A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

When Google’s proposed acquisition of Motorola Mobility was announced in 2011, the business press focused mainly on the extension of Google’s core business from Internet search into hardware. But from a legal perspective, the treatment given the deal by competition authorities in the United States, the EU and China raises intriguing questions about the scope and objectives of merger policy in emerging technology markets.

The acquisition represents a classic case of downstream vertical integration into complementary markets. Since Google’s aborted launch of its own “Nexus One” smartphone in 2010, Google’s presence in the wireless handset and other hardware markets has been minimal. Merger reviews typically focus on horizontal concentration in a relevant product market; namely, to evaluate the risk that an increase of concentration post-transaction may produce a rise in prices or other so-called “coordinated effects.” There has been virtual unanimity among antitrust scholars and enforcement authorities for several decades that vertical integration typically presents little or no antitrust risk.

That is a principal result of the Chicago School antitrust revolution, ushered into American antitrust law and policy by GTE Sylvania in 1977. Under this approach, vertical restrictions and other relationships between manufacturers, distributors and retailers are presumptively procompetitive by increasing incentives for interbrand competition. Although technically classified as a “rule of reason” analysis, in reality the leniency of American antitrust law to vertical restraints has been such that there are almost no significant examples (with a few exceptions, like the Microsoft monopolization case of 1998-2000) of vertical restraints or mergers being judged to violate the Clayton Act or the Sherman Act.

So it should come as little surprise, therefore, that from an antitrust perspective Google’s proposal to acquire Motorola Mobility raised very few eyebrows. Yet just weeks ago it was announced that Google had received final approval to close the deal from the new China Competition Authority (the Ministry of Commerce, Anti-Monopoly Bureau ), contingent on one important concession. The Chinese required that Google pledge to maintain its Android operating system (OS) on a free basis for all wireless device manufacturers for the next five years.

The evident competition concern here is behavioral, not structural. That is, there is no risk that post-merger, Google’s share of either its own markets or Motorola’s markets will exacerbate coordinated affects or give it enhanced unilateral market power. To the contrary, the competitive risk potentially feared by antitrust regulators or competitors is that once it has a presence in wireless device manufacturing, Google might favor its own financial and competitive interests downstream by beginning to charge device manufacturing rivals for the Android OS.

This presents two provocative issues. First, should merger enforcement policy be grounded in a prediction of the post-transaction business incentives of the merging parties? While merger analysis must necessarily be based on a prediction of future effects, projecting the future business behavior of any one firm is far more problematic and unreliable than the kind of structural market analysis informed by HHI and oligopoly economics. And in most if not all antitrust regimes, even if the merger itself is accorded clearance by competition authorities, governments and competitors still have the opportunity to challenge actual post-merger conduct as a violation of the antitrust laws. Especially in rapidly changing technology markets — of which wireless handsets are undoubtedly a leading example — the risk of error in basing merger policy on predictions of future business behavior seems rather high.

The second issue raised by Chinese approval of the Google-Motorola deal is whether antitrust enforcers can or should dictate price. Typically, it is assumed that antitrust policy relies upon marketplace competition to produce the most efficient allocation of resources and “correct” pricing. Even in per se illegal price-fixing cases, the government never independently decides what the “right” price should be, but rather steps in to redress cartels or other restraints that limit the ability of market forces to set price based upon supply and demand.

“Open source” software, however, seems to be an emerging exception to that settled rule. In Oracle’s 2009 acquisition of Sun Microsystems, competitive concerns were raised about whether Oracle might begin charging for Sun’s open source mySQL database software. In Google’s 2010 acquisition of ITA, a travel software developer, the U.S. Justice Department required as part of a consent decree settlement that Google agree to maintain ITA pricing to travel service rivals and to continue R&D for the software itself. While ITA represents proprietary, paid software, the same vertical pricing concerns animated the government’s response to that deal as well.

But who is to decide whether an OS, or any other software, must or should be offered for free? The business model case for open source — dating back to that pioneered by Netscape in the late 1990s, where the Web upstart offered its browsing software for free in order to capture share and profits from the sale of server software — has been that companies offer free products in order to monetize their investment at another level (typically upstream) of the distribution chain. Economics would therefore teach that, if as seems correct, Google could make more money from handset profits than licenses for its Android OS, its rational business incentives would be to maintain Android as a free, open source product.

There’s still a big difference between legacy command-and-control economies like China, despite its recent liberalizations, and the market-oriented economy of the United States. Yet with increasing globalization these sorts of conflicting world views are likely to become more prominent. Whether the OS wants to be free could become less important than whether some government or enforcement agency – probably not in the U.S., one hopes – makes it their job to supplant the marketplace and dictate the answer.

Note: Originally written for my law firm’s Information Intersection blog.

Today Forbes published an op-ed article I wrote on the antitrust furor surrounding Google. Here’s the concluding paragraph:

Google doesn’t act like a monopolist and shares none of the characteristics sheltering classic monopolists from competition. Its astounding success in Internet search is universally regarded as a consequence of better design, superior code, better products and plain old hard work. Like Lewis Carroll’s other queen, the Queen of Hearts, Google really has no power at all. Just as the Alice in Wonderland queen could majestically dictate “off with their heads” with absolutely no effect, Google must continue to run faster simply to stay in the same place. That’s not a monopoly; instead it is a success story that should be applauded.

Off With Their Heads! The Fantasy Google Monopoly | Forbes.

The world of communications has been dominated for three decades, since United States v. AT&T, by a rather unusual confluence of antitrust and regulation. This has led to several noteworthy cases over the years addressing the interplay of the two regimes and whether the Communications Act overrides or immunizes certain communications companies or practices from antitrust scrutiny.

Luckily that’s been settled. In today’s environment, the consequence is that AT&T’s multi-billion dollar proposed acquisition of wireless rival T-Mobile will be reviewed both by the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division and the FCC. While there are some differences — DOJ must sue to block the deal, while affirmative FCC approval is required — the reality is that both agencies will apply similar competition analysis to the transaction.

That’s where things get a bit dicey. For one (although beyond the scope of this post), there’s been a long-running policy debate over whether FCC review and approval adds anything or is now redundant. More significantly, though, both DOJ and the FCC have shown a remarkable symmetry when it comes to “vertical” issues. That is, when competitive concerns arise from the relation between a firm and “downstream” rivals — for instance, as in AT&T, local and long-distance telephone providers — both agencies have increasingly opted for behavioral rather than structural remedies. (The latter go to the number and size of firms in a market, for instance by divestitures, while the latter direct the integrated post-merged firm what it can and cannot do in specified markets.)

Although the AT&T/T-Mobile deal has both horizontal and vertical elements, most media and analyst discussion to date has focused on direct competition for wireless subscribers, the classic horizontal concentration question. Regardless of the result there, observers can expect behavioral injunctions, whether by DOJ consent decree or FCC “conditions” to approval, addressing the deal’s vertical factors, for instance backhaul provided by landline telecom special access services and access to content (Web, television/video, etc.) from unaffiliated providers.

Behavioral conditions have been a growing feature of competition review in communications transactions in the U.S. for years, from AT&T/McCaw Cellular in 1993 to AOL/Time Warner in 2000 to Google-ITA earlier this year. Whether they work well, or not, is a different story for a different post. The record of their relevance and effectiveness is most decidedly mixed.

With reality television all the rage, viewers may wonder why there’s been no reality series about the inbred high-tech ecosystem of Silicon Valley. There should be, because the reality of how our technology bastion really competes today — namely by patent litigation and acquisitions — is astonishing.

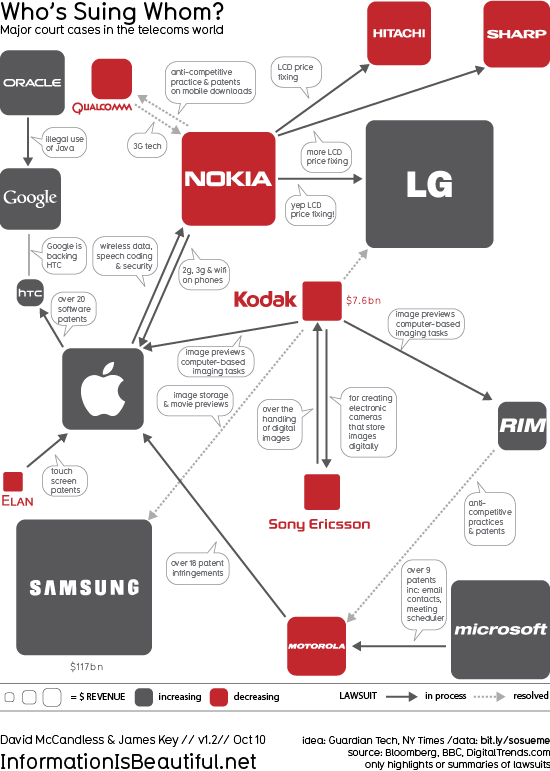

Last year Google, Apple, Intel and other leading Silicon Valley companies were targeted by federal antitrust enforcers for tacitly agreeing not to hire each other’s key employees. Such a conspiracy could have landed top executives in jail. This year Apple, Samsung, Google, Nokia and others have all been battling over back-and-forth claims that smartphones and wireless tablets infringe each others’ U.S. patents. Now, just weeks after Google’s general counsel objected that patents are gumming up innovation, the search behemoth has announced its own $12.6 billion acquisition of Motorola Mobility, and with it their own portfolio of wireless patents, just a fortnight after purchasing a relatively few (“only” 1,000 or so ) wireless patents from IBM.

While the executives at Google have nothing to fear personally from these patent wars, others seem to have a lot at risk. That is because, according to the Wall Street Journal, the U.S. Justice Department’s Antitrust Division is investigating another possible conspiracy among Silicon Valley companies. This one arises out of the collective bid in the late spring of nearly every wireless phone operating system manufacturer, except Google, for a portfolio of 6,000 cell phone patents formerly held by bankrupt Canadian company Nortel. Simply put, Google started the bidding at about $1 billion, but the others joined forces to lift the price to an astounding $4.5 billion and win the prize.

That’s the legal background to Google’s just-announced Motorola Mobility acquisition, and it’s one that could have serious anticompetitive consequences. If the curiously named “Rockstar Bidco” consortium — which includes Microsoft, Apple, RIM, EMC, Ericsson and Sony — refuses to license the erstwhile Nortel patents to Google for its Android wireless operating system, they will be agreeing as “horizontal” competitors not to deal with a rival. Classically such group boycotts are treated as a serious antitrust no-no, and a criminal offense. If the group licenses the patents, on the other hand, they could be guilty of price fixing (also a possible criminal offense), since a common royalty price was not essential to the joint bid and would eliminate competition among the members for licensing fees.

If the Rockstar Bidco companies decide to enforce the patents by bringing infringement litigation against Google, things could be even worse. Patent suits themselves, unless totally bogus, are usually protected from antitrust liability so as not to deter legitimate protection of intellectual property assets. (That does not mean they’re competitively good, since patent suits are often just a means of keeping rivals out of the marketplace.) Nonetheless, a multi-plaintiff lawsuit by common owners of patents would have those same horizontal competitors agreeing on lots of joint conduct, well beyond mere license rates. For starters, is the objective of such an initiative to kill Android by impeding its market share expansion? That’s a valid competitive strategy, standing alone, for any one company; it takes on a totally different dimension when firms collectively controlling a dominant share of the market gang up on one specific rival.

Google’s broader complaint that patent litigation in the United States is too expensive, too uncertain and too long may well be right. This bigger issue is being debated in Washington, DC as part of what insiders call “patent reform.” The high-stakes competitive battles being waged today in the wireless space under the guise of esoteric patent law issues like “anticipation” by “prior art” suggest a thoroughly Machiavellian approach to the legal process, just as war is merely diplomacy by other means. They inevitably color the perspective of policy makers, who watch with regret as a system designed to foster innovation gets progressively buried with expensive suits, devious procedural maneuvering and legalized judicial blackmail.

Even the biggest companies, though, would find it hard to compete if their largest rivals were allowed to form a members-only club around essential technologies to which only they had access. Microsoft’s own general counsel countered two weeks ago that Google was invited to join an earlier consortium bid but declined before the Nortel auction. Embarrassing, yes; dispositive, no. If the offer were still open, now that it is clear Google’s principal wireless rivals are all members, things would be different. Indeed, there’s even an opposite problem of antitrust over-inclusiveness where patents and patent pools are concerned. If everyone in an industry shares joint ownership of the same basic inventions, where’s the innovation competition? Google’s defensive purchase of Motorola is a desperate, catch-up move that does not really change this “everyone-but-Android” reality.

Silicon Valley’s patent wars are for good reason not nearly as popular as Bridezillas or So You Think You Can Dance. Yet they are far more important, economically, to Americans addicted today to their smartphones and spending hundreds of dollars monthly on wireless apps and services. Whether the Justice Department will challenge the Rockstar Bidco consortium or give it a free pass remains to be seen. From a legal perspective, it is just a shame the subject is too arcane, and certainly way too dull, to make a reality TV series.

The battle to beat Google’s Android mobile phone OS is quickly turning into a legal bonanza. Apple is suing HTC, Samsung and Motorola, all makers of wireless phones with the Android platform. Oracle is seeking up to $6.1 billion in a patent lawsuit against Google, alleging Android infringes Oracle’s Java patents. And Microsoft is suing Motorola over its Android line.

That’s all perfectly fine from an antitrust and competition standpoint — leaving aside the harder policy question of whether using patent infringement litigation to block competition should be permissible. Enforcing property rights is a legitimate and rational business activity that, absent “sham” lawsuits, is not second-guessed by antitrust enforcement agencies or courts. There can be exclusionary consequences, but they are a result of the patent laws in the first instance, not of themselves anything anticompetitive by the patent holder.

A much more troubling aspect of the increasing IP (or “IPR” as they say across the pond) battles surrounding Android is the recent sale of Nortel’s 6,000 or so wireless patents at a bankruptcy auction in Canada to a collection of bidders including Apple, Microsoft, RIM, EMC, Ericsson and Sony. How Apple Led The High-Stakes Patent Poker Win Against Google, Sealing Ballmer’s Promise | TechCrunch. The winning consortium bid more than $4.5 billion — some five times Google’s opening bid and, according to some pundits, far more than the portfolio was worth — to gain control of the patents.

“Why is the portfolio worth five times more to this group collectively than it is to Google?” said Robert Skitol, an antitrust lawyer at the Drinker Biddle firm. “Why are three horizontal competitors being allowed to collaborate and cooperate and join hands together in this, rather than competing against each other?”

Antitrust Officials Probing Sale of Patents to Google’s Rivals | Washington Post.

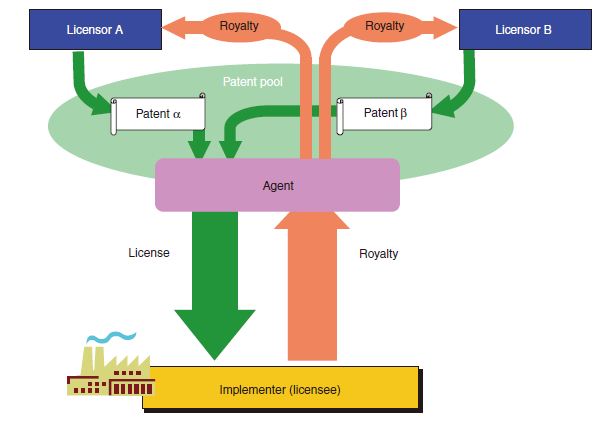

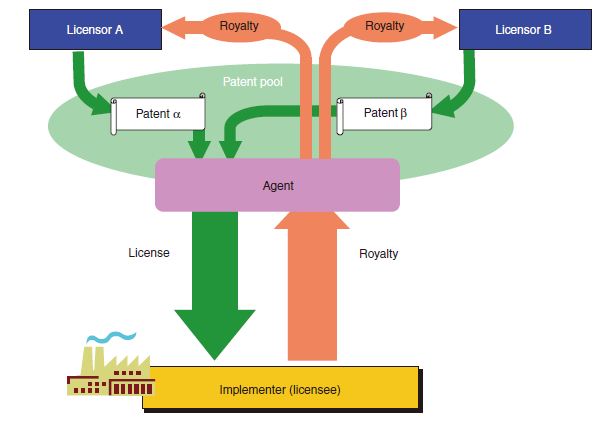

These are good questions. Patent “pools,” which are collections of horizontal competitors sharing patent licenses among themselves, are today generally considered procompetitive under the antitrust laws where they (a) are limited to technologically essential or “blocking” patents, and (b) do not contain ancillary restraints, such as resale price-setting or restrictions on participant use of alternative technologies. (MPEG, WiFi, LTE and other communications technologies are prime examples of patent pools.) The theory is that, with price effects eliminated, the cross-licensing of patents that might otherwise be used to block entry into a market reduces barriers to entry and increases efficiency.

Yet the consortium which won the Nortel wireless portfolio, revealing dubbed “Rockstar Bidco,” includes nearly everyone in the mobile phone and wireless OS businesses except Google. If these players agreed among themselves not to license their own patents to Google, that would be a per se illegal group boycott (also known as a concerted horizontal refusal to deal). Competitors cannot allocate markets or conspire to keep a rival out of the marketplace. It is unclear whether Google was invited to join Rockstar Bidco, but unless Larry, Sergey and Eric turned down such an offer, it seems a fair case can be made that the consortium bid was in effect an implicit horizontal agreement not to include Google. Post-auction, the reality of licenses will clearly tell us whether the joint ownership structure was a pretext to cover a refusal to deal. No one knows what the consortium intends to do with the Nortel patent portfolio; they won’t say. Microsoft, RIM And Partners Mum On Plans For Nortel Patents | Forbes. Yet the consortium which won the Nortel wireless portfolio, revealing dubbed “Rockstar Bidco,” includes nearly everyone in the mobile phone and wireless OS businesses except Google. If these players agreed among themselves not to license their own patents to Google, that would be a per se illegal group boycott (also known as a concerted horizontal refusal to deal). Competitors cannot allocate markets or conspire to keep a rival out of the marketplace. It is unclear whether Google was invited to join Rockstar Bidco, but unless Larry, Sergey and Eric turned down such an offer, it seems a fair case can be made that the consortium bid was in effect an implicit horizontal agreement not to include Google. Post-auction, the reality of licenses will clearly tell us whether the joint ownership structure was a pretext to cover a refusal to deal. No one knows what the consortium intends to do with the Nortel patent portfolio; they won’t say. Microsoft, RIM And Partners Mum On Plans For Nortel Patents | Forbes.

This author happens not to be a fan of Android; I’m a very happy iPhone user since day one of the Apple wireless revolution. This does not mean, though, that I can agree with a business strategy in which all of the other players in the mobile phone industry gang up on Google. (It is unclear were Nokia fits into all of this, but given the steadily decreasing share for its Symbian OS, I suspect the inclusion or not of Nokia will not be dispositive.)

The antitrust issue this presents is a thorny one, which frequently comes up in connection with trade associations and technical standards. When competitors collaborate, is under-inclusiveness or over-inclusiveness worse? Which is the bigger threat to competition? That is, if a trade group opens a collective buying consortium, for instance, is it better from an antitrust perspective to require that it be open to all — so that some rivals are not deprived of the scale economies — or that the consortium includes less than all firms in the market — so that competition in purchasing will drive down input prices?

Another concern is that, by excluding Google, the Rockstar consortium allows the other competitors to utilize the patents without paying license fees (since they now own them), leaving Google alone to need licenses for its Android OS. Does Nortel Patent Sale Make Google An Antitrust Victim? | TechFlash. That is a variant of “raising rivals’ costs” (here one rival only), which has over the past three decades become a recognized basis for assessing the anticompetitive nature of unilateral, single-firm conduct. When a group includes horizontal competitors who collectively control a huge share of the market, raising rivals’ costs supplies the anticompetitive “purpose or effect” needed to make out a rule of reason antitrust claim, even if the group boycott concern is misplaced or ameliorated. Here the intent to slow down Android is clear; whether that is anticompetitive, exclusionary or not is more ambiguous. Apple, Microsoft Patent Consortium Trying to Kill Android | eWeek.com.

There are precious few judicial decisions in this area and the IP licensing guidelines from DOJ/FTC do not really speak to the question. For that reason alone, the Rockstar Bidco venture, in my view, merits a very close look by the U.S. competition agencies. Allowing Google’s mobile phone competitors to do indirectly, with joint patent ownership, what they could not do indirectly, by agreeing not to license to Google, would be an incongruous result. On the other hand, a remedy may be worse than the harm. In standards, for example, it is often the case that antitrust risks are mitigated by requiring the holder of an essential patent to agree to so-called FRAND licensing (fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms and conditions). That’s an appropriate remedy where under-inclusiveness is the problem, so long as there’s a market measure for a “fair” license (royalty) price. Where the licensor, as in this instance, is everyone except the licensee, I for one fear there would be no objective way to assess whether license rates were reasonable.

DOJ's Christine Varney The lack of an effective remedy for a competition problem does not, of course, require that the transaction involved be blocked. At the same time, where a problem cannot be fixed, that is a good enforcement policy reason not to allow the structural market conditions giving rise to the issue in the first place. Put another way — a slight modification of an old aphorism — if there’s no remedy, maybe there should be no right. Whether the viability of the Rockstar consortium is decided by outgoing Assistant Attorney General Christine Varney or her September successor, the forthcoming answer should be interesting.

This post was written on December 1, but I decided then not to publish it because the accusation that I represent Google was made only in a small, relatively obscure Washington policy conference. Today, however, the New York Times reported that my law firm represents Google, a charge implicitly endorsed by lawyer Gary Reback, who called me Google’s “surrogate.” Round Two: Is Google a Monopoly? | NYT Dealbook.

So for clarity, allow me to reiterate the response I made — angrily, I admit, because I view attacks on one’s integrity as character assassination — a month ago. “I do not represent Google. My law firm does not represent Google. Google is not paying me.” I am not a surrogate for Google or any other company, organization or interest group. My views on net neutrality, for instance — which are very much in conflict with those of my clients Consumers Union and CCIA — demonstrate that when I speak, it’s because I have something to say, not because I am under the control of a client, or as Reback suggests, an undisclosed master.

The earlier post follows:

I attended a conference in early December about online privacy and Google — sponsored by ConsumerWatchdog.org — and was the victim of uncalled-for character assassination. When I dared to ask a critical question probing the validity of speakers’ assumption that Google is an unlawful Internet search monopolist, my question was met with the accusation that I am Google’s lawyer. That is simply not true.

It is a scurrilous allegation, first voiced two years ago by Microsoft, that appears intended to undermined the legitimacy of my views by ascribing them to a paying client. The reality, however, is that a simple review of court records would reveal that although Google was a former client — nearly a decade ago — since 2004 the law firms in which I was and am now a partner have been conflicted from representing Google because of litigation brought against the company. And these are not obscure cases, rather prominent ones challenging Google AdWords’ copyright policies and its age-related related employment practices. I have reiterated since 2008, when the issue was first raised, that I do not represent Google and my views on the Google-Yahoo! deal, the AdMob acquisition and the like are mine and mine alone. (See, for instance, my Oct. 2010 and April 2008 posts.) The descriptions on this site say explicitly that my clients “have over the years proudly comprised a veritable who’s who roster of the IT industry leadership,” including Google. Past tense, folks!

The tendency of Washington insiders to engage in ad hominem attacks on those voicing contrary views is reprehensible. I’ve gone the extra mile in the other direction, for instance pointing out that when Microsoft’s antitrust counsel-of-record filed massive suits against Google for small companies, “I don’t agree with guilt-by-association for lawyers in private practice.” To reiterate, neither Duane Morris LLP nor Glenn Manishin personally represent Google. Google does not pay for me to express my views. My law firms (past and present) do not count Google among their client roster. That I enjoy opining on matters of technology policy — such as net neutrality and “search neutrality” – does not mean that I am a shill for Google, Google’s allies, its partners and “ecosystem” or anyone else.

@ To reiterate, my law firm is adverse to Google, and neither I nor the firm represent the company. Thanks for your clarification!

So Gary Reback, Jeff Chester, John Simpson and others, get your facts straight. If my opinions are blather, rebut them on the merits. But do not attack the messenger because you disagree with his message. Especially when the accusation is clearly and demonstrably untrue.

P.S. In the Times, I said that Reback has a “vendetta” against Google. The Times editorialized that I was “taking a swipe” at Gary and “the claws are out.” But vendetta means a serious, long-running feud. As Reback has been going after Google for at least two years, since at least the Google book settlement, his position and public advocacy clearly qualify as a vendetta.

According to the New York Times, Texas attorney general Greg Abbott has launched an antitrust investigation of Google, based on the concept that deviations from “search neutrality” are anticompetitive and unlawful. Texas Attorney General Investigates Google Search | NYTimes.com.

The examination involves the fairness of Google search results, a concept called search neutrality. Some companies worry Google has the power to discriminate against them by lowering their links in search results or charging higher fees for their paid search ads.

This is utterly ridiculous. Google does not compete with the companies listed in its search results, but instead with other search engines for advertising. Anything Google may or may not do — and its mathematical algorithms leave precious little room for human bias — in Web search query results has no effect whatever on advertising competition. Search is by definition subjective because someone or something has to rank and order sites, but more importantly it is a free product. If anything, search bias would harm Google and help its search competitors (principally Microsoft-Yahoo!) by giving them a competitive advantage for search users looking for so-called “objective” Internet search results.

And in the only relevant market that counts — advertising — search neutrality is completely irrelevant. Even if advertisers pay for higher listings in search placement, as they can do for all Internet and search advertising (including “sponsored” or “promoted” search results on every major search site), that’s no different from paying for a full-page or inside front cover ad in a traditional magazine or newspaper. In the marketplace, that’s a completely acceptable, in fact desired, method of competition.

Now the search neutrality complainants argue that Google can “leverage” its search dominance into other markets. For instance, they say:

with its so-called Universal Search setup, Google is using its search engine monopoly — which controls an estimated 85 per cent of the global market — to unfairly favor its own services over those of its competitors. Universal Search transforms Google’s ostensibly neutral search engine into an immensely powerful marketing channel for Google’s other services. [I]t allows Google to leverage its search engine monopoly into virtually any field it chooses. Wherever it does so, competitors will be harmed, new entrants will be discouraged, and innovation will inevitably be suppressed.

Why the [EU] Google Antitrust Complaint is Not About Microsoft | The Register

As any antitrust lawyer knows full well, “leveraging” as a competitive concern is not unlawful and represents a discarded, 1960s-era theory of antitrust law. So this Texas investigation is really social policy (and bad policy, at that) on search engine technology masquerading as an antitrust issue. Get with it, A.G. Abbott, and be honest about what you are doing, which has nothing at all to do with competition or antitrust.

Even worse, if the Times’ sources are right, it seems that Microsoft itself, and my old antitrust colleague Rick Rule of Cadwalader, are behind the investigation.

The Texas attorney general has asked Google for more information on several companies, Google said. They include Foundem, a British shopping comparison site, SourceTool, a business search directory and myTriggers, which collects shopping links. In [a] Google blog post, [a company rep] drew an association to Microsoft. He said that Microsoft finances Foundem’s backer and that its antitrust attorneys represent the other two. Foundem is a member of the Initiative for a Competitive Online Marketplace, a European group co-founded and sponsored by Microsoft. SourceTool and myTriggers are clients of Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft, the law firm that represents Microsoft on antitrust issues.

Note also that Foundem runs the searchneutrality.org Web site.

I don’t agree with guilt-by-association for lawyers in private practice. But if Microsoft is financing these complaints, that just reinforces my long-held view that antitrust laws can be and frequently are used strategically to restrain competition and block rivals just as much as they can and should be used to pry open markets from dominance by monopolists.

You pick which motivation is at work here. My conclusion is obvious.

I’ll let my op-ed in Sunday’s San Jose Mercury News speak for itself. Opinion: In the Tech Industry, Small Isn’t Beautiful Anymore. Might be a little narcissistic to blog about one’s own article, no?

Wrangling over the proposed Google-Yahoo advertising deal makes one wonder whether scale, a virtue in Silicon Valley, can also be a vice. Some have insisted that Google is too big. But with apologies to economist E.F. Schumacher — author in 1973 of the generational anthem “Small Is Beautiful” — big isn’t bad anymore, it’s good.

A mere 10 years old, Google so dominates Internet search that the company’s name has become a verb. Google has grown large because it is good and its engineers continue to design innovative new products. That is something Web aficionados and antitrust regulators should applaud.

Google has already changed the way businesses advertise. The advertising issue is one its critics point to as evidence that Google is so large, the antitrust laws should kill the Google-Yahoo advertising venture before it launches later this month. The idea, as some ad agents have said, is that a combined Google-Yahoo share of “Internet search advertising inventory” would be competitively harmful. This is mushy reasoning being peddled to spread economic paranoia.

Everyone agrees that the principal objective of antitrust law is economic efficiency. To assess Google-Yahoo, therefore, one must first define what market we’re talking about. References to Internet search “inventory” are analytically dishonest, disguising the fact that search advertising — of which Google holds a 63 percent share — competes directly with Internet display advertising. Online display advertising is commanded by MySpace, AOL and Microsoft, and Google’s presence is tiny. As the data on rapidly declining advertising revenues for newspapers, network television and other “legacy” media reveal, Internet advertising is also becoming a substitute for advertiser dollars that used to flow elsewhere.

The consequence is that the relevant market cannot exclude Internet display advertising or even be limited to Internet advertising. And once the market covers something more than search ads, all serious competitive arguments against the Google-Yahoo transaction fade away. Take just a few.

Microsoft insists the alliance is unlawful price fixing because it will increase search advertising prices. To the contrary, neither Google nor Yahoo will be able to dictate minimum bids or prices to the other and, since advertisers will have a greater supply of more valuable search ads to buy — the demographically targeted ads produced with Google’s famously secret algorithms — the relative price for Internet search advertising will go down. That’s simple supply-and-demand, and it’s a good thing.

Others argue that Yahoo needs to remain independent and cannot be allowed into Google’s orbit. But this is not a merger or acquisition. If Yahoo’s board of directors, having just finished a bruising battle with Microsoft, violated its duty to maximize shareholder value, that is hardly the same as eliminating a competitor from the market.

Some suggest the government must act quickly to nip the growing power of Google in the bud. But in our market system we do not punish a successful company because it might do something bad in the future. Microsoft should be especially ashamed for endorsing this suggestion, since its decade-long antitrust fights here and in the EU arose from its bad acts, not its bigness. And unlike a merger, there can be no problem here of “unscrambling the egg” if things go south.

That leaves the only real objection to the Google-Yahoo! alliance as consumer privacy. There may be valid privacy objections to Google’s activities; indeed, Google might someday become so big that its possession of huge troves of personal data alone creates a threat to privacy. But as the FTC decided in approving the Google-DoubleClick merger in 2007, antitrust laws are not a substitute for privacy regulations.

So even here, privacy and bigness are not enemies. Unless Google starts acting badly in the competitive marketplace, the government should just leave it alone.

Glenn B. Manishin is an antitrust partner with Duane Morris in Washington, D.C. He was counsel for ProComp, CCIA and other software competitors challenging the Bush administration”s antitrust settlement with Microsoft. He wrote this article for the Mercury News.

Psystar claims Apple’s restrictions on third-party hardware makers violate U.S. antitrust laws. Mac Clone Maker Psystar Plans Antitrust Suit Against Apple [InformationWeek].

Woah, that’s absolutely ridiculous. A manufacturer cannot “monpolize” the market for its own products, and whether or not Apple’s refusal to license Mac OS X is a good business strategy, the Sherman Act permits it to keep the Mac a closed ecosystem. At least and until Apple’s market share of PCs get somewhere within lurking distance of Windows’ 90%+, there is no conceivable problem here. But like the iPod/iTunes “tying” cases — pending class actions filed last December — it is often and unfortunately more economic for a company to settled such bogus claims than to litigate them. Hope Apple shows some real backbone on this one!

Here’s another technology for which the adoption rate may be a decade longer than folks think — "cloud computing," like Google Apps. Google’s Right, but Cloud Computing’s Timeline Isn’t So Clear [Coop’s Corner]. Superb idea, but there are bandwidth, security, availability and reliability issues to be addressed before CIOs will adopt this model for the enterprise market. Already, however, it appears that the threat of this future, server-based computing architecture can be felt in today’s services and technologies.

|

|