well as NFC. A major driver in adoption is that new ventures are cutting deals with point-of-sale (POS) equipment vendors to integrate their protocols into the next software updates for these ubiquitous checkout devices. The biggest barrier to adoption is security and PCI compliance.

- Many of the largest U.S. retailers (7-Eleven, Walmart, Sears, Best Buy, etc.) have teamed up in a joint venture called MCX, which has yet to decide on a common approach to use of smartphones as payment devices. By virtue of their ubiquity, the MCX players may have the scale to make their selection of mobile payment technology an inflection point in this transformation.

- The advantage of mobile payments to retailers is not simply allowing consumers a convenient way to make purchases. Rather, it is the Holy Grail of demographic, time and location information allowing Location Based Marketing (LBM) in the “last three feet.” By capturing GPS-enabled location data, using wireless geofencing to engage in push/pull marketing interactions — think shopkick and the like (disclaimer: shopkick has been a client of mine) — and mining that data, mobile payment companies will know more about consumer preferences and behavior than SKU-level retailers or the major credit card processors like Visa and MasterCard.

This presents some interesting questions from a business and social perspective. Will and should the same liability approach used for traditional credit cards, quite protective of the consumer, apply where the credit card is essentially integrated into a smartphone? How will mobile POS (MPOS) technologies change the retail experience, for instance use of swipeable tablets by sales clerks for “line-busting” at peak sales hours?  Will consumers be more comfortable with non-persistent technologies that utilize one-off QR codes for payment authentication than the always on NFC payment “wallet” backed by Google? Given the shambles of our national financial regulatory system in the U.S. post-2008, which of the slew of federal agencies, from the Federal Reserve to the much-maligned CFPB, will have jurisdiction to regulate this new market, and what sort of regulation is appropriate? Will consumers be more comfortable with non-persistent technologies that utilize one-off QR codes for payment authentication than the always on NFC payment “wallet” backed by Google? Given the shambles of our national financial regulatory system in the U.S. post-2008, which of the slew of federal agencies, from the Federal Reserve to the much-maligned CFPB, will have jurisdiction to regulate this new market, and what sort of regulation is appropriate?

Several months ago I asked, only partially in jest, whether technology had finally made currency irrelevant. Mobile payment technologies are only in their infancy in America, which lags well behind Japan and the EU. But in light of the scale of the U.S. economy, what the markets do here can have a profound effect on financial practices worldwide. The problem is that because the American approach to data privacy and ownership — where the manufacturer or merchant owns the transactional records — is so different, the driver of MPOS innovation here may not translate well abroad. Jerry Maguire’s catch phrase must be refined a bit, because mobile payment innovation in the U.S. wants to be shown the data, not the money.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

A few weeks ago, the head of competition for the European Union, Joaquin Almunia, reportedly instructed Google that the search giant must make “sweeping changes” to its business model by extending restrictions the Europeans are insisting upon for Web search into the mobile realm. (See EU Orders Google to Change Mobile Services | Reuters.)

Is he possibly for real? We all know mobile is growing by leaps and bounds, powering political revolutions, connecting the developing world to the new information economy, and disrupting legacy industries. That market dynamism should instead counsel for a restrained approach, delaying government intervention until at least some of the dust settles, because mobile is different. Here’s why — and how that matters.

1. Apps Rule Mobile, Not Web Search

With more than 300,000 mobile applications released in the last year alone, “apps are increasingly replacing browsers as the method of choice for connected consumers to find and use information.”  This striking user preference is neither difficult to discern nor hard to understand. One can see it walking on nearly any downtown street as teenagers query Foursquare and Facebook apps for friend check-ins, businessmen find lunch spots with OpenTable or Yelp, and 20-somethings search for trending hashtag topics inside Twitter’s app. In other words, in the mobile realm apps rule. This striking user preference is neither difficult to discern nor hard to understand. One can see it walking on nearly any downtown street as teenagers query Foursquare and Facebook apps for friend check-ins, businessmen find lunch spots with OpenTable or Yelp, and 20-somethings search for trending hashtag topics inside Twitter’s app. In other words, in the mobile realm apps rule.

Wired’s editor-in-chief Chris Anderson in 2010, along with Square’s COO Keith Rabois in 2011, both predicted flatly that the Web is dying and mobile devices with dedicated apps are to blame. Apple’s Steve Jobs (watch his keynote) said it a bit more provocatively:

On a mobile device, search hasn’t happened. Search is not where it’s at. People aren’t searching on a mobile device like they do on the desktop. What is happening is they are spending all of their time in apps.

The numbers now prove that all three of these pundits were correct. As much as 50% of mobile search is happening in apps today. In March, a remarkably small 18.5% of all smartphone and tablet usage was in the browser; the rest was through apps. Nearly half of smartphone owners today shop using mobile apps. The international wireless association GSMA reported as far back as 2011 that second only to texting (and even more than actual calls), native apps comprise the highest level of smartphone activity. Yelp’s CEO Jeremy Stoppelman told Wall Street on August 2 that a majority of weekend searches now come in through its mobile app and that “by choosing the Yelp app people are bypassing search engines and consequently their engagement is higher.” Even venerable Craigslist is today battling mobile apps.

So mobile Web search is either dead or dying. That’s in part, as explained in the next bullet, because mobile users need, want and expect immediate answers, not a listing of URLs for browsing. Blue links just do not cut it anymore when users are mobile.

2. Search Is Local, Targeted and Interactive For Mobile Users

CNN Mobile’s VP Louis Gump, a mobile legend, says that every business must “start with the assumption that mobile is different.” Reflecting that difference, mobile sites typically include only the most crucial and time- and location-specific functions and features, while desktop Web sites contain a wide range of content and information. The reason is that mobile users are looking for local, immediate and interactive information.

Consider these stats —

-

Somewhere from 40% to 53% of all mobile searches are local. Coupled with GPS location detection, mobile users employ their devices to navigate and explore the world around them. Coffee anyone?

-

-

Our “information needs and habits” are different on mobile, reports TechCrunch, where users want “smaller bits of information quicker, usually calibrated to location.” The end result is a relationship between device owner and information which is far more personal, immediate and reciprocal in the mobile environment than on the desktop. Marketers know this and are working feverishly to engage their audiences using these new selling points. Mobile marketing is “immediate, personal and targeted to specific consumer groups” says Twitter marketing rockstar Shelly Kramer.

3. Voice As the Mobile UI Is a Game Changer

Along with everything from in-car services like Ford’s Microsoft-powered Sync and even TV remote controls, mobile UIs are evolving rapidly to offer the consistency that made the graphical UI (GUI) so important in evolution of the desktop PC. But in the mobile environment, voice is becoming the always-available common denominator as the size of devices and the desire (and legal need) for hands-free use limit the effectiveness even of touchscreens.

Using market leader Apple as our example again, as Frank Reed commented in Marketing Pilgrim,

Siri is definitely a form of search. It’s a request and answer mechanism that can do tasks outside of search (texts, emails, etc.) but when a user asks it for the closest Italian restaurant it is, in essence, a search engine. It is presenting what its backend calculations have decided are the best possible answers for the question asked by the iPhone user. Sounds exactly like Google’s function as a search engine, doesn’t it? Different delivery of a result set but it’s search.

Android users have a similar capability with Google Now, which has been called “more than just a new voice search application for Android; it’s also an indication of how Google will overhaul the user interface for its search products.” Consumers will soon see this same sort of voice interaction in mobile apps (powered by Nuance and others), on Windows phones and from well-funded voice search venture AskZiggy.

Voice is “the most revolutionary user interface in the history of technology,” according to Forbes. And it is all about search: search on steroids that is. As far as Google, the Mountain View company countered with a just-announced voice search app for the Apple iOS and interactive search results on its mobile Web properties. Whether Google can recapture the inventiveness in voice and mobile search that allowed its Web algorithms to dominate is open to serious question. Right now it’s rather desperately playing catch-up.

4. No One Has Yet Figured Out How To Monetize Mobile

Look closely at that graphic. Notice the dramatic difference between advertising spending and usage rates on mobile platforms compared to other media? That’s because no one has really figured out yet how to monetize mobile services. Social media darling Facebook — illustrated painfully by its revenue and stock price stumbles — for years has stood as the dominant supplier of display ads on the Web, but has just barely tried to introduce advertising into its mobile app. Considering that in May total usage of Facebook mobile surpassed that of its classic website for the first time and the clear lesson is that profiting from mobile information is a difficult endeavor, lagging well behind most technology markets.

Other than wireless network carriers, that is. As The Economist explains:

The [mobile] combination of personalisation, location and a willingness to pay makes all kinds of new business models possible….. Would-be providers of mobile Internet services cannot simply set up their servers and wait for the money to roll in, however, because the network operators — who know who and where the users are and control the billing system — hold all the cards.

This is not the place to discuss data caps and shared wireless plans, but the fact is that few if any mobile Internet services except those employing a pay-per-subscriber model have even come close to monetizing the mobile experience. That will and must change, although when and how remain unclear. As BusinessWeek notes, “desktop Internet use led to the rise of Google, eBay and Yahoo, but the mobile winners are still emerging.”

5. Mobile FIRST Is The New Reality

Ten, five or even two years ago, developers all talked about the need to adapt content to fit the smaller form factor, screen real estate and touch navigation features of mobile devices. That’s already ancient history today. The new reality is that everyone from television and media companies to PC manufacturers are thinking “mobile first,” designing interfaces (gesture-based and voice-powered), content (shorter, punchier and more micro blog-like) and interactivity (social media integration, video clip streams, etc.) to cater to an audience that is dominantly mobile, most of the time.

The title of Luke Wroblewski’s new book Mobile First says it all. In a mobile world, all we thought we had learned about the Web is reversed and upside down. Mobile starts from scratch and leads everything else.

So how do these profound differences matter? This author (and my Project DisCo colleague Dan O’Connor) has previously written about the difficulties of “market definition” in search, a big term for the simple idea that display ads, text ads and organic search results are all competing for the same customers. If the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which is still “investigating” Google for alleged search monopolization two years on, took this into account, its lawyers would scuttle any government prosecution because Google’s market share would be well below that of search alone, hardly in monopoly territory.

Earlier DisCo commented about the European Union’s penchant for regulating nascent products and industries before they even exist. By moving against Google in mobile Web search, the EU is instead trying to regulate a market that is dying and all but irrelevant to the realities of today’s mobile Internet usage and experience. With news just days ago that Americans spend more time watching their smartphones than watching television, the reality is that the mobile market may have already hit an important inflection point. In the name of protecting the future, however, Europeans are living in the past.

The FTC should pay attention. Mobile is different and poised to surpass fixed Internet usage. Whatever “gatekeeper” functions Google plays on desktop PCs (which we think is a huge overstatement), it is plainly not the same in the mobile realm. Let’s free the competitive battles to flourish in mobile search before government steps in with its thumb on the scale. In a mobile world, everything is different; those differences need to and should be reflected in antitrust enforcement policies.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

For all the discussion, dead-on accurate, about law holding back technological innovation, sometimes it works the other way around. When industries are transformed by disruptive new technologies and business models, the law itself can be in for a game-changing, forced makeover.

Take the European Union (EU) and digital music. Everyone by now realizes that the introduction of portable MP3 music players, coupled with Apple’s pioneering iPods and iTunes music store, have revolutionized the market for distribution of recorded music. Gone are the days of buying albums (or even CDs) just to get one hit song. Music is available on any device, in the cloud, streaming on desktops, and everywhere else, and it’s intensely personal playlists involved. As a result, the hockey stick adoption curve shows that hardly a decade after digital music downloads first gained popularity, “record stores” – Tower Records,

anyone? – are a thing of the past, record labels (EMI as the latest) appear to be on their last hurrahs, and fully 1/2 of all music

purchased in the United States is totally digital, never burned to a physical product.

That has not been the case in the EU. Despite a standard of living in excess of the US, less than 20% of music sold in Europe is digital. That’s in part because, under the EU Treaty, copyright licensing is conducted on a member state basis. This “balkanization” of the law (pun intended) means that digital sellers in the EU need to negotiate separate deals with each label and for each country, from France to the Czech Republic to Turkey, under very different legal regimes. That’s obviously a recipe for increasing costs and timeframes for entry, bad for business and keeping new distribution models from consumers. That has not been the case in the EU. Despite a standard of living in excess of the US, less than 20% of music sold in Europe is digital. That’s in part because, under the EU Treaty, copyright licensing is conducted on a member state basis. This “balkanization” of the law (pun intended) means that digital sellers in the EU need to negotiate separate deals with each label and for each country, from France to the Czech Republic to Turkey, under very different legal regimes. That’s obviously a recipe for increasing costs and timeframes for entry, bad for business and keeping new distribution models from consumers.

In response, the EU Commission used its competition powers a couple of years ago to harmonize copyright laws in order to make them consistent throughout the EU, aimed at breaking down national barriers in the digital music business and making it possible for rights holders to issue pan-European licenses. As one can observe from a similar step towards telecom “liberalisation” in the ‘00s, however, that itself requires a vigilant enforcer at the EU level to ensure that parochial national legislatures and courts do not slow roll the process. This 2008 licensing change helped Apple launch its iTunes music store in all 27 European nations, but so far no one else. In 2009, major members of the online music industry — including

Amazon, iTunes, EMI, Nokia, PRS for Music, Universal, and others — signed a pact with the European Commission to work towards wider music distribution in Europe.

Yet Apple remains the only digital music seller with licenses to operate in every EU country. And even then, Apple rolled out iTunes stores in Poland, Hungary and 10 other European countries just last year, seven full years after arriving in Germany, the UK and France. As ArsTechnica comments:

Unlike the US, online music in Europe is typically only sold through one country’s stores at a time — this is despite the EU’s efforts to effectively eliminate the borders of its 27-country membership when it comes to products and services. As such, if you’re in Spain and want to buy a song from France’s iTunes store, you can’t — the store blocks you from making the purchase because you aren’t in France. This has led to companies like Apple rolling out individual music stores for each European country with a large enough market, but the fragmentation has caused nothing but headaches for end users who just want to listen to their favorite music.

Finally—One iTunes Store to Rule Them All (in Europe).

The reality is therefore that the “single market” for intellectual property rights (IPR) contemplated in the EU’s 2011 report is far from ready to roll. As Neelie Kroes, who once took on Microsoft and now serves as the EU’s Vice President, asked rhetorically in ’08, “Why is it possible to buy a CD from an online retailer and have it shipped to anywhere in Europe, but it is not possible to buy the same music, by the same artist, as an electronic download with similar ease?”

So this week the EU is going a step further. Singling out “collecting societies” – European analogs to ASCAP and BMI which gather royalties of about €6 billion, or $7.5 billion, annually from radio stations, restaurants, bars and other music users and distribute the proceeds to authors, composers and other rights holders – the EU plans to push towards a directive requiring greater efficiency, transparency and reciprocity. Royalty-collection societies could be forced under the draft rules to transfer their revenue-gathering activities to rivals if they lack the technical capacity to license music to Internet services in multiple countries. The idea seems to be that if it cannot reduce the sheer number (some 250) of collecting societies, at least the European Commission can make sure they operate as much in unison as possible.

A lesson to be drawn from this ongoing saga is that just as technical innovation can disintermediate industries and eliminate arbitrage as an economic profit motive among different markets, so too can it work to force elimination of legal differences among jurisdictions. Especially where the medium is the Internet, inherently global and regulated by no one (unless the European-centric International Telecommunications Union has its way), these legal changes can occur very quickly. Believe it or not, the four years over which the EU has been working for digital copyright licensing harmonization is lightning pace for the law.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

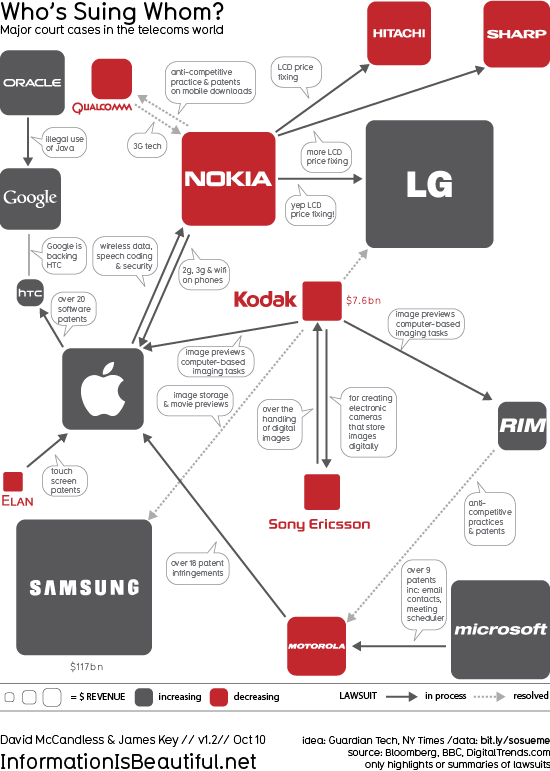

With reality television all the rage, viewers may wonder why there’s been no reality series about the inbred high-tech ecosystem of Silicon Valley. There should be, because the reality of how our technology bastion really competes today — namely by patent litigation and acquisitions — is astonishing.

Last year Google, Apple, Intel and other leading Silicon Valley companies were targeted by federal antitrust enforcers for tacitly agreeing not to hire each other’s key employees. Such a conspiracy could have landed top executives in jail. This year Apple, Samsung, Google, Nokia and others have all been battling over back-and-forth claims that smartphones and wireless tablets infringe each others’ U.S. patents. Now, just weeks after Google’s general counsel objected that patents are gumming up innovation, the search behemoth has announced its own $12.6 billion acquisition of Motorola Mobility, and with it their own portfolio of wireless patents, just a fortnight after purchasing a relatively few (“only” 1,000 or so ) wireless patents from IBM.

While the executives at Google have nothing to fear personally from these patent wars, others seem to have a lot at risk. That is because, according to the Wall Street Journal, the U.S. Justice Department’s Antitrust Division is investigating another possible conspiracy among Silicon Valley companies. This one arises out of the collective bid in the late spring of nearly every wireless phone operating system manufacturer, except Google, for a portfolio of 6,000 cell phone patents formerly held by bankrupt Canadian company Nortel. Simply put, Google started the bidding at about $1 billion, but the others joined forces to lift the price to an astounding $4.5 billion and win the prize.

That’s the legal background to Google’s just-announced Motorola Mobility acquisition, and it’s one that could have serious anticompetitive consequences. If the curiously named “Rockstar Bidco” consortium — which includes Microsoft, Apple, RIM, EMC, Ericsson and Sony — refuses to license the erstwhile Nortel patents to Google for its Android wireless operating system, they will be agreeing as “horizontal” competitors not to deal with a rival. Classically such group boycotts are treated as a serious antitrust no-no, and a criminal offense. If the group licenses the patents, on the other hand, they could be guilty of price fixing (also a possible criminal offense), since a common royalty price was not essential to the joint bid and would eliminate competition among the members for licensing fees.

If the Rockstar Bidco companies decide to enforce the patents by bringing infringement litigation against Google, things could be even worse. Patent suits themselves, unless totally bogus, are usually protected from antitrust liability so as not to deter legitimate protection of intellectual property assets. (That does not mean they’re competitively good, since patent suits are often just a means of keeping rivals out of the marketplace.) Nonetheless, a multi-plaintiff lawsuit by common owners of patents would have those same horizontal competitors agreeing on lots of joint conduct, well beyond mere license rates. For starters, is the objective of such an initiative to kill Android by impeding its market share expansion? That’s a valid competitive strategy, standing alone, for any one company; it takes on a totally different dimension when firms collectively controlling a dominant share of the market gang up on one specific rival.

Google’s broader complaint that patent litigation in the United States is too expensive, too uncertain and too long may well be right. This bigger issue is being debated in Washington, DC as part of what insiders call “patent reform.” The high-stakes competitive battles being waged today in the wireless space under the guise of esoteric patent law issues like “anticipation” by “prior art” suggest a thoroughly Machiavellian approach to the legal process, just as war is merely diplomacy by other means. They inevitably color the perspective of policy makers, who watch with regret as a system designed to foster innovation gets progressively buried with expensive suits, devious procedural maneuvering and legalized judicial blackmail.

Even the biggest companies, though, would find it hard to compete if their largest rivals were allowed to form a members-only club around essential technologies to which only they had access. Microsoft’s own general counsel countered two weeks ago that Google was invited to join an earlier consortium bid but declined before the Nortel auction. Embarrassing, yes; dispositive, no. If the offer were still open, now that it is clear Google’s principal wireless rivals are all members, things would be different. Indeed, there’s even an opposite problem of antitrust over-inclusiveness where patents and patent pools are concerned. If everyone in an industry shares joint ownership of the same basic inventions, where’s the innovation competition? Google’s defensive purchase of Motorola is a desperate, catch-up move that does not really change this “everyone-but-Android” reality.

Silicon Valley’s patent wars are for good reason not nearly as popular as Bridezillas or So You Think You Can Dance. Yet they are far more important, economically, to Americans addicted today to their smartphones and spending hundreds of dollars monthly on wireless apps and services. Whether the Justice Department will challenge the Rockstar Bidco consortium or give it a free pass remains to be seen. From a legal perspective, it is just a shame the subject is too arcane, and certainly way too dull, to make a reality TV series.

|

|