A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

My Troutman Sanders colleagues have written before on the continuing judicial wrangling over whether GPS tracking devices, as well as location data maintained by wireless telecom providers, require a warrant before search and seizure by the government. Last July, a New York state court ruled that a government employer did not need a warrant to attach a GPS device to an employee’s car and monitor his movements continuously for a month, contradicting an earlier decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court. More recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held — after a thorough review of precedent dating all the way back to 1981 — that law enforcement agents must indeed first obtain a warrant based on probable cause to attach a GPS device to a criminal suspect’s vehicle.

Cases dealing with this issue merit watching because they represent the “front lines” of the intersection between personal privacy and technological capability. The Supreme Court in United States v. Jones, 131 S. Ct. 3064 (2011), decided that GPS tracking generally requires a warrant,  but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider. but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider.

So what does all this mean for the business community? Although law enforcement and the rather esoteric realm of constitutional law has been at the front lines of GPS privacy, there are a number of developments indicating that location privacy is also an important business issue:

First, the Federal Trade Commission — which functions as the de facto privacy regulator in the United States — has launched an inquiry into GPS tracking with a seminar convened on February 19 in Washington, D.C. This followed an FTC staff report last year, titled Mobile Privacy Disclosures: Building Trust Through Transparency, which “recommended” that companies consider offering a Do Not Track (DNT) mechanism for smartphone users among other measures to protect location privacy. Since the FTC has authority over unfair trade practices, including privacy, in almost every industry other than telecommunications, this initiative portends a risk of administrative sanction for private businesses not offering consumer choice as part of location-based services.

Second, HTC and Samsung smartphones come pre-loaded with software from the company Carrier IQ. More than 100 lawsuits filed since 2011 in federal court claim the phones unlawfully track the keystrokes of text messages and Internet searches. While the company maintains that the data are collected for customer support and to help troubleshoot network problems, it has become embroiled in litigation despite serving only as a technology vendor to other, far larger firms. (Not to leave them out, both Microsoft and Apple have also been sued over the location tracking features of their phones.) The lesson of Carrier IQ is that businesses are at risk in the GPS space even where they are not consumer-facing enterprises.

Third, a number of start-ups (Turnstyle, RetailNext, Nomi, shopkick, etc.) offer brick-and-mortar retailers the ability to use indoor location sensors and security video feeds to track movements of shoppers, recreating in the retail realm the same in-depth data on customer behavior that online merchants have long collected. Some of these firms follow best-practices by obtaining explicit opt-in for location information sharing. But the potential for adverse consumer reaction, and class action litigation, remains high ever since Nordstroms was caught in a PR whirlwind in July and unilaterally discontinued its in-store location program after notifying shoppers they were being tracked.

Fourth, it matters not whether a company is actually in the business of commercializing GPS data. In December, the FTC settled with the makers of an Android flashlight app after the agency claimed the company’s privacy policy was deceiving users into sharing their location and personal information with third-party advertisers. So there is still legal exposure for location information collection even if a firm operates in a completely different space.

Legal maneuvering can, at least for now, offset some of these risks. Under the current rules governing consumer class actions, several courts have decreed that privacy injury is insufficiently direct and substantial economically to support standing or to qualify for class action certification in federal court. For instance, in a case challenging a mobile app’s collection of geo-location data without consent, Goodman v. HTC America, Inc., the Western District of Washington held that the putative class members had not sufficiently plead injury to have standing. The court accepted as cognizable injuries overpayment for phones (because the plaintiffs would have paid less if they knew their location was to be collected as alleged) and diminution in value of the phones because of reduced battery life caused by the collection of geo-location data. Still, the court concluded that the “assertion that defendants misappropriated their personal information is not a sufficiently particularized injury to support [plaintiffs’] standing.” Yet since this opinion, and others from similar cases, holds out the possibility that identity theft or other financial harm may in the future result from insecure information collection, the standing defense appears to be time-limited.

The 4th Amendment protects people only from overreaching by the government. That may have led some in the business community to conclude prematurely that GPS and location tracking are issues only of concern to hackers and criminal enterprises. As these four developments show, however, location privacy is a serious business issue too.

Note: Originally written for and reposted with permission of my law firm’s Information Intersection blog.

A few weeks ago I examined how copyright law — like most legal subjects dealing with technology — is lagging behind the fast-moving and disruptive changes wrought by social media to old legal rules for determining rights to Internet content. Part of my critique was that in deciding ownership of user-generated content (UGC), courts have not yet evaluated the difference between posting content “in the clear” and restricting content to “friends” or some other defined class far smaller than the entire Internet community.

Things may at last be getting a bit more settled. A New Jersey federal court ruled last Tuesday that non-public Facebook wall posts are covered by the federal Stored Communications Act (18 U.S.C. §§ 2701-12). The SCA, part of the broader Electronic Communications Privacy Act (18 U.S.C. §§ 2510 et seq.) that addresses both “the privacy expectations of citizens and the legitimate needs of law enforcement,” protects confidentiality of the contents of “electronic communication services,” providing criminal penalties and a civil remedy for unauthorized access. It’s a decades-old 1986 law that was enacted well before the commercial Internet and either email or social media had become ubiquitous. Yet by interpreting the statute, in light of its purpose, to apply to new technologies, District Judge William J. Martini has done Internet users, and common sense, a great service.

Plaintiff Deborah Ehling, a registered nurse, paramedic and president of her local EMT union — apparently a thorn in the side of her hospital employer for pursuing EPA and labor complaints as well — posted a comment to her Facebook wall implying that the paramedics who arrived on the scene of a shooting at the D.C. Holocaust museum should have let the shooter die. Unbeknownst to Ehling, a co-worker with whom she was Facebook friends had been taking screenshots of her profile page and sending them to a manager at Ehling’s hospital.

Ehling was temporarily suspended with pay and received a memo stating that the hospital was concerned that her comment reflected a deliberate disregard for patient safety. After an unsuccessful NLRB complaint based on labor law, Ehling’s federal lawsuit alleged that the hospital had violated the SCA by improperly accessing her Facebook wall post about the museum shooting, contending that her Facebook wall posts were covered by the law because she selected privacy settings limiting access to her Facebook page to her Facebook friends.

Judge Martini concluded that the SCA indeed applies to Facebook wall posts when a user has limited his or her privacy settings. He noted that “Facebook has customizable privacy settings that allow users to restrict access to their Facebook content. Access can be limited to the user’s Facebook friends, to particular groups or individuals, or to just the user.” Therefore, because the plaintiff selected privacy settings that limited access to her Facebook wall content only to friends and “did not add any MONOC [hospital] managers as Facebook friends,” she met the criteria for SCA-covered private communications.

Facebook wall posts that are configured to be private are, by definition, not accessible to the general public. The touchstone of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act is that it protects private information. The language of the statute makes clear that the statute’s purpose is to protect information that the communicator took steps to keep private. See 18 U.S.C. § 2511(2)(g)(i) (there is no protection for information that is “configured [to be] readily accessible to the general public”). [The] SCA confirms that information is protectable as long as the communicator actively restricts the public from accessing the information.

That’s a bold move by a jurist sensitive to the constraints on Congress, especially one as polarized as we have in America today. It reflects a willingness to adapt the law to changing technology by application of the basic principles and purposes of legislation, even if the statutory framework is old and its language somewhat archaic. As Judge Martini observed with a bit of consternation, “Despite the rapid evolution of computer and networking technology since the SCA’s adoption, its language has remained surprisingly static.” Thus, the “task of adapting the Act’s language to modern technology has fallen largely upon the courts.”

Continue reading Friends With Benefits (How Privacy Law Evolves for Social Media)

If you’re read my The Law of Social Media essays or presentations, you probably know there have been few serious cases yet establishing law specifically targeting social media. One can apply basic principles to predict what courts will do, but so far there are only a handful of reported decisions that say anything at all about social media.

That does not mean nothing happened in 2010 in this rapidly evolving area. In my view, the most important developments are reflected in these four cases:

1. The Food & Drug Administration’s citation of Novartis for Facebook content that lacked required pharmaceutical side-effect warnings and disclaimers, and the agency’s subsequent delay in release of social media “guidance” for pharma until Q1 2011. The case illustrates that heavily regulated industries face special risks and burdens in structuring social media marketing campaigns.

2. The assertion of jurisdiction by the National Labor Relations Board over “protected activity” of employees (discussing working conditions, for instance) on Facebook, even where the company is not unionized. This shows that, although equal employment issues still dominate employers’ use of social media in hiring and firing, there may be limits to which companies can penalize workers for their social media posts if the content is work-related.

3. The New Jersey Supreme Court’s decision in in Stengart v. Loving Care Agency, Inc., reversing the older, black-letter rule that employees have no privacy interests at all in employer-provided email systems.

4. The decision just days ago by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit in United States v. Warshak, holding that the 20-year old Stored Communications Act’s approval of warrantless seizure by the government of user emails is unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment. This is the first judicial opinion that extends “reasonable expectations of privacy” from snail mail and the telephone to email, using a principled and thoughtful constitutional analysis.

Since the advent of email, the telephone call and the letter have waned in importance, and an explosion of Internet-based communication has taken place. People are now able to send sensitive and intimate information, instantaneously, to friends, family, and colleagues half a world away. Lovers exchange sweet nothings, and businessmen swap ambitious plans, all with the click of a mouse button. Commerce has also taken hold in email. Online purchases are often documented in email accounts, and email is frequently used to remind patients and clients of imminent appointments.

In short, “account” is an apt word for the conglomeration of stored messages that comprises an email account, as it provides an account of its owner’s life. By obtaining access to someone’s email, government agents gain the ability to peer deeply into his activities. . . . If we accept that an email is analogous to a letter or a phone call, it is manifest that agents of the government cannot compel a commercial ISP to turn over the contents of an email without triggering the Fourth Amendment.

And as my friends at SiliconANGLE have observed, the same rationale should apply as well to emails stored in “the cloud” or other Web-based email systems, like Gmail and Hotmail.

* * * * * *

So there you have ’em. Not quite as interesting as the worst-dressed actress and best cinema films lists we’ll see over the next few days, but (perhaps) a bit more relevant to our daily activities on social networks and the real-time Web.

Several of the previous posts in my The Law of Social Media essay series focus on core legal issues, such as copyright in user-generated content and employer use of social media for HR decisions. This one is a bit different. Like John Naisbitt, it describes what I am convinced are the most significant law/policy “megatrends” affecting the social media space today.

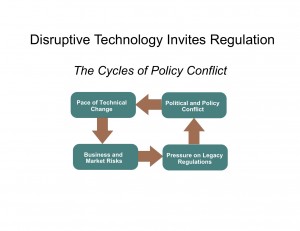

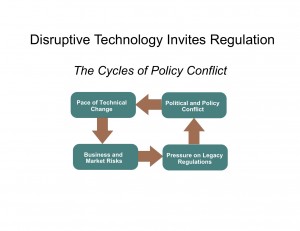

As an overview, consider the following scenario—and click for a larger image:

As the graphic indicates, the reality is that disruptive technologies quickly and visibly invite governmental regulation. That’s because change creates business and policy risks, which threaten legacy products and powerful business incumbents, and in turn which cause political pressures to protect established constituencies. Since social media is most assuredly a disruptive force, this circular pattern will likely manifest itself — in fact, as I discuss below it already has — in public policies towards social media and social networking communications.

1. Censorship & Filtering

Governments absolutely hate “unfiltered” social media and will move to censor and control it.

In the East, the basis for such censorship is political and religious oppression, as in Iran, North Korea, China, etc. In the West, the more unlikely culprit has been intellectual property (e.g., music and movie copyrights) and obscenity, as in Australia, France and New Zealand’s efforts to install country-wide porn filters and institute a “the strikes” rule against P2P file sharing. And everywhere, government mourns the loss of the historic financial and advertising basis for traditional media like newspapers and broadcast television, proposing to bail out or subsidize the latter in order to prevent social media from achieving dominance at the expense of last century’s communications technologies. Censorship is far from dead on the Web; in fact, it’s really only beginning.

2. Privacy

The EU’s strict data protection (privacy) regime will spread and overtake the US opt-out approach.

Most everyone knows that the European Union has a highly protective scheme of individual privacy in the digital age. Fewer understand that in the United States, with the exception of specially regulated industries like health care and financial services, the only privacy protections available are basically those the Constitution provides as against the government. That will change, however. The EU is too large a market for businesses to overlook, commerce today is fully globalized and while the United States remains the least privacy-centric of any major industrialized nation, that is changing as legislators and regulators more often choose an opt-in requirement for newer, albeit still infrequent, electronic privacy measures.

3. Criminal Law

Cyber offenses will (finally) be created.

In the past, criminal violations involving the Internet and online activities have largely focused on corporate interests, like the Anti-Cybersquatting, CFAA and CAN-SPAM Acts. But the current proliferation of pedophilia, cyber-bullling, stalking and other socially offensive digital-centric conduct is different. Many times, existing criminal laws — for instance, of assault — are not broad enough to cover online conduct. Other time, prosecutors are reluctant to indict and juries even more reluctant to convict. Yet the US congressional approach to indecency on the Web has for more than a decade been to attempt to ban conduct deemed seedy, whether pornography or gambling, to avoid having the “new” media infected with perceived old evils, for instance the Communications Decency Act of 1996. As a result, there is a good chance, well above 50% in my estimation, that the next several years will bring a proliferation of state and federal laws making criminally unlawful specific forms of online activity deemed socially deviant or harmful.

4. Anonymity

Anonymity on the Internet is under assault and may be lost.

A timely prediction, given that just yesterday two different courts compelled the unmasking of anonymous commenters in civil pretrial discovery—when the posters were not even parties to the cases. Ninth Circuit Upholds Unmasking of Online Anonymous Speakers and Illinois Appellate Court Unmasks Anonymous Commenters. There are a variety of reasons, but the principal one is that by defeating anonymity, politicians can be seen as “protecting” the victims of Web-based schemes, involving both antisocial (i.e., bullying, extortion, etc.) and anti-consumer (i.e., stock pump-and-dump chats, etc.) behavior, which sometimes end quite tragically, as in teenage suicides. This is reinforced by the continuing efforts of copyright holders (music, photos, video, news) to require ISPs to disgorge the identities of infringing users and by the FTC’s sponsored blogging “guidelines,” which support the theme of transparency from a consumer protection perspective. Almost alone among nations, only America has a Tom Paine and Federalist Papers/Primary Colors tradition of anonymous or pseudonymic political speech, yet even here — unless the Supreme Court intervenes — short-term passions, politics and national security phobias almost always trump free speech. The old proverb was that “No one knows if you are a dog on the Internet.” Don’t plan on barking much longer!

5. Competition

Competition and antitrust laws will reshape social media providers.

My core training is in antitrust law, although this megatrend has little to do with yours truly. Instead, it stems from the reality that Facebook, Apple and Google, among others, are already facing competition law investigations in the advertising, mobility, search and handset markets. From an economic perspective, there are very strong, positive network effects in social media, far greater than were true in the 1990s for Microsoft’s WIndows OS. As a consequence, viral expansion leads to small social media companies getting VERY big VERY fast: witness Facebook’s 500 million users and Twitter’s phenomenal hockey-stick growth curve. It is difficult for entrepreneurs to shake the old underdog mentality even when their companies become big enough that market power makes their business practices and acquisitions suspect, as Mark Zuckerberg is now learning to his chagrin. And when fueled by financial underwriting from legacy competitors — the dark political underbelly of Washington, DC and Brussels, Belgium antitrust battles — the “nascent” stucture of social media and wireless markets has, to date, not proven sufficient to keep the mitts of antitrusters from the US Department of Justice and the EU’s Competition Directorate from meddling—e.g., Google/Yahoo (2008-09) and Oracle/Sun (2009-10), to name a couple of examples.

6. Location

Location-bsed services will spawn a host of new policy battles.

“Location, location, locations” is not just a real estate slogan, it’s the cross-hairs for a number of policy trends affecting social media. The indicia are not found not just in the geometrically increasing popularity of geo-tagged photos, location check-in apps and games, and the like, but as well and perhaps more importantly in the fact that as wireless communications and data come to dominate telecom — a direct consequence of social networking — regulatory oversight follows almost automatically. “Nomadic” services like VoIP and video chart (e.g., FaceTime), in contrast, present an equally great threat to the established order by making location a matter of indifference. At bottom, this is an industry where eyeballs and advertising dollars still rule. So as marketers devise ever-clever ways to monetize users’ location (including the launch this week of my client shopkick’s location marketing app) all of the bad stuff that can happen online is bound, eventually, to arise with respect to location-based services. LBS isn’t bad; some people are bad. Unfortunately for the FourSquares and Gowallas of the social media world, that has never been enough in most societies to stop gun control—and it won’t be enough to arrest the coming push for consumer protection and marketing regulation in the location services space.

Note: I first used the “megatrends” metaphor while presenting at the 140 Characters Conference-DC (#140onf-dc) in June 2010, and am indebted to organizer Jeff Pulver for serving as my muse for these thoughts. Thanks, Jeff!

In my view, the second sentence here is the most important. If one posts material viewable by the entire world, the author implicitly licenses anyone to use the content-—in other words, no copyright applies, and the author does not “own” his or her user-generated content. The necessary corollary is that when the whole world can see your stuff, the government does not need permission, let alone a warrant, to look too.

Privacy law was largely created in the pre-Internet age, and new rules are needed to keep up with the ways people communicate today. Much of what occurs online, like blog posting, is intended to be an open declaration to the world, and law enforcement is within its rights to read and act on what is written. Other kinds of communication, particularly in a closed network, may come with an expectation of privacy. If government agents are joining social networks under false pretenses to spy without a court order, for example, that might be crossing a line.

Of course, where a social network allows users to restrict access, to friends or followers, the opposite conclusion holds. For instance, unless Facebook wall posts are made available to “everyone” in the user’s privacy settings, then there remain both legitimate ownership and privacy interests, such that the government can’t monitor that content without both probable cause and a warrant.

In response to what it terms its “customer’s needs,” Cisco will start to embed “lawful interception” capability into its router products. [C|Net News.com] What’s really going on here is that the convergence of packet-switched and circuit-switched networks is accelerating. So the law enforcement community is no longer content to give the Internet and ISPs a free ride when it comes to digital wiretapping, despite the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA). Cisco can’t be blamed, since it’s job is to sell products, but this is just another sign that the days of anonimity on the Internet are numbered.

|

|

but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider.

but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider.