A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

On behalf of the Sports Fans Coalition, I filed a brief yesterday with the FCC urging it to block the acquisition by Comcast Corp. of Time Warner Cable Inc. The gist of the argument is that the anticompetitive effects of vertical integration by cable systems have now reached crisis proportions with the ongoing refusal — already more than five months old and with no end in sight — of TWC to license Los Angeles Dodgers baseball games for cable or satellite distribution, or local broadcast, on any network other than its own SportsNet LA cable programming channel.

Hence this bold call for a remedy:

The Commission [should] hold the Applications in abeyance, declining to act all in this docket, unless and until TWC makes the SportsNet LA channel, and its exclusive Los Angeles Dodgers baseball content, available to all competing MVPDs at “fair market value and on non-discriminatory prices, terms and conditions,” and on the merits either (a) deny the Comcast-TWC request for transfer-of-control in its entirety, or (b) require the divestiture of all of Comcast’s RSN properties — sufficient for an independent competitor to operate the channels on profitable, going concern basis — as a condition to approving the acquisition of TWC.

Three high-level staffers at the Federal Trade Commission (Andy Gavil, Debbie Feinstein and Marty Gaynorare) are backing Tesla Motors Inc. in its ongoing fight to sell electric cars directly to consumers. As we’ve observed, Tesla forgoes traditional auto dealers in favor of its own retail showrooms. But that business model was recently banned by the New Jersey Motor Vehicle Commission — and is under fire in many other states as well — as a measure supposedly to protect consumers.

The ubiquitous state laws in question were originally put into place to prevent big automakers from establishing distribution monopolies that crowd out dealerships, which tend to be locally owned and family run. They were intended to promote market competition, in other words. But the FTC officials say they worry (as have we at DisCo) that the laws have instead become protectionist, walling off new innovation. “FTC staff have commented on similar efforts to bar new rivals and new business models in industries as varied as wine sales, taxis, and health care,” the officials write in their post. “How manufacturers choose to supply their products and services to consumers is just as much a function of competition as what they sell — and competition ultimately provides the best protections for consumers and the best chances for new businesses to develop and succeed. Our point has not been that new methods of sale are necessarily superior to the traditional methods — just that the determination should be made through the competitive process.” The ubiquitous state laws in question were originally put into place to prevent big automakers from establishing distribution monopolies that crowd out dealerships, which tend to be locally owned and family run. They were intended to promote market competition, in other words. But the FTC officials say they worry (as have we at DisCo) that the laws have instead become protectionist, walling off new innovation. “FTC staff have commented on similar efforts to bar new rivals and new business models in industries as varied as wine sales, taxis, and health care,” the officials write in their post. “How manufacturers choose to supply their products and services to consumers is just as much a function of competition as what they sell — and competition ultimately provides the best protections for consumers and the best chances for new businesses to develop and succeed. Our point has not been that new methods of sale are necessarily superior to the traditional methods — just that the determination should be made through the competitive process.”

As Tesla’s CEO Elon Musk noted earlier this year, “the auto dealer franchise laws were originally put in place for a just cause and are now being twisted to an unjust purpose.” Yes, indeed. It is pure rent seeking by obsolescent firms. State and local regulators have eliminated the direct purchasing option by taking steps to shelter existing middlemen from new competition. That’s not at all consumer protection, it is instead economic protectionism for a politically powerful constituency. Thanks to the FTC staff, some brave state legislators may now be emboldened to resist the temptation to decide how consumers should be permitted to buy cars.

Unfortunately, the issue is not limited to automobiles. I wrote recently about how in New York City, officials want to ban Airbnb because its apartment rental sharing service is not in compliance with hotel safety (and taxation) rules. The New York Times last Wednesday editorialized in support of that approach, arguing that Airbnb is reducing the supply of apartments and increasing rents. They’re wrong, of course, because short-term visits obviously do not substitute for years-long apartment leases. But the more important issue is that one economic problem does not justify reducing competition in a separate market. If New York actually has an apartment rent price problem, banning competition for hotels is no more a solution than prohibiting direct-to-consumer auto sales.

Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

Tuesday was a big day in the world of tech-powered disruptive innovation. What the news of April 22nd shows, however, is expanding use of the legal process by incumbent industries to thwart change — and the unfortunately all too frequent concurrence of regulators and courts with that ancient mantra of obsolescent businesses, namely “consumer protection.” Old, entrenched industries frequently lean on their political connections and get the government to come up with some new justification (or recycle an old one) for shutting down upstart rivals or, at the very least, undermining their competitive advantages.

Tuesday witnessed two potentially landmark events, ones that may in time change this familiar paradigm. The first was the morning hearing before the U.S. Supreme Court in ABC v. Aereo, the broadcast networks’ copyright law challenge to the now well-known streaming IPTV start-up. The second, just slightly later in the day, were oral arguments at a New York state court in Albany over whether Airbnb will be permitted to offer its peer-to-peer apartment rental services in New York City, where a 2010 measure meant to curb unregulated hotels prohibits renting out an apartment for less than a month.

The DisCo Project has devoted a series of posts to the Aereo case. Like a Sony Betamax for the 21st century, the Supreme Court is being asked to decide whether moving technology that is lawful for an individual to use on his or her own becomes a copyright violation if offered over the Internet. But the major broadcast networks (like the movie studios who opposed VCR recording in the 1980s) are convinced their entire business model will collapse if Aereo is sanctioned, threatening the nuclear option of stopping over-the-air transmission in favor of all-cable distribution should Aereo prevail.

Airbnb, in contrast, is fighting an effort by New York regulators to collect the names of Airbnb hosts who are breaking the law by renting out multiple properties for short periods. The company, which is now estimated to be worth $10 billion, is framing the dispute as a case of government scooping up more data than it needs for purposes that are vague. What the tussle is really about, of course, is whether the renting public actually needs protection from “unregulated hotels” and, even if true, why Airbnb’s efforts to make a market for DIY rentals is at all harmful. Continue reading Tech Tuesday: Litigation, Legislation and Regulatory Protectionism

Every new year sees a slew of top 5 and top 10 lists looking backwards. Here’s one that looks forward, predicting the five biggest disruptive technologies and threatened industries for 2014.

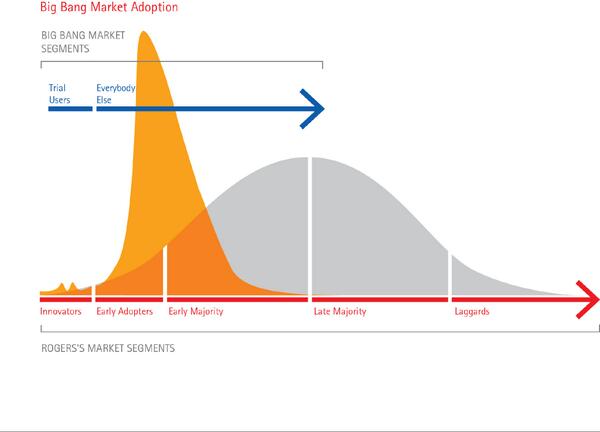

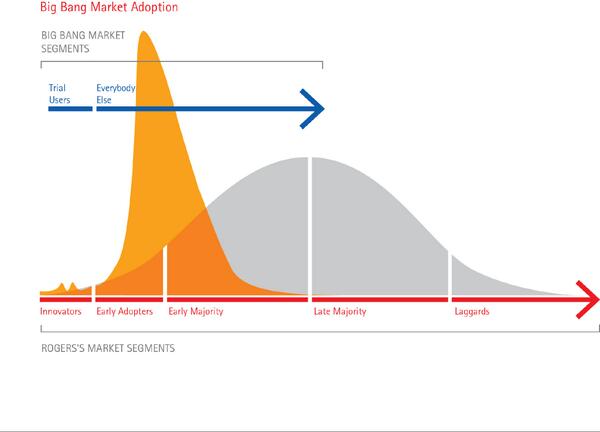

Making projections like these is really hard. Brilliant pundit Larry Downes titles his new book (co-authored with Paul Nunes) Big Bang Disruption: Strategy In an Age of Devastating Innovation. Its thesis is that with the advent of digital technology, entire product lines — indeed whole markets — can be rapidly obliterated as customers defect en masse and flock to a product that is better, cheaper, quicker, smaller, more personalized and convenient all at once.

Since adoption is increasingly all-at-once or never, saturation is reached much sooner in the life of a successful new product. So even those who launch these “Big Bang Disruptors” — new products and services that enter the market better and cheaper than established products seemingly overnight — need to prepare to scale down just as quickly as they scaled up, ready with their next disruptor (or to exit the market and take their assets to another industry).

Disruptors can come out of nowhere and happen so quickly and on such a large scale that it is hard to predict or defend against. “Sustainable advantage” is a concept alien to today’s technology markets. The reputation of the enterprise, aggregated customer bases, low-cost supply chains, access to capital and the like — all things that once gave an edge to incumbents — largely no longer exist or are equally available to far smaller upstarts. That’s extremely unsettling for business leaders because their function is no longer managing the present but inventing the future…all the time.

I certainly have no crystal ball. Yet just as makers of stand-alone vehicle GPS navigation devices were overwhelmed in 2013, suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere, by smartphone maps-app software, e.g., Google Maps, etc., so too do these iconic industries and services face a very real and immediate threat of big bang disruption this year.

Continue reading 5 Industries Facing Disruption In 2014

The U.S. economy has seen its share of disruptive technologies derailed (at least in time-to-market) by archaic legal regimes. Look to Uber’s taxi-hailing service and Airbnb’s apartment rental innovations as recent examples. Most times it’s a case of old assumptions about consumer protection and competition having lost validity with changed circumstances. Other times it’s simple protectionism by legacy incumbents, as in the legal assault on Aereo’s IPTV streaming service for alleged copyright infringement. In the case of electric auto developer Telsa Motors, however, it’s something a little different.

The problem for Tesla’s well-reviewed vehicles — Consumer Reports gave the new Tesla S its highest car rating ever — is not technical, as the California start-up boasts impressive lithium battery innovations and is aggressively building its own chain of recharging stations. Instead the constraint is a plethora of state laws (48 in all) that prohibit or limit automobile manufacturers from selling direct to consumers or owning auto dealerships. These statutes, which date to the 1950s, are matched by a federal law known as the “Automobile Dealers’ Day In Court Act.” That legislation is an anomaly which allows dealers (franchisees) to sue in their home federal district court and recover legal fees if a manufacturer fails to “act in good faith in performing or complying with any of the terms or provisions of the franchise, or in terminating, canceling or not renewing the franchise with said dealer.” (These sorts of lawsuits would otherwise require a minimum of $75,000 at stake, would be governed by state law and would not have the threat of fee-shifting.) The problem for Tesla’s well-reviewed vehicles — Consumer Reports gave the new Tesla S its highest car rating ever — is not technical, as the California start-up boasts impressive lithium battery innovations and is aggressively building its own chain of recharging stations. Instead the constraint is a plethora of state laws (48 in all) that prohibit or limit automobile manufacturers from selling direct to consumers or owning auto dealerships. These statutes, which date to the 1950s, are matched by a federal law known as the “Automobile Dealers’ Day In Court Act.” That legislation is an anomaly which allows dealers (franchisees) to sue in their home federal district court and recover legal fees if a manufacturer fails to “act in good faith in performing or complying with any of the terms or provisions of the franchise, or in terminating, canceling or not renewing the franchise with said dealer.” (These sorts of lawsuits would otherwise require a minimum of $75,000 at stake, would be governed by state law and would not have the threat of fee-shifting.)

Continue reading Want A Tesla? You Can’t Buy One Here.

People have been talking, and pontificating, about a coming “Internet of Things” since 1999. The idea is that the many sensors, actuators and digital data recorders in the environment around us — like the electronic control units (ECUs) in modern automobiles — will be uniquely identified and connected via IP to each other and to the world. This would allow instantaneous supply chain fulfillment, green initiatives like demand-side management and smart refrigerators, as well as simply cool stuff that puts remotely programming one’s DVR from a smartphone app to shame. As McKinsey & Co. noted in 2010:

The physical world itself is becoming a type of information system… When objects can both sense the environment and communicate, they become tools for understanding complexity and responding to it swiftly. What’s revolutionary in all this is that these physical information systems … work largely without human intervention.

So what’s going on? Two things. The obvious one is that more than a decade later (and despite the fact that by 2008 there were already more “things” connected to the Internet than people in the world) we are still not “there” yet. Refrigerators cannot detect when the last soda can is used, let alone order more autonomously; HVAC systems largely cannot interact with electricity genitors in real time to consume more energy when rates are lower, and vice-versa; and suitcases cannot communicate with airport luggage systems to tell the machines onto which flight they should be loaded (except with barcode readers). Partially, that’s because technologists frequently overstate adoption projections for new networks by 10 years or more. Less obvious is that there’s been a quiet push in the European Union (EU) to regulate the IoT even before it is fully gestated and born.

A European Commission “consultancy” on the Internet of Things was launched in 2008. By 2009 the EU had already issued an Action Plan for Europe for the IoT, which concluded:

Although IoT will help to address certain problems, it will usher in its own set of challenges, some directly affecting individuals. For example, some applications may be closely interlinked with critical infrastructures such as the power supply while others will handle information related to an individual’s whereabouts. Simply leaving the development of IoT to the private sector, and possibly to other world regions, is not a sensible option in view of the deep societal changes that IoT will bring about.

As a result, libertarian business groups such as the European-American Business Council and TechAmerica Europe have this summer come out in opposition to the EU’s approach, pressing for industry-led standards and application of existing measures, like the existing EU data protection rules (which already exceed the United States’ by a wide margin), “in lieu of a new regulatory structure.”

This is a scary prospect. That the EU would even consider crafting a regulatory scheme now for a technology revolution that realistically remains years away, requires immense levels of cooperation among industries, and holds the potential to transform business and life as we know it, is remarkable. Remarkable because such a philosophy is so alien to American economic values and to the spirit of innovation and entrepreneurship that launched the commercial Internet and Web 2.0 revolutions.

This article is not the place to debate the conflicts, trade-offs and differing views of government animating current technology policy issues like net neutrality, privacy and cybersecurity, copyright and the like. The reality though, is that issues such as those are generally being assessed within a spectrum of solutions, worldwide, which reflect known risks and benefits, some proposals of course being more interventionist than others. But that is far different from allowing a single bureaucratic monolith to dictate the shape of an industry and technology that remains embryonic. How is it even possible to develop fair rules for the IoT when no one has any real idea what or when it will be?

More than 15 years ago, this writer worked for one of his corporate clients on a legislative amendment offered by Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-Cal.) to the Telecommunications Act of 1996. The so-called “Eshoo Amendment,” designed to limit the role of the Federal Communications Commission in mandating standards for emerging, competitive digital technologies like home automation, passed. The irony, of course, is that at the time Congresswoman Eshoo analogized home automation to a future world like that of The Jetsons. Now 16 years down the road, we are barely closer to George, Elroy and their flying cars, robotic maids and the like than we were then. More than 15 years ago, this writer worked for one of his corporate clients on a legislative amendment offered by Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-Cal.) to the Telecommunications Act of 1996. The so-called “Eshoo Amendment,” designed to limit the role of the Federal Communications Commission in mandating standards for emerging, competitive digital technologies like home automation, passed. The irony, of course, is that at the time Congresswoman Eshoo analogized home automation to a future world like that of The Jetsons. Now 16 years down the road, we are barely closer to George, Elroy and their flying cars, robotic maids and the like than we were then.

But that ’96 effort illustrated a fundamental difference between the United States and the European Union about the proper role of government with respect to innovation. The EU subsidizes research, sets agendas and looks to intervene in the marketplace in order to establish rules of the road even before new industries are launched. The US sits back, lets the private sector innovate, and generally intervenes only when there has been a “market failure.” That’s a philosophy largely embraced by both major American parties regardless of the increasingly polarized political landscape in Washington, DC.

This basic difference in world views between the home of the Internet and European regulators — as true today as in 1996, if not more so — could doom the Internet of Things. So if you are a fan of future shock, then it’s clear you should not react to the EU’s efforts to shape the IoT with a viva la difference attitude. The difference is dangerous to innovation and especially dangerous to disruptive innovation. It’s no wonder that few real digital innovations have come from Europe. Don’t expect many in the future unless the EU finds a way to decentralize and privatize its bureaucratic tendency towards aggrandizing government in the face of what IoT experts anticipate will be “a small avalanche of disruptive innovations.”

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

One year ago, the Wall Street Journal and other business publications reported that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) had launched an investigation into “Twitter and the way it deals with the companies building applications and services for its platform.” The gist of the apparent competitive concern was that Twitter — which has grown from nothing to a significant new medium of social communications in just five years — had decided to limit access to its application programming interfaces (APIs) for third-parties, such as HootSuite, Echofon and the like, selling Twitter “client” software.

There’s no doubt Twitter is a disruptive technology. Of course, in 2000 the FTC was so convinced that an AOL-Time Warner combination would monopolize Internet content that it saddled the then-biggest merger with an onerous consent decree that evaporated, as did AOL itself, in the relative blink of an eye. Now it appears the agency is making the same mistake again. Assuming that a new and evolving technology represents a stand-alone market for antitrust purpose is dangerous where disruptive entrants are concerned, because as AOL illustrates, despite a first-mover advantage, even in network effects markets that may “tip” to a single firm competitive reality changes more quickly and in ways even the brightest pundits and government policy makers could never predict.

Given that Twitter is in competition with Facebook, LinkedIn, Tumblr, Pinterest, Instgram and many other social networking and messaging services, including the near-moribund Google+, you’ve got to wonder why the FTC could even plausibly hypothesize that Twitter has anything approaching monopoly power. One can perhaps understand policy neophytes like Mike Arrington naively saying that Twitter has a “microblogging monopoly,” but not seasoned antitrusters. Given that Twitter is in competition with Facebook, LinkedIn, Tumblr, Pinterest, Instgram and many other social networking and messaging services, including the near-moribund Google+, you’ve got to wonder why the FTC could even plausibly hypothesize that Twitter has anything approaching monopoly power. One can perhaps understand policy neophytes like Mike Arrington naively saying that Twitter has a “microblogging monopoly,” but not seasoned antitrusters.

Twitter management explained at the time that “Twitter is a network, and its network effects are driven by users seeing and contributing to the network’s conversations. We need to ensure users can interact with Twitter the same way everywhere.” That’s a quintessential business judgment by corporate managers who presumably know their users (tweeters) and customers (advertisers) best. The company’s motivation is also clear and perfectly valid: it doesn’t want third parties making money — namely, coming into direct rivalry by selling ads — off its service, and thus depriving Twitter of potential revenue. It is incontestable that Twitter could vertically integrate into the client software business itself (a first step in which it did by acquiring TweetDeck), without any possible antitrust constraints. In this light, what could conceivably be wrong with Twitter setting ground rules that require third-party providers to utilize a common user interface (UI) scheme?

As Adam Thierer of the Technology Liberation front observed in 2011:

This episode again reflects the short-term, static snapshot thinking we all too often see at work in debates over media and technology policy. That is, many cyber-worrywarts are prone to taking snapshots of market activity and suggesting that temporary patterns are permanent disasters requiring immediate correction. Of course, a more dynamic view of progress and competition holds that “market failures” and “code failures” are ultimately better addressed by voluntary, spontaneous, bottom-up responses than by coercive, top-down approaches

Ironically, the Twitter decision to control API usage and effectively boot off some third-party software had only one economic effect. It cannibalized Twitter’s own developer and partner ecosystem, on which the company had relied heavily through its first years of extraordinarily rapid growth, in favor of an internal solution. That decision alienated some Twitter users and almost certainly reduced the absolute number of tweets sent and received — and thus the page views on which Twitter’s advertising rates are necessarily based. It also risked alienating the venture capitalists who have invested an estimated $475 million over just one-half of a year in companies working to develop Twitter-compatible apps and utilities. So the only firm Twitter is really hurting by this practice is Twitter itself. Eating your own ecosystem is hardly the stuff of monopolization.

Sacrificing independent distribution in favor of vertical integration is also a business model companies adopt and reject like roller coasters. In the oil industry, for instance, the most famous government antitrust case of them all is 1911’s Standard Oil, which broke up the vertically integrated petroleum monopoly assembled by John D. Rockefeller. Today, Standard’s offspring are rapidly disintegrating, divesting both wholesale distribution of refined oil products and retail gasoline dealerships. Sometimes conventional business wisdom extols vertical integration, other times it emphasizes an Adam Smith-type comparative advantage. But isn’t that the essence of marketplace competition? And in turn isn’t that something our nation’s competition policy should leave in the hands of market participants rather than government agencies?

The answer from Forbes is a simple yes:

If the FTC is indeed investigating Twitter, they are likely to find this case pretty boring. In acquiring the third party apps widely adopted by its users, Twitter is simply making a gradual, not to mention inevitable, move closer to its customer base. The startup is often slammed for its struggle to adopt a serious business model. Now that Twitter has finally figured out it is awfully difficult to build a business as a plumbing conduit, suddenly it’s lambasted as the next Microsoft.

In fact, the issue here is far more significant for technologies down the road that no one has as yet even conceived. Twitter seems sufficiently well-established that it will likely survive an FTC investigation, at least in the short run, and however misguided the government’s underlying assumptions may be. But start-ups which have not yet escaped from private betas and coders’ college dorm rooms will give pause, as they grow, before deciding to sever relations with partners  that helped them “get big fast.” The fear is that cutting off downstream firms, even if taken for objectively valid business reasons, will catalyze an FTC or European Union antitrust investigation of whether the firm has “abused” its “market dominance.” that helped them “get big fast.” The fear is that cutting off downstream firms, even if taken for objectively valid business reasons, will catalyze an FTC or European Union antitrust investigation of whether the firm has “abused” its “market dominance.”

A threat of government action can be just as debilitating to innovation as premature enforcement intervention into the marketplace. Let’s hope the FTC’s 2011 Twitter investigation is mothballed in 2012, and that in the future investigations of segment-leaders in nascent technology spaces are opened only where — unlike the case of Twitter — there’s clearly an economically valid market and practices involved which are unambiguously anticompetitive. The FTC has said nothing about the Twitter issue for a year, while the San Francisco Examiner revealingly comments that “[i]n the space of [that] year, the FTC has racked up more legal action involving the high tech world than the FCC and both houses of Congress combined.” Note to Chairman Leibowitz: it’s time to let this one go, now. If your agency wants to do that quietly in order to save face, no one in Silicon Valley will mind at all. We won’t tell.

Note: Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

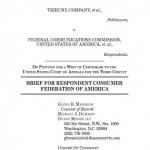

This is the brief I just prepared for the Consumer Federation of America to the U.S. Supreme Court on the issue of whether the so-called Red Lion doctrine of First Amendment regulation of broadcasters should be re-examined. My favorite passage is:

[T]he presumption of invalidity inherent in petitioners’ argument is flawed. Broadcasters do not remain “singularly constrained,” Pet. at 16, on the ground that there were few speakers 45 years ago. When Red Lion was decided there were hundreds more newspapers in America, half a dozen or more in major cities like New York, national, weekly news and cultural magazines (Life, Look, etc.) and many other sources of information and entertainment that are no longer available in today’s marketplace. Therefore, the “undeniably large increase in the number of broadcast stations and other media outlets” on which the D.C. Circuit and petitioners rely, id. at 18, is immaterial to the economic regulation of broadcast licensees unless — as petitioners dare not suggest, because it is untrue — the increase has lessened the technical need for governmental entry and interference regulation.

Whether there are three or six or ten television stations in a local market, however, does not at all mean there is enough spectrum to accommodate everyone who would like to use the airwaves. What some judges have called “the indefensible notion of spectrum scarcity,” Action For Children?’s Television v. FCC, 105 F.3d 723, 724 n.2 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (Edwards, J., dissenting), is therefore totally true and completely defensible.

[slideshare id=11925599&doc=11-696cfaopp-brief-120308132113-phpapp02&type=d]

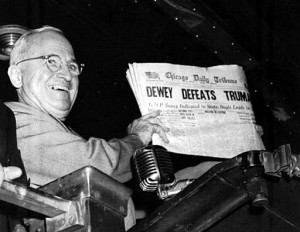

60 years ago, when Harry Truman beat Tom Dewey for the presidency, it was widely predicted by pollsters that Truman would lose. This led to the famous “Dewey Beats Truman” headline in the newspaper proudy flashed by the winning candidate.

The problem, it was later revealed, was that the Gallup organization based its poll results on responses to telephone inquiries. But in the late 1940s, that selection inevitably favored wealthier Republicans, leading to skewed poll results.

Gallup is best known for that one half-century-old blunder. There’s a terrible irony in that. The studious George Gallup did more than anyone to put opinion polling on solid ground.

We have a similar problem today, it appears to me. While telephone subscribership has now become ubiquitous, increasingly many citizens — especially twenty-somethings — no longer use landline telephones, instead going completely wireless. The proportion was 1 in 6 three years ago and continues to increase steadily. Pollsters, however, still base their surveys on landline phone subscribers. In fact, under FCC regulations it is unlawful to telephone a wireless subscriber for a “solicitation” or using an autodialer (a technical prerequisite to modern polling) without either their consent or a prior business relationship. Therefore, despite a non-profit exemption in the FCC’s rules (which, unlike the Federal Trade Commission’s “telemarketing sales rule,” do not expressly exempt political polling), the law is standing in the way of accurate political predictions.

How this will play out in next Tuesday’s elections is unclear to me, as I claim no special expertise in political punditry. But it is revealing that the problems experienced in 1948 are recurring today in a different form due to technological change and the accelerating proliferation of wireless communications devices.

Several of the previous posts in my The Law of Social Media essay series focus on core legal issues, such as copyright in user-generated content and employer use of social media for HR decisions. This one is a bit different. Like John Naisbitt, it describes what I am convinced are the most significant law/policy “megatrends” affecting the social media space today.

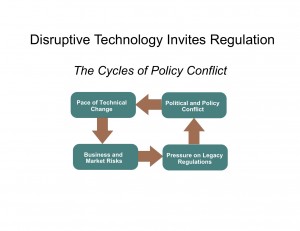

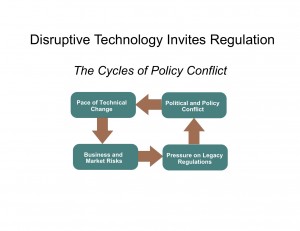

As an overview, consider the following scenario—and click for a larger image:

As the graphic indicates, the reality is that disruptive technologies quickly and visibly invite governmental regulation. That’s because change creates business and policy risks, which threaten legacy products and powerful business incumbents, and in turn which cause political pressures to protect established constituencies. Since social media is most assuredly a disruptive force, this circular pattern will likely manifest itself — in fact, as I discuss below it already has — in public policies towards social media and social networking communications.

1. Censorship & Filtering

Governments absolutely hate “unfiltered” social media and will move to censor and control it.

In the East, the basis for such censorship is political and religious oppression, as in Iran, North Korea, China, etc. In the West, the more unlikely culprit has been intellectual property (e.g., music and movie copyrights) and obscenity, as in Australia, France and New Zealand’s efforts to install country-wide porn filters and institute a “the strikes” rule against P2P file sharing. And everywhere, government mourns the loss of the historic financial and advertising basis for traditional media like newspapers and broadcast television, proposing to bail out or subsidize the latter in order to prevent social media from achieving dominance at the expense of last century’s communications technologies. Censorship is far from dead on the Web; in fact, it’s really only beginning.

2. Privacy

The EU’s strict data protection (privacy) regime will spread and overtake the US opt-out approach.

Most everyone knows that the European Union has a highly protective scheme of individual privacy in the digital age. Fewer understand that in the United States, with the exception of specially regulated industries like health care and financial services, the only privacy protections available are basically those the Constitution provides as against the government. That will change, however. The EU is too large a market for businesses to overlook, commerce today is fully globalized and while the United States remains the least privacy-centric of any major industrialized nation, that is changing as legislators and regulators more often choose an opt-in requirement for newer, albeit still infrequent, electronic privacy measures.

3. Criminal Law

Cyber offenses will (finally) be created.

In the past, criminal violations involving the Internet and online activities have largely focused on corporate interests, like the Anti-Cybersquatting, CFAA and CAN-SPAM Acts. But the current proliferation of pedophilia, cyber-bullling, stalking and other socially offensive digital-centric conduct is different. Many times, existing criminal laws — for instance, of assault — are not broad enough to cover online conduct. Other time, prosecutors are reluctant to indict and juries even more reluctant to convict. Yet the US congressional approach to indecency on the Web has for more than a decade been to attempt to ban conduct deemed seedy, whether pornography or gambling, to avoid having the “new” media infected with perceived old evils, for instance the Communications Decency Act of 1996. As a result, there is a good chance, well above 50% in my estimation, that the next several years will bring a proliferation of state and federal laws making criminally unlawful specific forms of online activity deemed socially deviant or harmful.

4. Anonymity

Anonymity on the Internet is under assault and may be lost.

A timely prediction, given that just yesterday two different courts compelled the unmasking of anonymous commenters in civil pretrial discovery—when the posters were not even parties to the cases. Ninth Circuit Upholds Unmasking of Online Anonymous Speakers and Illinois Appellate Court Unmasks Anonymous Commenters. There are a variety of reasons, but the principal one is that by defeating anonymity, politicians can be seen as “protecting” the victims of Web-based schemes, involving both antisocial (i.e., bullying, extortion, etc.) and anti-consumer (i.e., stock pump-and-dump chats, etc.) behavior, which sometimes end quite tragically, as in teenage suicides. This is reinforced by the continuing efforts of copyright holders (music, photos, video, news) to require ISPs to disgorge the identities of infringing users and by the FTC’s sponsored blogging “guidelines,” which support the theme of transparency from a consumer protection perspective. Almost alone among nations, only America has a Tom Paine and Federalist Papers/Primary Colors tradition of anonymous or pseudonymic political speech, yet even here — unless the Supreme Court intervenes — short-term passions, politics and national security phobias almost always trump free speech. The old proverb was that “No one knows if you are a dog on the Internet.” Don’t plan on barking much longer!

5. Competition

Competition and antitrust laws will reshape social media providers.

My core training is in antitrust law, although this megatrend has little to do with yours truly. Instead, it stems from the reality that Facebook, Apple and Google, among others, are already facing competition law investigations in the advertising, mobility, search and handset markets. From an economic perspective, there are very strong, positive network effects in social media, far greater than were true in the 1990s for Microsoft’s WIndows OS. As a consequence, viral expansion leads to small social media companies getting VERY big VERY fast: witness Facebook’s 500 million users and Twitter’s phenomenal hockey-stick growth curve. It is difficult for entrepreneurs to shake the old underdog mentality even when their companies become big enough that market power makes their business practices and acquisitions suspect, as Mark Zuckerberg is now learning to his chagrin. And when fueled by financial underwriting from legacy competitors — the dark political underbelly of Washington, DC and Brussels, Belgium antitrust battles — the “nascent” stucture of social media and wireless markets has, to date, not proven sufficient to keep the mitts of antitrusters from the US Department of Justice and the EU’s Competition Directorate from meddling—e.g., Google/Yahoo (2008-09) and Oracle/Sun (2009-10), to name a couple of examples.

6. Location

Location-bsed services will spawn a host of new policy battles.

“Location, location, locations” is not just a real estate slogan, it’s the cross-hairs for a number of policy trends affecting social media. The indicia are not found not just in the geometrically increasing popularity of geo-tagged photos, location check-in apps and games, and the like, but as well and perhaps more importantly in the fact that as wireless communications and data come to dominate telecom — a direct consequence of social networking — regulatory oversight follows almost automatically. “Nomadic” services like VoIP and video chart (e.g., FaceTime), in contrast, present an equally great threat to the established order by making location a matter of indifference. At bottom, this is an industry where eyeballs and advertising dollars still rule. So as marketers devise ever-clever ways to monetize users’ location (including the launch this week of my client shopkick’s location marketing app) all of the bad stuff that can happen online is bound, eventually, to arise with respect to location-based services. LBS isn’t bad; some people are bad. Unfortunately for the FourSquares and Gowallas of the social media world, that has never been enough in most societies to stop gun control—and it won’t be enough to arrest the coming push for consumer protection and marketing regulation in the location services space.

Note: I first used the “megatrends” metaphor while presenting at the 140 Characters Conference-DC (#140onf-dc) in June 2010, and am indebted to organizer Jeff Pulver for serving as my muse for these thoughts. Thanks, Jeff!

|

|