A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

Nearly six months before this week’s reveal of iPhone 6 and the Apple Watch, the Wall Street Journal reported that Apple was in talks with Comcast Corp. about “teaming up for a streaming-television service that would use an Apple set-top box and get special treatment on Comcast’s cables to ensure it bypasses congestion on the Web.” For content, the product reportedly would not only offer users access to on-demand movies, TV programs and other apps, including games, but also live Comcast cable programming. This raises a serious question whether such an arrangement would represent a procompetitive development or instead further delay a languishing 20-year federal effort to create a commercially viable retail market for cable set-top boxes (“STBs”).

There are three sets of obstacles potentially standing in the way of this initiative. First are business issues associated with customer control. As commentary noted at the time:

Back in February it seemed both Comcast and DirecTV were reluctant to allow Apple to develop a system where customers logged in using their Apple credentials instead of their pay-TV accounts. The fundamental question of who gets to have the primary relationship with the customer has played prominently in Apple’s negotiations with magazine and newspaper publishers in the past, so it makes sense that the issue would pop up again in a different medium. Given that Comcast has been investing in its own advanced set-top boxes, the cable giant is probably not ready to cede too much ground too quickly.

The second set of issues relates to whether Apple, or any content provider, should be permitted to pay for routing of its IPTV traffic as a managed service, receiving priority handling for the packets involved, from ISPs. That is a subset of the network neutrality debate, commonly referred to as “paid prioritization,” that continues to rage before the FCC and Congress.

Yet a third set of issues has received scant attention in the business media. That is, how would an Apple STB deal with the 1996 legal mandate that so-called “navigation devices” be available for retail purchase by consumers, in other words unbundled from cable television and broadband service? Apple is known to have the most popular, addictive and tightly integrated ecosystem of all technology companies. The company is famous for steadfastly protecting this closed ecosystem and declining to make its hardware, or most software, interoperable with other platforms. The devices and software Apple sells are designed to work well with each other and sync easily so that preferences and media can be copied or shared with multiple devices without much effort. Applications work on many devices at the same time — even with a single purchase — and user interfaces are very similar across devices. Sure, out of necessity Apple offers iTunes software for Windows (supporting both the iTunes Store for music and video purchases and iPhone syncing on Windows PCs), but at their core most Apple products work best, if at all, only with other Apple products. Yet a third set of issues has received scant attention in the business media. That is, how would an Apple STB deal with the 1996 legal mandate that so-called “navigation devices” be available for retail purchase by consumers, in other words unbundled from cable television and broadband service? Apple is known to have the most popular, addictive and tightly integrated ecosystem of all technology companies. The company is famous for steadfastly protecting this closed ecosystem and declining to make its hardware, or most software, interoperable with other platforms. The devices and software Apple sells are designed to work well with each other and sync easily so that preferences and media can be copied or shared with multiple devices without much effort. Applications work on many devices at the same time — even with a single purchase — and user interfaces are very similar across devices. Sure, out of necessity Apple offers iTunes software for Windows (supporting both the iTunes Store for music and video purchases and iPhone syncing on Windows PCs), but at their core most Apple products work best, if at all, only with other Apple products.

As a business strategy, the closed Apple ecosystem experienced some very bad years in the mid-1990s, yet today has propelled Apple into its current status as the world’s most valuable corporation. As a legal and policy matter, though, things could be quite different.

Continue reading Apple’s Cable Set-Top Box and Interoperability

On behalf of the Sports Fans Coalition, I filed a brief yesterday with the FCC urging it to block the acquisition by Comcast Corp. of Time Warner Cable Inc. The gist of the argument is that the anticompetitive effects of vertical integration by cable systems have now reached crisis proportions with the ongoing refusal — already more than five months old and with no end in sight — of TWC to license Los Angeles Dodgers baseball games for cable or satellite distribution, or local broadcast, on any network other than its own SportsNet LA cable programming channel.

Hence this bold call for a remedy:

The Commission [should] hold the Applications in abeyance, declining to act all in this docket, unless and until TWC makes the SportsNet LA channel, and its exclusive Los Angeles Dodgers baseball content, available to all competing MVPDs at “fair market value and on non-discriminatory prices, terms and conditions,” and on the merits either (a) deny the Comcast-TWC request for transfer-of-control in its entirety, or (b) require the divestiture of all of Comcast’s RSN properties — sufficient for an independent competitor to operate the channels on profitable, going concern basis — as a condition to approving the acquisition of TWC.

Tuesday was a big day in the world of tech-powered disruptive innovation. What the news of April 22nd shows, however, is expanding use of the legal process by incumbent industries to thwart change — and the unfortunately all too frequent concurrence of regulators and courts with that ancient mantra of obsolescent businesses, namely “consumer protection.” Old, entrenched industries frequently lean on their political connections and get the government to come up with some new justification (or recycle an old one) for shutting down upstart rivals or, at the very least, undermining their competitive advantages.

Tuesday witnessed two potentially landmark events, ones that may in time change this familiar paradigm. The first was the morning hearing before the U.S. Supreme Court in ABC v. Aereo, the broadcast networks’ copyright law challenge to the now well-known streaming IPTV start-up. The second, just slightly later in the day, were oral arguments at a New York state court in Albany over whether Airbnb will be permitted to offer its peer-to-peer apartment rental services in New York City, where a 2010 measure meant to curb unregulated hotels prohibits renting out an apartment for less than a month.

The DisCo Project has devoted a series of posts to the Aereo case. Like a Sony Betamax for the 21st century, the Supreme Court is being asked to decide whether moving technology that is lawful for an individual to use on his or her own becomes a copyright violation if offered over the Internet. But the major broadcast networks (like the movie studios who opposed VCR recording in the 1980s) are convinced their entire business model will collapse if Aereo is sanctioned, threatening the nuclear option of stopping over-the-air transmission in favor of all-cable distribution should Aereo prevail.

Airbnb, in contrast, is fighting an effort by New York regulators to collect the names of Airbnb hosts who are breaking the law by renting out multiple properties for short periods. The company, which is now estimated to be worth $10 billion, is framing the dispute as a case of government scooping up more data than it needs for purposes that are vague. What the tussle is really about, of course, is whether the renting public actually needs protection from “unregulated hotels” and, even if true, why Airbnb’s efforts to make a market for DIY rentals is at all harmful. Continue reading Tech Tuesday: Litigation, Legislation and Regulatory Protectionism

Almost everyone realizes there is a federally managed “Do Not Call List” governing telephone marketers (or “telemarketers”). Less well known is that a 1991 law, the Telelephone Consumer Protection Act, 47 U.S.C. § 227, prohibits telemarketing calls using autoidialers without consent, unsolicited fax advertisements and telemarketing calls to cell phones. Combining this statute with class action procedures has resulted in some substantial damages judgments over the years.

The story of TCPA this year, though, is how the Supreme Court can sometimes see a legal issue so clearly despite confusion and conflicts among the lower federal courts. Earlier this term, the Court handed down a decision in Mims v. Arrow Financial Services LLC, in which it held that TCPA lawsuits can be brought in federal court pursuant to “federal question” jurisdiction. Although that same question had been answered in the negative by several courts of appeals — based on statutory language granting TCPA jurisdiction to state courts “if [such an action is] otherwise permitted by the laws or rules ofcourt of [that] state” — the Supreme Court’s decision was unanimous, 9-0, to the contrary. According to the Court’s opinion, since Congress had not divested federl courts of jurisdiction in the TCPA, state courts did not have excluisive jurisdiction over TCPA litigation because “the grant of jurisdiction to one court does not, of itself, imply that the jurisdiction is to be exclusive.”

There are some interesting themes of judicial temperment implicit in this holding, including a tendency (regardless of conservatism or political affiliation) for the federal judiciary to aggrandize its power despite constant reiteration of the concept of limited federal jurisdiction. What is remarkable about Mims, however, is more pragmatic. Even with the class action reforms of the past decade, federal courts still do a better job, especially for defendants, of administering nationwide class action cases. The Supreme Court has now given a green light to bringing these cases in federal district court. So the back-and-forth between federal and state court that has bedeviled TCPA litigants for years is now a thing of the past. Like the old Smith Barney commercials featuring John Houseman, when the Supreme Court talks, people listen.

Cross-posted from the Duane Morris Techlaw Blog.

This is the brief I just prepared for the Consumer Federation of America to the U.S. Supreme Court on the issue of whether the so-called Red Lion doctrine of First Amendment regulation of broadcasters should be re-examined. My favorite passage is:

[T]he presumption of invalidity inherent in petitioners’ argument is flawed. Broadcasters do not remain “singularly constrained,” Pet. at 16, on the ground that there were few speakers 45 years ago. When Red Lion was decided there were hundreds more newspapers in America, half a dozen or more in major cities like New York, national, weekly news and cultural magazines (Life, Look, etc.) and many other sources of information and entertainment that are no longer available in today’s marketplace. Therefore, the “undeniably large increase in the number of broadcast stations and other media outlets” on which the D.C. Circuit and petitioners rely, id. at 18, is immaterial to the economic regulation of broadcast licensees unless — as petitioners dare not suggest, because it is untrue — the increase has lessened the technical need for governmental entry and interference regulation.

Whether there are three or six or ten television stations in a local market, however, does not at all mean there is enough spectrum to accommodate everyone who would like to use the airwaves. What some judges have called “the indefensible notion of spectrum scarcity,” Action For Children?’s Television v. FCC, 105 F.3d 723, 724 n.2 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (Edwards, J., dissenting), is therefore totally true and completely defensible.

[slideshare id=11925599&doc=11-696cfaopp-brief-120308132113-phpapp02&type=d]

The world of communications has been dominated for three decades, since United States v. AT&T, by a rather unusual confluence of antitrust and regulation. This has led to several noteworthy cases over the years addressing the interplay of the two regimes and whether the Communications Act overrides or immunizes certain communications companies or practices from antitrust scrutiny.

Luckily that’s been settled. In today’s environment, the consequence is that AT&T’s multi-billion dollar proposed acquisition of wireless rival T-Mobile will be reviewed both by the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division and the FCC. While there are some differences — DOJ must sue to block the deal, while affirmative FCC approval is required — the reality is that both agencies will apply similar competition analysis to the transaction.

That’s where things get a bit dicey. For one (although beyond the scope of this post), there’s been a long-running policy debate over whether FCC review and approval adds anything or is now redundant. More significantly, though, both DOJ and the FCC have shown a remarkable symmetry when it comes to “vertical” issues. That is, when competitive concerns arise from the relation between a firm and “downstream” rivals — for instance, as in AT&T, local and long-distance telephone providers — both agencies have increasingly opted for behavioral rather than structural remedies. (The latter go to the number and size of firms in a market, for instance by divestitures, while the latter direct the integrated post-merged firm what it can and cannot do in specified markets.)

Although the AT&T/T-Mobile deal has both horizontal and vertical elements, most media and analyst discussion to date has focused on direct competition for wireless subscribers, the classic horizontal concentration question. Regardless of the result there, observers can expect behavioral injunctions, whether by DOJ consent decree or FCC “conditions” to approval, addressing the deal’s vertical factors, for instance backhaul provided by landline telecom special access services and access to content (Web, television/video, etc.) from unaffiliated providers.

Behavioral conditions have been a growing feature of competition review in communications transactions in the U.S. for years, from AT&T/McCaw Cellular in 1993 to AOL/Time Warner in 2000 to Google-ITA earlier this year. Whether they work well, or not, is a different story for a different post. The record of their relevance and effectiveness is most decidedly mixed.

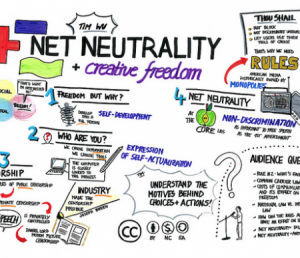

The news today is all about Tuesday’s “open meeting” at the FCC, where at long last a proposed regime for network neutrality will formally be considered. “There are of course a lot of moving pieces surrounding this debate, and however the chips fall, it’s going to have a long-term affect over how the Internet operates over the next several years.” The FCC Votes on Net Neutrality Tomorrow; The Internet Waits | AllThingsD.

Actually, the modest few rules FCC Chairman Genachowski has proposed are so trivial that, like all good policy, compromises or settlements, they have angered both the left and the right. The former deplores the scheme as worse than nothing, while the latter says it is a slippery slope to full regulation of the Internet.

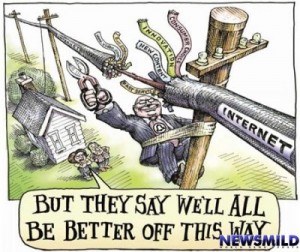

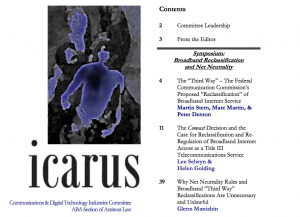

The far more important issue tomorrow is the legal framework under which the FCC will propose net neutrality rules. After the Comcast decision in April of this year — in which a federal court of appeals threw out the Commission’s decision to sanction undisclosed throttling of P2P traffic by ISPs — net neutrality has been in a state of extreme jurisdictional chaos. For an overview, read the Fall 2010 edition of the ABA’s Icarus magazine, a symposium issue on so-called “Title II reclassification” featuring, among others, this author.

About a month ago, Genachowski also announced has was abandoning his Third Way reclassification approach. That’s a brilliant decision, as reclassification was doomed to judicial reversal and, almost certainly, an injunction or stay against implementation. The alternative is for the FCC to articulate the ancillary jurisdiction linkage or nexus between the agency’s specific areas of delegated responsibility — telephony (Title II) and broadcasting (Title III) — and its general authority over “communications by wire or radio.” Yet to do that the agency needs to distance itself from the protectionist roots and core of the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, which for 40+ years has been used principally to squelch or constrain new technologies in order to prevent market competition with older, established industries (constituencies).

Here’s what I wrote earlier:

Ancillary jurisdiction under Southwestern Cable represents the low-water mark of communications jurisprudence. It was fashioned as a legal matter to permit FCC control of CATV, the infant predecessor to today’s robust cable programming industry, as a means of protecting the Commission’s power to regulate broadcast television. . . . It was protectionism to the core [and] epitomizes the conservative critique of administrative agencies as regulatory capture.

There is no longer an appetite in Congress to utilize governmental regulation to protect incumbents and vested commercial interests against competition and new entry. Hence, because it lacked and still lacks the political will to justify net neutrality on the ground of protecting its Title II and III jurisdiction over telephony and broadcasting — by sheltering the legacy providers of those services against disintermediation — the agency can never provide the requisite “nexus” demanded by the Comcast opinion.

Since no current policy or political figure today can admit to using regulation to handicap new entrants and favor established business interests, ancillary jurisdiction will remain the dark, dirty secret of administrative law until it is moved to a new footing. Imagine if the FCC reasoned that with IP convergence, services that formerly were within its Communications Act authority, like telephony and television, are increasingly moving to an Internet-based delivery system that, if it continues, will eventually leave all of communications beyond the FCC’s jurisdiction. Under this approach, the Commission could demonstrate a clear nexus between its statutorily delegated responsibilities and the ancillary role it proposes for net neutrality, without reverting to the sullied, protectionist past of ancillary jurisdiction.

Some observers may argue that such a “Title I” approach to net neutrality does not in principle prevent the FCC from exercising unlimited power over Internet communications. That’s overstated in my view. First, the Supreme Court’s 1970s decisions on ancillary jurisdiction (Midwest Video) hold that ancillary jurisdiction us not “unbounded.” Second, from a legislative perspective it is obvious that an administrative agency acting on the basis essentially of implied power cannot do anything broader under a general “public interest” standard than it could if acting under the express jurisdiction delegated by Congress. Specifically, while Title II authorizes full, rate-of-return common carrier regulation, the FCC would overstep its bounds imposing parallel rules under Title I ancillary jurisdiction. Third, the extreme critique from conservatives that agencies cannot be permitted to do anything without express congressional authorization really doesn’t apply; Congress has granted Title I authority over all interstate communications, it just has not fleshed that out with detailed standards.

More problematic are current reports that the FCC is considering relying on Section 706 of the Act, which urges the agency to promote “advanced telecommunications” services, as its ancillary jurisdiction hook for net neutrality. That’s inane, because the Commission in the 1990s ruled over and over again that 706 was not a basis for regulatory power. This means that using 706 as the nexus for ancillary jurisdiction will necessarily stoke a hotter fight over the FCC’s reversal of its statutory interpretation, a double whammy.

The better linkage is to the basic legislative commands (e.g., Section 201) that direct the FCC to ensure just and reasonable communications and broadcasting services for users. It cannot be disputed that if current trends continue, VoIP and Internet video could and well may eventually displace POTS and cable/broadcasting, in which case there would be nothing left with which the FCC could fulfill these elementary responsibilities if such IP-based services, which do not represent “telecommunications,” “cablecasting” or “broadcasting” in traditional statutory terms, must remain forever and completely unregulated.

A broader and more cogent question is, if the FCC takes this approach, would that not create a system in which an agency decides for itself how far to go when Congress fails to update its underlying statutory power to reflect technological change? Yes, it would. But it would not be Genachowski or the FCC creating this paradigm, it was the Supreme Court. A better legal system would have an administrative agency go back to Congress and ask for new powers if its old ones are being end-run by technology. As a practical matter, that could lead to gridlock, however, as in the communications arena general revisions of the Communications Act of 1934 happen very rarely — once in 65 years, far less than every generation.

So if politics is the art of the possible, it is possible for the FCC this Tuesday to make history, survive a judicial challenge and move archaic regulatory jurisprudence forward into a new era, stripped of its protectionist past. It’s also possible the Commission will be split politically, that left-wing proponents can convince some members that a principled loss is better than a compromise win, see Net Neutrality Supporters Question FCC’s Genachowski Plan | Techworld.com, or that as it has so many times in the past, the agency will fail to explain itself in simple terms the courts demand and can understand.

The Third Way of Title II reclassification was too cute for its own good. The Commission has a chance to correct that overreaching, but its internal bureaucratic tendencies to ambiguity and a “Chinese menu” theme for jurisdiction threaten to blow up net neutrality again. GOP Opposition to FCC Net Neutrality Plan Mounts | enterprisenetworkingplanet.com. Far more principled, regardless of one’s position on the substantive merits and policy need for network neutrality, would be for the FCC to pick a single, simple nexus. It’s not cute, it’s not expansive, but it would work. The question is whether in this highly polarized legal and political environment, the players really want anything to work at all.

Politics is always, in part, theater and sausage-making. That the law and public policy are the byproducts of such superficial pursuits remains a frustration, but in the United States it’s one we all have to live with, and one some pundits are convinced preserves the republican tradition of limited government. I for one hope the FCC keeps a more modest agenda tomorrow and moves the net neutrality debate closer to a conclusion, instead of adding fuel to the legal and policy fires that have raged on this issue for years.

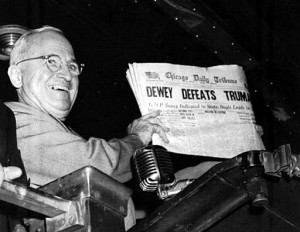

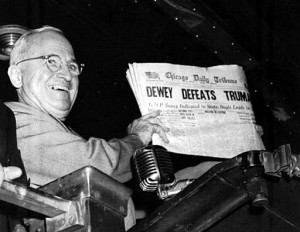

60 years ago, when Harry Truman beat Tom Dewey for the presidency, it was widely predicted by pollsters that Truman would lose. This led to the famous “Dewey Beats Truman” headline in the newspaper proudy flashed by the winning candidate.

The problem, it was later revealed, was that the Gallup organization based its poll results on responses to telephone inquiries. But in the late 1940s, that selection inevitably favored wealthier Republicans, leading to skewed poll results.

Gallup is best known for that one half-century-old blunder. There’s a terrible irony in that. The studious George Gallup did more than anyone to put opinion polling on solid ground.

We have a similar problem today, it appears to me. While telephone subscribership has now become ubiquitous, increasingly many citizens — especially twenty-somethings — no longer use landline telephones, instead going completely wireless. The proportion was 1 in 6 three years ago and continues to increase steadily. Pollsters, however, still base their surveys on landline phone subscribers. In fact, under FCC regulations it is unlawful to telephone a wireless subscriber for a “solicitation” or using an autodialer (a technical prerequisite to modern polling) without either their consent or a prior business relationship. Therefore, despite a non-profit exemption in the FCC’s rules (which, unlike the Federal Trade Commission’s “telemarketing sales rule,” do not expressly exempt political polling), the law is standing in the way of accurate political predictions.

How this will play out in next Tuesday’s elections is unclear to me, as I claim no special expertise in political punditry. But it is revealing that the problems experienced in 1948 are recurring today in a different form due to technological change and the accelerating proliferation of wireless communications devices.

This is the opening paragraph of an article by this author appearing today in the Fall 2010 issue of Icarus, the newsletter of the ABA’s Communications & Digital Technology Industries Committee, Section of Antitrust Law. “If the issue of broadband reclassification is not addressed with sensitivity to the history and traditions of FCC common carrier regulation, one can all too easily arrive at conclusions that simply cannot be squared with the legal framework applied to telecommunications for more than 30 years.”

The highly polarized debate over so-called net neutrality at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) exposes serious philosophical differences about the appropriate role of government in managing technological change. Neither side is unfortunately free either from hyperbole or fear-mongering. And neither side is completely right.

Read the whole essay. It’s provocative.

Note: I have not appeared as counsel for any party to the FCC’s current net neutrality NOI proceeding and was not paid to write this essay (despite what my colleagues and clients in the public interest community may claim). I represented Google in the past but now am ethically precluded from doing so because my law firm has a conflict of interest, being adverse to Google in an employment age discrimination case before the California Supreme Court. The article nonetheless does not reflect the views or opinions of my firm or any of my clients, past or present.

In a decision that has already generated a huge volume of commentary and predictions,1/ just three days ago the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit reversed a contentious ruling by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) from 2008 that penalized Comcast Corp. for violating the Commission’s “network neutrality” Internet principles. Comcast Corp. v. FCC, No. 08-1291 (D.C. Cir. April 6, 2010). Those principles include a content access requirement that the FCC said prohibited broadband operators and other Internet Service Providers (ISPs) from using network management practices to block or “throttle” specific Internet Protocol (IP) based services, such as the peer-to-peer, or P2P, filing-sharing communications offered by BitTorrent.

The Court’s opinion represents a devastating blow to the FCC’s assertion of ancillary jurisdiction authority over the Internet, ISPs and IP-based services. It calls into question how, if at all, the agency can implement many of the proposals put forward in its recent National Broadband Plan (NBP) and the “open Internet” proceeding launched last fall to codify those 2005 net neutrality principles (plus two additional rules proposed by new FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski). And the D.C. Circuit decision calls out for resolution by Congress of the jurisdictional void created — a call some legislators have already heeded.2/

Yet much of this crisis mentality appears unwarranted. There are accepted legal bases the FCC could employ to achieve a substantial part of its objectives related to consumer protection on the Internet. Where the FCC may not by statute operate, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) — which for several years has been biting at the bit to oversee broadband competition and consumer protection — can. That is because the Comcast decision compels the conclusion, at the very least, that broadband is not a “common carrier” service over which the FCC enjoys exclusive federal jurisdiction. The FCC’s proposal in its recent broadband plan that the agency apply universal service funds to subsidize broadband deployment in rural areas is likely not threatened materially by the Comcast decision. And the larger public policy fight over so-called “reclassification” of broadband as a Title II service presupposes, incorrectly, that Title II treatment means subjecting IP-based services to the same, traditional public utility model of regulation as monopoly telephone providers. In short, the agency and Congress face a dizzying array of alternatives and options. Yet much of this crisis mentality appears unwarranted. There are accepted legal bases the FCC could employ to achieve a substantial part of its objectives related to consumer protection on the Internet. Where the FCC may not by statute operate, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) — which for several years has been biting at the bit to oversee broadband competition and consumer protection — can. That is because the Comcast decision compels the conclusion, at the very least, that broadband is not a “common carrier” service over which the FCC enjoys exclusive federal jurisdiction. The FCC’s proposal in its recent broadband plan that the agency apply universal service funds to subsidize broadband deployment in rural areas is likely not threatened materially by the Comcast decision. And the larger public policy fight over so-called “reclassification” of broadband as a Title II service presupposes, incorrectly, that Title II treatment means subjecting IP-based services to the same, traditional public utility model of regulation as monopoly telephone providers. In short, the agency and Congress face a dizzying array of alternatives and options.

This post has two parts:

- First, I review the proceedings leading up to and the substance of Circuit Judge David S. Tatel’s opinion for a unanimous three-judge panel of the court of appeals.

- Second, I put the decision into context and explore ways in which the FCC could react, including the legal rationale(s) the agency would need to develop on remand.

Both portions of the essay, however, are of necessity general overviews. A complete examination of this rather wonk-ish area of communications jurisprudence requires a longer treatise than warranted for such a time-sensitive post. I encourage readers to address these issues in greater detail in comments below and to the FCC in its open Internet NPRM proceeding.

1. The Comcast Decision

The FCC had classified cable modem service as an information service under the bifurcated regulatory approach of Computer II and the 1996 Telecommunications Act, a ruling affirmed by the by the Supreme Court in NCTA v. Brand X, 545 U.S. 967 (2005). Nonetheless, the Commission later developed a set of four network neutrality principles adopted in a 2005 “policy statement.” These were intended to protect what the agency perceived as a threat to the open character of the Internet if vertically integrated content providers blocked or discriminated against other Web sites and content in order to favor their own IP-based services.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

Much like the assumptions underlying the NBP, the net neutrality principles aspired to an Internet free of any provider’s control, giving every end user access — with little or no permissible differentiation among services or even packets — to all content available anywhere, anytime. (They also harkened to a similar failed effort by public interest advocates, in the late 1990s, for what was then termed “cable open access.”)

Whether or not regulatory intervention is needed to ensure this result was not at issue in the Comcast appeal, but it was central to the FCC’s enforcement action that triggered the case. Faced with the reality that file-sharing end users were consuming huge amounts of bandwidth, Comcast deliberately limited their ability to use P2P client-side applications by first outright blocking, and later imposing network management controls on, BitTorrent IP traffic, so that the latency-sensitive applications of the majority of its Internet customers would be delivered uninterrupted. Some consumer advocates alleged that the cable giant did so in order to protect its own on-demand video programming services from potential competition. Comcast stopped the practice after the story came out but was later discovered to have misled the Commission with its initial responses, and the company never revealed to customers that some IP traffic was not being routed with the same throughput as other services. The FCC subsequently imposed reporting and disclosure requirements on Comcast’s traffic management practices, based on the 2005 policy statement, which the agency had not promulgated as actual rules or regulations.

Comcast appealed that decision. The FCC defended its actions on the ground that, even though Internet broadband is not a telecommunications service subject to Title II of the Act, the agency has ancillary jurisdiction to regulate. That ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, sometimes confusingly referred to as “Title I jurisdiction,” is based on a 1960s-era decision by the Supreme Court in which the FCC had restricted cable television by regulation in order to protect traditional TV broadcasters, over which the agency enjoyed express statutory authority. In Comcast, the D.C. Circuit concluded that under that approach, ancillary regulations must be ancillary to something explicit in the Act, in other words that the Commission must show that its traffic management directive was “reasonably ancillary to the … effective performance of its statutorily mandated responsibilities.” Finding that the FCC had not done so, the Court reversed.

Without detailing each of the statutory hooks advanced by the Commission, it suffices to say that the agency did not seriously urge the court of appeals to sustain ancillary Internet regulation in order to protect its Title II, III (broadcasting) or VI (cable) jurisdiction over legacy services for which the Communications Act grants explicit regulatory authority. Instead the FCC urged that various general statements of public policy appearing in the 1996 Act amendments provided the necessary linkage. The D.C. Circuit rejected that contention, concluding that policy does not suffice under the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine as a statutorily mandated responsibility. The FCC also cited section 706 of the 1996 Act, which directs it to “encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans.” The Court likewise rejected that linkage because the Commission itself had long ago ruled that section 706 does not constitute “an independent grant of authority” to the agency.

These holdings, foreshadowed earlier by oral argument — see “Appeals Court Unfriendly To FCC’s Internet Slap At Comcast” [Wall Street Journal] — are relatively unsurprising. What is somewhat unusual is that, in its appellate positions, the FCC suggested additional grounds for an ancillary jurisdiction theory that had not been relied on in its 2008 order. The most cogent of these added rationales was that Internet openness and nondiscrimination is ancillary to the “just and reasonable practices” mandate of sections 201(b) and 202(a), applicable to telecom carriers. Judge Tatel’s opinion dismissed these post-hoc justifications not on the substance, but rather because Administrative Procedure Act precedent requires a reviewing federal court to sustain or reverse a regulatory order on the same grounds offered by the agency in its underlying decision.

Comcast’s challenge of the 2008 order had offered the Court the opportunity to overturn it on the narrower ground that principles, unlike rules, are not enforceable in company-specific adjudications. But the D.C. Circuit did not reach that question. Its analysis essentially concurred with dissenting Commissioner Robert McDowell’s criticism that “[u]nder the analysis set forth in the order, the FCC apparently can do anything so long as it frames its actions in terms of promoting the Internet or broadband deployment.”3/

The end result is that the FCC’s network neutrality principles are effectively dead, for now at least. The agency has various options available, but unless and until it develops either an alternative rationale under its existing statutory framework, or procures a new legislative grant of authority from Congress, it cannot police the practices of ISPs and broadband providers. It is to these alternatives and their viability that I now turn.

2. The Post-Comcast Regulatory & Legislative Environment

In the wake of the D.C. Circuit’s decision, network neutrality advocates urged the FCC to ensure Internet openness by “reclassifying” broadband as Title II telecom service. Gloating opponents opined that the FCC was properly chastised and should rein in its efforts to regulate what they view as an increasingly competitive market, in which most major ISPs have long ago pledged to respect net openness as a business matter. Meanwhile, Web-based grassroots campaigns, with typical rhetorical excesses, sprang up overnight to “save Internet freedom.”

The reality is somewhere in between. Had the FCC desired, it could have — and still might — justify its ancillary jurisdiction by articulating a relationship between broadband Internet access and traditional, regulated communications services. By declining to review the Obama Commission’s arguments based on the mandatory obligations of reasonable rates and practices under Title II, the court of appeals has all but begged the FCC to do so on remand. The problem with this approach, especially given the history of the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, is that it reflects a paternalistic, corporate welfare model of economic regulation which is out of favor as a policy matter with politicians, regardless of their party affiliation or ideology.

It would not, however, require much in the way of legislation to give the FCC explicit authority to adopt and impose network neutrality nondiscrimination rules. In its 2009 stimulus legislation, Congress allocated $7.2 billion for distribution by executive branch agencies in the form of grants to spur broadband deployment. A portion of those funds was expressly conditioned on grantees’ agreement in advance to comply with the Commission’s 2005 network neutrality principles. Unlike broader calls to completely rewrite the Communications Act in light of convergence, a legislative “fix” specific to net neutrality would not be unusually difficult. Whether there exists the political will and votes to do so, especially in the aftermath of the divisive healthcare reform debate, is unclear.

Nor does the Comcast decision by the D.C. Circuit necessarily spell the death knell for the Commission’s National Broadband Plan. Some of its proposals, such as privacy protections for broadband end users and truth-in-billing disclosure requirements for ISPs, would surely require new legislative authority. Yet the basic objectives of the plan, including its proposal to allocate an additional $16 billion in universal service funds to subsidize broadband services, are not necessarily invalid after Comcast. That is because section 254 of the Act likely allows the FCC to both collect USF contributions from and — as reflected in the E-rate program — use them for “advanced services” like Internet access. Nor does the Comcast decision by the D.C. Circuit necessarily spell the death knell for the Commission’s National Broadband Plan. Some of its proposals, such as privacy protections for broadband end users and truth-in-billing disclosure requirements for ISPs, would surely require new legislative authority. Yet the basic objectives of the plan, including its proposal to allocate an additional $16 billion in universal service funds to subsidize broadband services, are not necessarily invalid after Comcast. That is because section 254 of the Act likely allows the FCC to both collect USF contributions from and — as reflected in the E-rate program — use them for “advanced services” like Internet access.

The final FCC option is to reconsider its earlier rulings that Internet access services (at least when integrated with IP transport) are “information services” for purposes of the 1996 Act’s classifications. Some analytical jujitsu would obviously be required to achieve that result, since the agency needs to develop and articulate changed circumstances that rationally justify a reversal of its prior ruling. But since the Supreme Court has recently emphasized that the APA does not impose on administrative agencies any higher burden of justification to repeal or revise its rules and policies than to adopt them in the first place, the FCC conceivably might be able to satisfy that standard.

Much of the opposition to this sort of “reclassification” stems from the fear that characterizing Internet access as a telecommunications service would carry with it the full panoply of legacy Title II dominant carrier regulation, such as rate-of-return pricing, entry and exit licensing and the like. The two, however, are not co-extensive. It has been the law for several decades, codified by Congress in 1996, that the FCC enjoys the ability to refrain or “forbear” from regulation. Reclassifying broadband as a Title II telecom service could, at least hypothetically, be coupled with a simultaneous decision forbearing from application of most substantive regulations to ISPs.4/ Yet at least to public interest advocates, that would be viewed as a loss; in their regulatory paradigm broadband represents the new common carriage and should be offered on a quasi-utility basis. That perception will need to be changed if proponents of reclassification are to stand a realistic chance of persuading the agency and, more importantly, successfully withstanding judicial review.

Finally, under both the Bush and Obama Administrations the FTC has expressed a clear desire to exercise its own statutory jurisdiction over broadband services. Historically, the FTC is precluded from applying the Federal Trade Commission Act and its unfair competition and consumer protection standards to common carriers. But absent reclassification, broadband is plainly not a common carrier service under either the Communications Act or the FTC Act. As a result, although FTC Chairman John Liebowitz has not made a public statement to date in the wake of Comcast, most observers expect that agency to move relatively rapidly into broadband for purposes of filling the void left in the wake of the court of appeals’ decision.

Conclusion

Network neutrality is a complex, contentious and confusing issue. While the D.C. Circuit’s opinion is abundantly clear, it is not apparent how the FCC or Congress will respond and whether the agency will seek Supreme Court certiorari review to test the basis and scope of its ancillary jurisdiction. Having persisted formally since 2005, and as a matter of policy debate for more than a decade, net neutrality is not necessarily dead, it is just entering a new phase of consciousness. That it looks comatose is perhaps a mirage that will be evaporated with time.

Footnotes

1/ Court Limits FCC Power Over Internet,” Boston Globe, April 7, 2010; Editorial, “FCC Must Quickly Reclaim Authority Over Broadband,” San Jose Mercury News, April 7, 2010; “FCC to Start Writing Internet Rules After U.S. Court Setback,” Business Week, April 8, 2010.

2/ Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), chair of the House Committee on Energy & Commerce, announced almost immediately that he is “working with the Commission, industry, and public interest groups to ensure that the Commission has appropriate legal authority to protect consumers.” Waxman Statement, April 6, 2010. Earlier, in July 2009, Reps. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) and Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.) introduced H.R. 3458, the Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2009, to enshrine what the legislation terms “Internet freedom” into law. However, In 2006 Congress failed to pass five bills, backed by groups including Google, Amazon.com, Free Press and Public Knowledge, that would have handed the FCC the power to oversee network neutrality compliance.

3/ See also R. McDowell, “Hands Off the Internet,” Washington Post, April 8, 2010.

4/ In response to concerns voiced regarding reclassification, Rep. Markey said that even under Title II, the FCC could forbear if it wanted to” and that in the past it had “availed itself” of that power. “We shouldn’t pretend that going back to Title II would mean that the earth would stop spinning on its axis and it would be the end of times,” he added. See “Concerns About Title II Reclassification Aired at House Hearing on Broadband Plan,” T.R. Daily, April 8, 2010.

|

|

Yet a third set of issues has received scant attention in the business media. That is, how would an Apple STB deal with the 1996 legal mandate that so-called “navigation devices” be available for retail purchase by consumers, in other words unbundled from cable television and broadband service? Apple is known to have the most popular, addictive and tightly integrated ecosystem of all technology companies. The company is famous for steadfastly protecting this closed ecosystem and declining to make its hardware, or most software, interoperable with other platforms. The devices and software Apple sells are designed to work well with each other and sync easily so that preferences and media can be copied or shared with multiple devices without much effort. Applications work on many devices at the same time — even with a single purchase — and user interfaces are very similar across devices. Sure, out of necessity Apple offers iTunes software for Windows (supporting both the iTunes Store for music and video purchases and iPhone syncing on Windows PCs), but at their core most Apple products work best, if at all, only with other Apple products.

Yet a third set of issues has received scant attention in the business media. That is, how would an Apple STB deal with the 1996 legal mandate that so-called “navigation devices” be available for retail purchase by consumers, in other words unbundled from cable television and broadband service? Apple is known to have the most popular, addictive and tightly integrated ecosystem of all technology companies. The company is famous for steadfastly protecting this closed ecosystem and declining to make its hardware, or most software, interoperable with other platforms. The devices and software Apple sells are designed to work well with each other and sync easily so that preferences and media can be copied or shared with multiple devices without much effort. Applications work on many devices at the same time — even with a single purchase — and user interfaces are very similar across devices. Sure, out of necessity Apple offers iTunes software for Windows (supporting both the iTunes Store for music and video purchases and iPhone syncing on Windows PCs), but at their core most Apple products work best, if at all, only with other Apple products.