A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

Disintermediation is the heart of the Internet’s value proposition; cutting out the middleman in order to reduce distribution costs at scale. Now the first and best example of this point, Amazon.com, is quietly going a bit in the other direction.

According to a report Monday by Reuters, Amazon is installing “lockers” in 1,800 Staples office supply stores nationwide. These are not cloud-based digital content lockers, but instead large automated dispensing machines.

The Amazon lockers at Staples will allow online shoppers to have packages sent to the office supply chain’s stores. Amazon already has such storage units at grocery, convenience and drug stores, many of which stay open around the clock. Amazon.com Inc., the world’s largest Internet retailer, is trying to let customers avoid having to wait for ordered packages due to a missed delivery.

The reason for Amazon’s move, which Seattle-based GeekWire says was quietly launched a year ago, is not difficult to figure out. The “last 30 yards” are the most important part of its supply chain, for which Amazon largely relies on UPS. Yet as consumers, especially Americans, now spend little or no time at home during business hours, there is often no one available at the shipping address to receive packages. That makes the opportunity cost of buying from Amazon, namely the time required for delivery, higher than otherwise the case, in turn making alternatives such as Walmart, Apple and Best Buy in-store pick-up or RedBox DVD rental kiosks far more attractive to buyers. Marketing experts call this the “omnichannel” retail strategy, designed to prevent “showrooming.”

The irony is clear. A company born on the Web, one that essentially birthed the distinction between virtual and brick-and-mortar retailing, is making a big investment (including whatever undisclosed fees it will pay to Staples) in the very companies its business model threatens. While Apple’s retail stores may have been unexpected for a PC manufacturer, they represented an incremental change to the company’s distribution system. Amazon, in contrast, is moving stealthily into a new, mixed-mode business model that embraces part of the IRL retailing segment it once promised to make irrelevant.

Whether this will make a competitive difference remains to be seen. Consumers can now (literally) vote with their feet.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

So much media attention was paid to the spectacular collapse of U.S. Senate deliberations on a cybersecurity bill in August — and the Obama Administration’s controversial move to fashion an Executive Order on the subject — that few if anyone focused on the biggest change affecting the data protection landscape. The Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) guidelines on disclosure of cyber attacks by publicly traded corporations have become de facto rules for at least six companies, including Google Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., according to recent agency enforcement letters.

Last fall, the SEC completed a long process of issuing staff “guidance” on when cybersecurity risks must be disclosed in public company securities filings (annual reports, 10Qs, etc.). The sensible conclusion was that if a hack or intrusion would be “material” to an ordinary investor, corporations need to disclose the cyber risk and discuss their actions to ameliorate or prevent it. Unlike Y2K, however, these guidelines, released by the SEC’s corporate finance section, did not come with a “safe harbor” for disclosing companies. In 1999, congressional legislation created a legal safety zone for Y2K disclosures, avoiding liability under the Securities Act of 1934, that has not been replicated with respect to more general cybersecurity risks. Last fall, the SEC completed a long process of issuing staff “guidance” on when cybersecurity risks must be disclosed in public company securities filings (annual reports, 10Qs, etc.). The sensible conclusion was that if a hack or intrusion would be “material” to an ordinary investor, corporations need to disclose the cyber risk and discuss their actions to ameliorate or prevent it. Unlike Y2K, however, these guidelines, released by the SEC’s corporate finance section, did not come with a “safe harbor” for disclosing companies. In 1999, congressional legislation created a legal safety zone for Y2K disclosures, avoiding liability under the Securities Act of 1934, that has not been replicated with respect to more general cybersecurity risks.

The recent SEC enforcement steps also have taken place at the corporate finance division level, but presumably with the informal approval at least of SEC Chair Mary Schapiro. In these cases, the agency “requested” that a number of large Internet companies clarify or modify their SEC filings to disclose cyber incidents that previously had not been reported to investors. In April, the SEC asked Amazon to disclose in its next quarterly filing that hackers had raided its Zappos.com unit, stealing addresses and some credit card digits from 24 million customers in January, which Amazon did. Google likewise agreed in May to put a previously disclosed cyber atack in its formal earnings report. AIG, Hartford Financial Services Group, Eastman Chemical and Quest Diagnostics were also asked to improve disclosures of cyber risks, according to agency staff correspondence reported by Bloomberg News.

As one example, here is the relevant excerpt from the corporate finance staff’s May 2, 2012 letter to Google CEO Larry Page:

We note your disclosure that if your security measures are breached, or if your services are subject to attacks that degrade or deny the ability of users to access your products and services, your products and services may be perceived as not being secure, users and customers may curtail or stop using your products and services, and you may incur significant legal and financial exposure. We also note your Current Report on Form 8-K filed January 13, 2010 disclosing that you were the subject of a cyber attack. In order to provide the proper context for your risk factor disclosures, please revise your disclosure in your next quarterly report on Form 10-Q to state that in the past you have experienced attacks. Please refer to the Division of Corporation Finance’s Disclosure Guidance Topic No. 2 at http://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/guidance/cfguidance-topic2.htm for additional information.

The difference between fall 2011 and spring 2012 is that, irrespective of the formal legal effect of staff guidance, the SEC is using its administrative processes to produce a disclosure result not specifically compelled by the agency’s rules for corporate securities filings. That in itself is not surprising, since the securities laws and implementing SEC regulations are broad enough to encompass any factor, whether financial or otherwise, that could affect stock prices. Here, the SEC staff opined in its guidance that basic SEC rules about market manipulation, insider trading and misleading shareholders (e.g., Rule 10b-5) required disclosure of cyber incidents and cybersecurity risks by any business potentially affected by hacking. And that’s obviously not confined to online retailers or Web-centric businesses.

The bigger question is how businesses can protect themselves from the embarrassment of such compelled, government-mandated cyber disclosures and the even greater potential for fines and formal enforcement actions the SEC may utilize in the IT security realm going forward. Here are a few pointers:

- Do not assume that merely because your business is not online, cybersecurity cannot affect the company. Hundreds of “brick and mortar” retailers, for instance, have had consumer credit card records breached.

- Treat data security just like your securities lawyers treat any other risk to the business’s future, since that is how federal regulators view cyber risks.

- Do not assume the SEC’s focus on cybersecurity is limited to public companies, because the underlying rules cited by its corporate finance division apply just as much to private placements as they do to proxy solicitations and 10K reports.

- When disclosing IT security risks, make sure they are balanced by something concrete and proactive to prevent, or diminish the severity of, cyber attacks. Otherwise diclosures may have the opposite effect of encouraging shareholder class action litigation.

- Work closely with compliance counsel, IT technology experts and your insurance carriers to develop workable cybersecurity assessment and intrusion notification regimes, internally and externally. This should not only reduce legal exposure, but going forward lower the company’s costs for cyber insurance. Periodic outside reviews should provide both comfort and legal protection to CEOs or CFOs signing SEC submissions.

These SEC staff actions were balanced by the traditional caveat that “our comments or changes to disclosure in response to our comments do not foreclose the Commission from taking any action with respect to the company or the filings and the company may not assert staff comments as a defense in any proceeding initiated by the Commission or any person under the federal securities laws of the United States.” But the chances the full SEC would prosecute a public company for following staff suggestions are remote. On the other hand, for public corporations that ignore this lesson, and fail to disclose cybersecurity risks, we suspect only pain and expense — most likely in a Commission prosecution or fine — lie in their SEC futures. So rules are really rules, even when they are not.

Note: Originally written for and reposted with permission of my law firm’s Information Intersection blog.

According to the New York Times, Texas attorney general Greg Abbott has launched an antitrust investigation of Google, based on the concept that deviations from “search neutrality” are anticompetitive and unlawful. Texas Attorney General Investigates Google Search | NYTimes.com.

The examination involves the fairness of Google search results, a concept called search neutrality. Some companies worry Google has the power to discriminate against them by lowering their links in search results or charging higher fees for their paid search ads.

This is utterly ridiculous. Google does not compete with the companies listed in its search results, but instead with other search engines for advertising. Anything Google may or may not do — and its mathematical algorithms leave precious little room for human bias — in Web search query results has no effect whatever on advertising competition. Search is by definition subjective because someone or something has to rank and order sites, but more importantly it is a free product. If anything, search bias would harm Google and help its search competitors (principally Microsoft-Yahoo!) by giving them a competitive advantage for search users looking for so-called “objective” Internet search results.

And in the only relevant market that counts — advertising — search neutrality is completely irrelevant. Even if advertisers pay for higher listings in search placement, as they can do for all Internet and search advertising (including “sponsored” or “promoted” search results on every major search site), that’s no different from paying for a full-page or inside front cover ad in a traditional magazine or newspaper. In the marketplace, that’s a completely acceptable, in fact desired, method of competition.

Now the search neutrality complainants argue that Google can “leverage” its search dominance into other markets. For instance, they say:

with its so-called Universal Search setup, Google is using its search engine monopoly — which controls an estimated 85 per cent of the global market — to unfairly favor its own services over those of its competitors. Universal Search transforms Google’s ostensibly neutral search engine into an immensely powerful marketing channel for Google’s other services. [I]t allows Google to leverage its search engine monopoly into virtually any field it chooses. Wherever it does so, competitors will be harmed, new entrants will be discouraged, and innovation will inevitably be suppressed.

Why the [EU] Google Antitrust Complaint is Not About Microsoft | The Register

As any antitrust lawyer knows full well, “leveraging” as a competitive concern is not unlawful and represents a discarded, 1960s-era theory of antitrust law. So this Texas investigation is really social policy (and bad policy, at that) on search engine technology masquerading as an antitrust issue. Get with it, A.G. Abbott, and be honest about what you are doing, which has nothing at all to do with competition or antitrust.

Even worse, if the Times’ sources are right, it seems that Microsoft itself, and my old antitrust colleague Rick Rule of Cadwalader, are behind the investigation.

The Texas attorney general has asked Google for more information on several companies, Google said. They include Foundem, a British shopping comparison site, SourceTool, a business search directory and myTriggers, which collects shopping links. In [a] Google blog post, [a company rep] drew an association to Microsoft. He said that Microsoft finances Foundem’s backer and that its antitrust attorneys represent the other two. Foundem is a member of the Initiative for a Competitive Online Marketplace, a European group co-founded and sponsored by Microsoft. SourceTool and myTriggers are clients of Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft, the law firm that represents Microsoft on antitrust issues.

Note also that Foundem runs the searchneutrality.org Web site.

I don’t agree with guilt-by-association for lawyers in private practice. But if Microsoft is financing these complaints, that just reinforces my long-held view that antitrust laws can be and frequently are used strategically to restrain competition and block rivals just as much as they can and should be used to pry open markets from dominance by monopolists.

You pick which motivation is at work here. My conclusion is obvious.

My Troutman Sanders colleagues have written before on the continuing judicial wrangling over whether GPS tracking devices, as well as location data maintained by wireless telecom providers, require a warrant before search and seizure by the government. Last July, a New York state court ruled that a government employer did not need a warrant to attach a GPS device to an employee’s car and monitor his movements continuously for a month, contradicting an earlier decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court. More recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held — after a thorough review of precedent dating all the way back to 1981 — that law enforcement agents must indeed first obtain a warrant based on probable cause to attach a GPS device to a criminal suspect’s vehicle.

Cases dealing with this issue merit watching because they represent the “front lines” of the intersection between personal privacy and technological capability. The Supreme Court in United States v. Jones, 131 S. Ct. 3064 (2011), decided that GPS tracking generally requires a warrant,  but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider. but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider.

So what does all this mean for the business community? Although law enforcement and the rather esoteric realm of constitutional law has been at the front lines of GPS privacy, there are a number of developments indicating that location privacy is also an important business issue:

First, the Federal Trade Commission — which functions as the de facto privacy regulator in the United States — has launched an inquiry into GPS tracking with a seminar convened on February 19 in Washington, D.C. This followed an FTC staff report last year, titled Mobile Privacy Disclosures: Building Trust Through Transparency, which “recommended” that companies consider offering a Do Not Track (DNT) mechanism for smartphone users among other measures to protect location privacy. Since the FTC has authority over unfair trade practices, including privacy, in almost every industry other than telecommunications, this initiative portends a risk of administrative sanction for private businesses not offering consumer choice as part of location-based services.

Second, HTC and Samsung smartphones come pre-loaded with software from the company Carrier IQ. More than 100 lawsuits filed since 2011 in federal court claim the phones unlawfully track the keystrokes of text messages and Internet searches. While the company maintains that the data are collected for customer support and to help troubleshoot network problems, it has become embroiled in litigation despite serving only as a technology vendor to other, far larger firms. (Not to leave them out, both Microsoft and Apple have also been sued over the location tracking features of their phones.) The lesson of Carrier IQ is that businesses are at risk in the GPS space even where they are not consumer-facing enterprises.

Third, a number of start-ups (Turnstyle, RetailNext, Nomi, shopkick, etc.) offer brick-and-mortar retailers the ability to use indoor location sensors and security video feeds to track movements of shoppers, recreating in the retail realm the same in-depth data on customer behavior that online merchants have long collected. Some of these firms follow best-practices by obtaining explicit opt-in for location information sharing. But the potential for adverse consumer reaction, and class action litigation, remains high ever since Nordstroms was caught in a PR whirlwind in July and unilaterally discontinued its in-store location program after notifying shoppers they were being tracked.

Fourth, it matters not whether a company is actually in the business of commercializing GPS data. In December, the FTC settled with the makers of an Android flashlight app after the agency claimed the company’s privacy policy was deceiving users into sharing their location and personal information with third-party advertisers. So there is still legal exposure for location information collection even if a firm operates in a completely different space.

Legal maneuvering can, at least for now, offset some of these risks. Under the current rules governing consumer class actions, several courts have decreed that privacy injury is insufficiently direct and substantial economically to support standing or to qualify for class action certification in federal court. For instance, in a case challenging a mobile app’s collection of geo-location data without consent, Goodman v. HTC America, Inc., the Western District of Washington held that the putative class members had not sufficiently plead injury to have standing. The court accepted as cognizable injuries overpayment for phones (because the plaintiffs would have paid less if they knew their location was to be collected as alleged) and diminution in value of the phones because of reduced battery life caused by the collection of geo-location data. Still, the court concluded that the “assertion that defendants misappropriated their personal information is not a sufficiently particularized injury to support [plaintiffs’] standing.” Yet since this opinion, and others from similar cases, holds out the possibility that identity theft or other financial harm may in the future result from insecure information collection, the standing defense appears to be time-limited.

The 4th Amendment protects people only from overreaching by the government. That may have led some in the business community to conclude prematurely that GPS and location tracking are issues only of concern to hackers and criminal enterprises. As these four developments show, however, location privacy is a serious business issue too.

Note: Originally written for and reposted with permission of my law firm’s Information Intersection blog.

When is a prediction not worth relying upon? For purposes of analyzing mergers under the Clayton Antitrust Act, a recent decision in favor of the Justice Department indicates that predictions are worth less — perhaps are even worthless — when they are contradicted by the actual facts of the marketplace. The government’s successful legal challenge a couple of weeks ago to the merger of two Internet start-ups ironically shows that the force of predictive judgments remains powerful, even when courts could employ reality as a basis for accurate comparison.

Some background. A 2013 DisCo post authored by the undersigned contrasted “future markets,” where the contours of products and entry do not yet exist and cannot reliably be predicted, with “nascent markets,” in which those features indeed exist but only in their infancy. My thesis was that antitrust enforcement in the latter is preferable because looking back at nascent markets once they have a chance to develop gives the government a more accurate basis on which to assess the actual impact of mergers and concentration than rank projections in which policymakers have no comparative expertise.

The case used to illustrate this theme was United States v. Bazaarvoice, Inc., in which the Justice Department sued to unwind a 2012 merger, already completed, between two firms in what it called the online ratings and reviews platform market. I concluded that

by challenging the merger post-consummation, DOJ has avoided basing its enforcement decisions on predictions of future markets and instead the case should rise or fall on the accuracy of its ex post analysis of actual competitive effects.

That’s not at all what happened, though.

Continue reading Is Bazaarvoice Bizarre?

Every new year sees a slew of top 5 and top 10 lists looking backwards. Here’s one that looks forward, predicting the five biggest disruptive technologies and threatened industries for 2014.

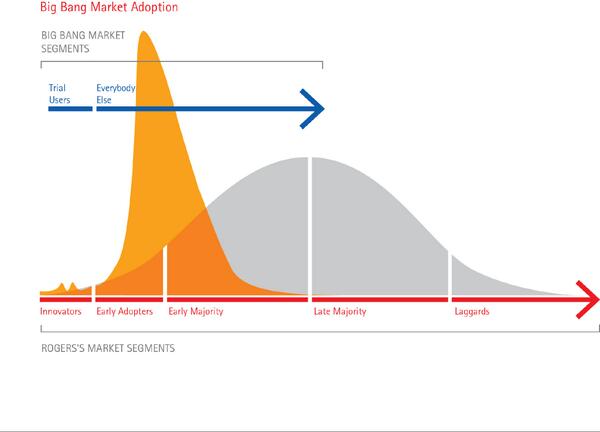

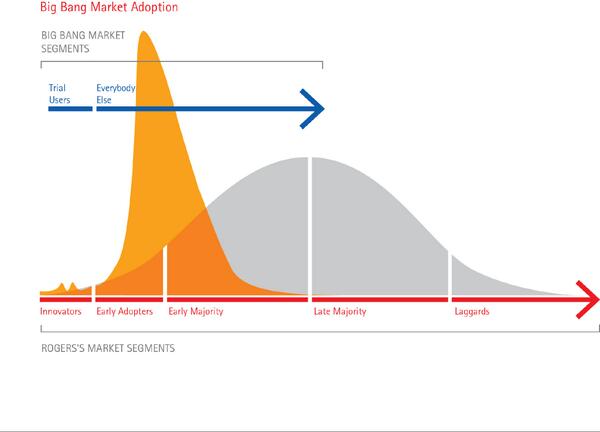

Making projections like these is really hard. Brilliant pundit Larry Downes titles his new book (co-authored with Paul Nunes) Big Bang Disruption: Strategy In an Age of Devastating Innovation. Its thesis is that with the advent of digital technology, entire product lines — indeed whole markets — can be rapidly obliterated as customers defect en masse and flock to a product that is better, cheaper, quicker, smaller, more personalized and convenient all at once.

Since adoption is increasingly all-at-once or never, saturation is reached much sooner in the life of a successful new product. So even those who launch these “Big Bang Disruptors” — new products and services that enter the market better and cheaper than established products seemingly overnight — need to prepare to scale down just as quickly as they scaled up, ready with their next disruptor (or to exit the market and take their assets to another industry).

Disruptors can come out of nowhere and happen so quickly and on such a large scale that it is hard to predict or defend against. “Sustainable advantage” is a concept alien to today’s technology markets. The reputation of the enterprise, aggregated customer bases, low-cost supply chains, access to capital and the like — all things that once gave an edge to incumbents — largely no longer exist or are equally available to far smaller upstarts. That’s extremely unsettling for business leaders because their function is no longer managing the present but inventing the future…all the time.

I certainly have no crystal ball. Yet just as makers of stand-alone vehicle GPS navigation devices were overwhelmed in 2013, suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere, by smartphone maps-app software, e.g., Google Maps, etc., so too do these iconic industries and services face a very real and immediate threat of big bang disruption this year.

Continue reading 5 Industries Facing Disruption In 2014

Despite the failures in recent years of such well-known retail chains as Circuit City, Borders and the like, it is way too soon to declare that the Internet will replace brick-and-mortar retailing. In part that is because consumer research suggests that in some segments, such as clothing, feeling and touching merchandise is an important part of the buying experience. Of interest to students of technological disruption, retailers are beginning in earnest to deploy technologies marrying the best aspects of online retailing with shopping malls and physical stores.

Delivery is one area where online retailers remain at a disadvantage. Amazon counters with its Prime membership for free two-day delivery, Amazon Lockers for local pick-up and its experimental foray into drone deliveries. Startups like Deliv (described as “a crowdsourced same-day delivery service for large national multichannel retailers”) are now providing equivalently fast store or home delivery for both online and in-person purchases.

Four of the nation’s largest mall operators are turning their properties into mini-distribution centers for rapid delivery, meaning shoppers can ditch their bags and keep spending. The service promises set delivery times for purchases consumers make at the mall or online from mall tenants, facilitated by a Silicon Valley start-up, Deliv Inc….The move highlights how delivery has become a key battleground in the war between physical and online retailers.

Startup Offers Same-Day Delivery at Shopping Malls | WSJ.com.

That in itself is remarkable. It shows that disruption is not a one-way street for legacy retailers. Yes, theirs is a challenging business environment, but technology is beginning to supply features for physical stores that meet and in some cases can beat online shopping providers. Home Depot, for instance, offers a smartphone app that allows consumers to check store inventory and aisle location, scan QR and UPC codes to get more information about products and order online with in-store delivery, overcoming some of the chain’s long-standing weaknesses: confusing layouts, out-of-stock merchandise and resulting abandoned visits.

Perhaps the most controversial realm is that of in-store consumer tracking and special offer distribution. This made news just last week when Apple Inc. turned on its iOS7 “iBeacon” service at its own retail stores. Macy’s has activated a shopkick-powered service through which simply walking into a Macy’s location will automatically send specialized offers to customers depending on where they are in the store. As Wired observed:

That’s just the beginning, though. Retailers are already talking about things like in-store navigation and dynamic pricing, all made possible by beacon-enhanced retail locations. For independent shops, iBeacon is a chance to jump into the smartphone era with one fell swoop. A $100 beacon is all it takes for even the mustiest book store to track customers, make recommendations, and offer discounts to customers’ pockets.

The risk, however, is that consumers may reject secret tracking technologies that retailers use internally, absent notice and consent. Over the last two years, retailers such as Nordstrom have hired software firms that gather Wi-Fi and Bluetooth signals emitted from smartphones to monitor shoppers’ movements around stores. They use the data to study things like wait times at the check-out line and how many people who browse actually make a purchase. At the prompting of Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) and the Washington, DC-based advocacy group Future of Privacy Forum, several location-tracking firms agreed in October to a code of conduct under which they will ask retailers to post signs in “conspicuous” spots in stores which inform consumers that their movements are being monitored and direct them to a website where they can opt-out. As Kashmir Hill noted in Forbes:

As with many novel and unexpected uses of technology, people have tended to be creeped out by the practice when they learn about it. Ask Path, which was tracking shoppers in malls (in 2011). Or Nordstrom, which came under fire earlier this year for tracking its shoppers without clear notice. Or London, which was using trash bins to collect info from passerbys’ mobile devices.

The flip side is that by offering recommendations and deals with an opt-in policy, retailers could dramatically bridge the divide between the online and brick-and-mortar experiences, making the latter still more like the former. Few consumers react negatively to Amazon or Netflix offering recommended products based on their past purchases. By doing the same thing in real-time, when a shopper passes the relevant store aisle or section, physical retailers would be in a position to offer something no e-commerce site can match: customized shopping with the ability to see, feel and take home impulse purchases enabled by technology.

There remain a slew of legal questions about whether the data collected by location-technology providers and retailers qualifies as personally identifiable data subject to the European Union Privacy Directive and the corresponding EU Safe Harbor in the U.S. In this country, it seems likely that the unique phone IDs associated with wireless devices — which are only linked to subscribers in the carrier’s switching and billing systems — would not be considered personal data by the Federal Trade Commission. In Europe, countries like the Netherlands and France have already articulated a more expansive view which could encompass device information in addition to name, address, phone numbers and the like. But even in the more liberal America, some have questioned whether retailers will be forced, whether by consumers or regulators, to dial-back autonomous tracking and adopt more transparent location practices.

All of this brings back memories for me personally. Nearly 15 years ago, I represented a start-up that was developing GPS chips for smartphones. While they are now ubiquitous (the start-up was sold to Qualcomm in March 2000), the challenges in making GPS work without a dedicated, external antenna were substantial. So like any good disruptor, my client went to the Federal Communications Commission to advocate cell phone location rules for E911 service that could give it a competitive advantage in the marketplace. The anecdote we used in our lobbying was that McDonald’s could message your phone, when passing one of its outlets, asking “Have you had your break today?” (That certainly dates the message, of course).

Technology has evolved so much that shopping is now almost at that place. Location tracking platform providers and their retail clients are offering a degree of interactivity never before available at retail. Whether it is compelling or creepy to consumers, of course, remains to be determined.

Note: The author has represented shopkick Inc., but not in connection with the company’s privacy policies and practices. Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

As a recent story from the The Washington Post illustrates well, “tradition” is a gating factor in the ongoing transformation of the legal industry. Despite the highly conservative nature of courts, bar associations and attorneys, however, in the post-Great Recession legal market of 2013, technology and changing values are rapidly disrupting traditional legal services.

My colleague and friend Jonathan Askin, Founder of the Brooklyn Law Incubator & Policy Clinic, hosted a seminar on legal start-ups in late August. Many of the companies highlighted there are focused on low-hanging fruit, taking the trend started by LegalZoom of moving do-it-yourself work product to consumers into spaces that for decades have remained buttoned-up by prohibitions against “unauthorized practice of law” and the resistance of lawyers to allowing clients document control. (LegalZoom itself has been challenged by bar groups and class action plaintiffs in North Carolina, Connecticut, Missouri and California for allegedly engaging in the practice of law, a classic and anticompetitive use of regulations designed to protect consumers, not prohibit new business models.) Like taxi-hailing companies Uber and Sidecar, legal start-ups thus face opposition from incumbents who are well-situated to employ archaic regulatory regimes to thwart new entry.

Nonetheless, the four emerging firms Askin profiled make a persuasive case that the guild-like barriers which for centuries protected lawyers from competition are breaking down before our eyes.

- Shake allows consumers to create binding contracts automatically on their smartphones or tablets with a few Q&As and then sign them electronically.

- Lawdingo leverages the power of networking to connect consumers to lawyers for real-time quick (and often free) answers on a virtually unlimited number of topics.

- Caserails offers cloud-based document assembly and editing functionalities for individuals or groups, long the bane of corporate transactions.

- Priori Legal allows SMBs to select among a trusted community of lawyers for discounted or fixed-rate engagements with Web-based comparison shopping.

The best and brightest of these firms will undoubtedly rise to the top over time. Much like banks in the 1970s — when toasters as deposit “gifts” were replaced by deregulated interest rates and tellers by ATMs — legal consumers no longer care or very much appreciate the old traditions of the legal profession, especially its convoluted language, fancy office space and expensive artwork. The successful start-ups in this steady disintermediation of legal services will be the ones who recognize that they are driven by what legal transactions can and will be, not what they have been historically, and that they are technology companies solving legal problems, not legal companies trying to understand technology. Continue reading Disrupting the Legal Industry

Are copyright holders allowed to decide without legal constraint to whom they will license their content and on what terms? That is the issue facing Pandora and other new streaming radio firms, for whom music and its associated licensing fees represent the biggest hurdle to commercial success against more established broadcast radio competitors. The answer lies in the sometimes obscure interface between the Copyright Act and antitrust law in the U.S.

In Pandora Media, Inc. v. American Society of Composers, Authors & Publishers, an antitrust case currently pending in federal court in New York, the streaming company is suing ASCAP and some of the major record labels for “withdrawing” their content from the ASCAP joint licensing venture, thus forcing individualized negotiations. It’s a leading-edge dispute, scheduled for trial by year-end, that may help catalyze a new approach to the old question of whether — and if so to what extent — owners of copyrighted digital content are permitted to refuse to deal with competing distribution channels on dramatically different commercial terms.

Most Project DisCo readers likely know about Pandora, a prominent start-up in the Internet radio space — one of the hottest markets around these days, especially given the launch of iTunes Radio by Apple. What is less understood is that streaming music on the ‘Net is fraught with legal issues surrounding copyright, constraints that effectively function as a barrier to the more widespread adoption of such disruptive technologies.

That’s not a lot different from the case of streaming Internet television pioneer Aereo, which as Ali Sternburg points out is caught in legal limbo between different rules (from conflicting judicial decisions) in different regions of the county: and a whopping legal defense bill as well. Copyright in addition plays a key role in the current exemption of traditional over-the-air radio stations from licensing music, an implicit subsidy the recording industry has been lobbying to change for years.

The Pandora-ASCAP fight represents a tricky issue at the intersection of intellectual property (IP) and antitrust. The ASCAP litigation actually dates to 1941, when the government entered into a consent decree settling a complaint that alleged monopolization of performance rights licenses. The settlement, still in place more than 60 years later, requires the organization to license “all of the works in the ASCAP repertory.” A month ago, presiding District Judge Denise Cote (who also issued the decision finding Apple’s e-book pricing deals a violation of the antitrust laws) entered summary judgment for Pandora. She reasoned that the consent decree gave Pandora the legal right to a blanket license

even though certain music publishers beginning in January 2013 have purported to withdraw from ASCAP the right to license their compositions to “New Media” services such as Pandora. Because the language of the consent decree unambiguously requires ASCAP to provide Pandora with a license to perform all of the works in its repertory, and because ASCAP retains the works of “withdrawing” publishers in its repertory even if it purports to lack the right to license them to a subclass of New Media entities, [Pandora must prevail].

Continue reading Opening Pandora’s Box: Copyright and Antitrust

When it comes to disruption, the advent of social media communications is decidedly in the front row. But along with revolutionizing personal (and political) relationships, the sharing of content on social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr and Instagram — now a Facebook property — is steadily increasing pressures on a quite different regime, namely copyright law. The passage and forthcoming implementation in the UK of what has become known colloquially as The Instagram Act, boringly titled the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act, promises only to accelerate the conflict between new social media services and legacy copyright rules worldwide.

This author has written, and ranted, about ownership of user-generated content (UGC) for several years. The gist of the problem is not that social media providers want to claim ownership of UGC. None do, despite occasional outcries to the contrary, although they also insist rather unremarkably via terms of service (TOS) on a license to display UGC posts to those a user authorizes. Instead, the problem arises when third parties want to incorporate user-created content into their own sites or publications. After all, if CNN or Fox News broadcast tweets, status updates and Flickr photos as part of their news stories, wouldn’t these and other organizations be violating the inherent copyright users hold in their own content? Put another way, if posting users have legal rights to their UGC, doesn’t it follow that even “retweeting” constitutes unlawful copyright infringement?

In most of the world today, ownership of one’s creation is automatic, and considered to be an individual’s legally protected intellectual property. That’s enshrined in the Berne Convention and other international treaties, which abolished registration as a formal predicate for copyright interests (although not for judicial enforcement). What this means in practice is that one can go after somebody who exploits a creative work without the owner’s permission — even if pursuing them is cumbersome and expensive — once the work is registered with the appropriate governmental copyright authority.

Social media sharing throws all these regimes into chaos. Take first the issue addressed by The Instagram Act and, in a slightly different context, U.S. litigation over the Google Library service: “orphaned” works. The new UK law theoretically aims to make it easier for companies to publish orphan works, which are images and other content whose author or copyright holder can’t be identified. But whereas in the past, orphan works were often out-of-print books and historical unattributed photos, today millions of images are quickly orphaned online, as they move from Instagram to Twitter to Facebook to Tumblr without attribution along the way. The British response was to adjust copyright law so that an orphaned work can be republished without liability if a third party makes a “reasonably diligent” search to identify and locate the original owner.

Continue reading Social Media and Copyright Law In Conflict

|

|