A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

Recently the United States federal antitrust enforcement agencies — the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division — issued a joint policy statement designed to “make it clear that they do not believe that antitrust is, or should be, a roadblock to legitimate cybersecurity information sharing.” The release made headlines globally, but the real story is that the risk of antitrust exposure for exchange of cyber risk information, even among direct competitors, was and remains almost non-existent.

That is because the U.S. antitrust laws (principally Section 1 of the Sherman Act) prohibit horizontal conspiracies and agreements among rivals, like price fixing, that harm competition. In some areas, information exchange can be competitively problematic, for instance where firms share non-public bidding or price data, or M&A transactions where the deal parties “gun jump” by acting as if they were already merged instead of continuing to compete independently. Yet as the policy statement confirmed, “cyber threat information typically is very technical in nature and very different from the sharing of competitively sensitive information such as current or future prices and output or business plans” and is thus “highly unlikely to lead to a reduction in competition.”

That’s hardly new. More than a decade ago DOJ said exactly the same thing in approving a proposal for cybersecurity information sharing in the electric industry, and Antitrust Division chief Bill Baer called the 2014 reaffirmation “an antitrust non-brainer.” But perceptions can have consequences, and some had voiced the fear that the exchange of IT security information among competitors could present a slippery slope, a forum for the kind of hard-core anticompetitive agreements the government loves to prosecute. At least that is what the White House, which called antitrust law “long a perceived barrier to effective cybersecurity,” reasoned in encouraging the FTC-DOJ clarification. So clearing away the underbrush of misinformation should help reassure business executives that companies which share technical cybersecurity information such as indicators, threat signatures and security practices, and avoid exchanging competitively sensitive information like business plans or prices, will simply not run afoul of the antitrust laws.

Continue reading Cybersecurity & Antitrust

I’ve spent a fair amount of time at Project DisCo discussing how political, legal and regulatory processes in the United States are largely biased against disruptive innovators in favor of legacy incumbents. That’s typically just as true for Uber and its ride-hailing competitors as it is for Aereo, Hulu, Netflix and other streaming video — or over the top (“OTT”) — Internet television services. But perhaps no longer.

The Consumer Choice in Online Video Act (S.1680), introduced by Sen. Jay Rockefeller, chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee, aims to change things. The legislation’s stated objectives are to “give online video companies baseline protections so they can more effectively compete in order to bring lower prices and more choice to consumers eager for new video options” and to “prevent the anticompetitive practices that hamper the growth of online video distributors.” It does so by (a) requiring television content owners to negotiate Internet carriage arrangements with OTT providers in good faith, (b) guaranteeing such firms reasonable access to video programming by limiting the use of contractual provisions that harm the growth of online video competition, and (c) empowering the FCC to craft regulations governing the program access interface between online providers and traditional television networks and studios.

S.1680 is a remarkable legislative effort to predict where the nascent online programming market is headed. It anticipates that in order to fulfill their competitive potential, OTT video entrants will require similar legal protections to what satellite television providers have for years enjoyed. The bill applies the program access model developed several decades ago for satellite television to the new world of OTT video.

As Rockefeller explained:

[He] has watched as the Internet has revolutionized many aspects of American life, from the economy, to health care, to education. It has proven to be a disruptive and transformative technology, and it has forever changed the way Americans live their lives. Consumers now use the Internet, for example, to purchase airline tickets, to reserve rental cars and hotel rooms, to do their holiday shopping. The Internet gives consumers the ability to identify prices and choices and offers an endless supply of competitive offerings that strive to meet individual consumer’s needs.

But that type of choice — with full transparency and real competition — has not been fully realized in today’s video marketplace. Rockefeller’s bill addresses this problem by promoting that transparency and choice. It addresses the core policy question of how to nurture new technologies and services, and make sure incumbents cannot simply perpetuate the status quo of ever-increasing bills and limited choice through exercise of their market power.

Modeled explicitly on the controversial 1992 Cable Act (which itself passed only over a presidential veto), S.1680 appears to be the first piece of legislation embracing disruption as a procompetiitive form of market evolution, including as its initial congressional “finding” that OTT services have the potential to “disrupt the traditional multichannel video distribution marketplace.” That’s excellent. At the same time, the bill’s choice of solution is contentious, by subjecting vertically integrated cable and television providers (e.g., Comcast-NBCu) to another regime of program access and retransmission mandates. The legal standard fashioned for testing the validity of a television distribution contract in S.1680 is whether it “substantially deters the development of an online video distribution alternative.” Given the highly visible retransmission disputes that have arisen in recent months, such as the Tennis Channel and CBS, plus the lack of evidence that vertical integration in fact provides an incentive for exclusive dealing and content foreclosure, free market advocates are likely to object to this. Proponents of net neutrality rules, especially where data caps are concerned, have already spoken out in support.

Continue reading OTT Disruption: Is the “Rockefeller Bill” the Answer?

Late Friday afternoon, several stories appeared quoting unnamed sources that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has received a staff memo recommending an antitrust prosecution of Google. Now, in a letter just days ago to FTC Chairman Jon Leibowitz, Colorado Rep. Jared Polis — founder of bluemountain.com and ProFlowers.com — counseled that an FTC monopolization case against Google could lead to legislative blowback.

I believe that application of antitrust against Google would be a woefully misguided step that would threaten the very integrity of our antitrust system, and could ultimately lead to congressional action resulting in a reduction in the ability of the FTC to enforce critical antitrust protections in industries where markets are being distorted by monopolies or oligopolies.

Google Antitrust Action Could Cost FTC Power, Dem Warns | Law360. That’s consistent with what I suggested in my five-part series Why An FTC Case Against Google Is A Really Bad Idea, but of course goes even further as my legal analysis did not address potential political or legislative reaction to a formal FTC complaint.

Meanwhile, commentators are whacking each other silly. Sam Gustin observed in TimeBusiness that “Microsoft and its anti-Google allies have spent untold millions waging an overt and covert campaign designed to persuade regulators to hobble the search leader. Perhaps if these companies spent a little less time complaining and a little more time innovating, they’d have a better chance of competing in the marketplace.” In response, John Paczkowski at AllThingsDigital noted the Polis letter’s “fortuitous timing” and implied that it “seems a bit odd” for a junior legislator to threaten a sitting FTC chairman, concluding that “maybe we should all wait and see the FTC’s evidence and the merits of its case — if there is one — before threatening to limit the agency’s authority.”

It is clear to any objective observer that there is a case in the works and that the FTC, which on background leaked that four of five commissioners are already on board, sent a trial balloon out through the press last week. Paczkowski is naive if he believes the timing of the stories last Friday was also not “fortuitous” or that the “merits” of the FTC’s case may not properly be a matter of policy and political debate. Having witnessed this same pas de deux for years in connection with United States v. Microsoft Corp., it’s just business as usual in Washington, DC. That may not make it right or courteous, but it does make it completely unexceptional.

So much media attention was paid to the spectacular collapse of U.S. Senate deliberations on a cybersecurity bill in August — and the Obama Administration’s controversial move to fashion an Executive Order on the subject — that few if anyone focused on the biggest change affecting the data protection landscape. The Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) guidelines on disclosure of cyber attacks by publicly traded corporations have become de facto rules for at least six companies, including Google Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., according to recent agency enforcement letters.

Last fall, the SEC completed a long process of issuing staff “guidance” on when cybersecurity risks must be disclosed in public company securities filings (annual reports, 10Qs, etc.). The sensible conclusion was that if a hack or intrusion would be “material” to an ordinary investor, corporations need to disclose the cyber risk and discuss their actions to ameliorate or prevent it. Unlike Y2K, however, these guidelines, released by the SEC’s corporate finance section, did not come with a “safe harbor” for disclosing companies. In 1999, congressional legislation created a legal safety zone for Y2K disclosures, avoiding liability under the Securities Act of 1934, that has not been replicated with respect to more general cybersecurity risks. Last fall, the SEC completed a long process of issuing staff “guidance” on when cybersecurity risks must be disclosed in public company securities filings (annual reports, 10Qs, etc.). The sensible conclusion was that if a hack or intrusion would be “material” to an ordinary investor, corporations need to disclose the cyber risk and discuss their actions to ameliorate or prevent it. Unlike Y2K, however, these guidelines, released by the SEC’s corporate finance section, did not come with a “safe harbor” for disclosing companies. In 1999, congressional legislation created a legal safety zone for Y2K disclosures, avoiding liability under the Securities Act of 1934, that has not been replicated with respect to more general cybersecurity risks.

The recent SEC enforcement steps also have taken place at the corporate finance division level, but presumably with the informal approval at least of SEC Chair Mary Schapiro. In these cases, the agency “requested” that a number of large Internet companies clarify or modify their SEC filings to disclose cyber incidents that previously had not been reported to investors. In April, the SEC asked Amazon to disclose in its next quarterly filing that hackers had raided its Zappos.com unit, stealing addresses and some credit card digits from 24 million customers in January, which Amazon did. Google likewise agreed in May to put a previously disclosed cyber atack in its formal earnings report. AIG, Hartford Financial Services Group, Eastman Chemical and Quest Diagnostics were also asked to improve disclosures of cyber risks, according to agency staff correspondence reported by Bloomberg News.

As one example, here is the relevant excerpt from the corporate finance staff’s May 2, 2012 letter to Google CEO Larry Page:

We note your disclosure that if your security measures are breached, or if your services are subject to attacks that degrade or deny the ability of users to access your products and services, your products and services may be perceived as not being secure, users and customers may curtail or stop using your products and services, and you may incur significant legal and financial exposure. We also note your Current Report on Form 8-K filed January 13, 2010 disclosing that you were the subject of a cyber attack. In order to provide the proper context for your risk factor disclosures, please revise your disclosure in your next quarterly report on Form 10-Q to state that in the past you have experienced attacks. Please refer to the Division of Corporation Finance’s Disclosure Guidance Topic No. 2 at http://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/guidance/cfguidance-topic2.htm for additional information.

The difference between fall 2011 and spring 2012 is that, irrespective of the formal legal effect of staff guidance, the SEC is using its administrative processes to produce a disclosure result not specifically compelled by the agency’s rules for corporate securities filings. That in itself is not surprising, since the securities laws and implementing SEC regulations are broad enough to encompass any factor, whether financial or otherwise, that could affect stock prices. Here, the SEC staff opined in its guidance that basic SEC rules about market manipulation, insider trading and misleading shareholders (e.g., Rule 10b-5) required disclosure of cyber incidents and cybersecurity risks by any business potentially affected by hacking. And that’s obviously not confined to online retailers or Web-centric businesses.

The bigger question is how businesses can protect themselves from the embarrassment of such compelled, government-mandated cyber disclosures and the even greater potential for fines and formal enforcement actions the SEC may utilize in the IT security realm going forward. Here are a few pointers:

- Do not assume that merely because your business is not online, cybersecurity cannot affect the company. Hundreds of “brick and mortar” retailers, for instance, have had consumer credit card records breached.

- Treat data security just like your securities lawyers treat any other risk to the business’s future, since that is how federal regulators view cyber risks.

- Do not assume the SEC’s focus on cybersecurity is limited to public companies, because the underlying rules cited by its corporate finance division apply just as much to private placements as they do to proxy solicitations and 10K reports.

- When disclosing IT security risks, make sure they are balanced by something concrete and proactive to prevent, or diminish the severity of, cyber attacks. Otherwise diclosures may have the opposite effect of encouraging shareholder class action litigation.

- Work closely with compliance counsel, IT technology experts and your insurance carriers to develop workable cybersecurity assessment and intrusion notification regimes, internally and externally. This should not only reduce legal exposure, but going forward lower the company’s costs for cyber insurance. Periodic outside reviews should provide both comfort and legal protection to CEOs or CFOs signing SEC submissions.

These SEC staff actions were balanced by the traditional caveat that “our comments or changes to disclosure in response to our comments do not foreclose the Commission from taking any action with respect to the company or the filings and the company may not assert staff comments as a defense in any proceeding initiated by the Commission or any person under the federal securities laws of the United States.” But the chances the full SEC would prosecute a public company for following staff suggestions are remote. On the other hand, for public corporations that ignore this lesson, and fail to disclose cybersecurity risks, we suspect only pain and expense — most likely in a Commission prosecution or fine — lie in their SEC futures. So rules are really rules, even when they are not.

Note: Originally written for and reposted with permission of my law firm’s Information Intersection blog.

This is the opening paragraph of an article by this author appearing today in the Fall 2010 issue of Icarus, the newsletter of the ABA’s Communications & Digital Technology Industries Committee, Section of Antitrust Law. “If the issue of broadband reclassification is not addressed with sensitivity to the history and traditions of FCC common carrier regulation, one can all too easily arrive at conclusions that simply cannot be squared with the legal framework applied to telecommunications for more than 30 years.”

The highly polarized debate over so-called net neutrality at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) exposes serious philosophical differences about the appropriate role of government in managing technological change. Neither side is unfortunately free either from hyperbole or fear-mongering. And neither side is completely right.

Read the whole essay. It’s provocative.

Note: I have not appeared as counsel for any party to the FCC’s current net neutrality NOI proceeding and was not paid to write this essay (despite what my colleagues and clients in the public interest community may claim). I represented Google in the past but now am ethically precluded from doing so because my law firm has a conflict of interest, being adverse to Google in an employment age discrimination case before the California Supreme Court. The article nonetheless does not reflect the views or opinions of my firm or any of my clients, past or present.

Several of the previous posts in my The Law of Social Media essay series focus on core legal issues, such as copyright in user-generated content and employer use of social media for HR decisions. This one is a bit different. Like John Naisbitt, it describes what I am convinced are the most significant law/policy “megatrends” affecting the social media space today.

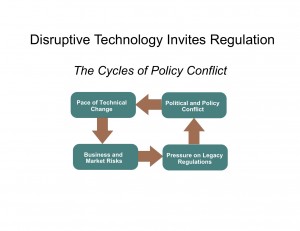

As an overview, consider the following scenario—and click for a larger image:

As the graphic indicates, the reality is that disruptive technologies quickly and visibly invite governmental regulation. That’s because change creates business and policy risks, which threaten legacy products and powerful business incumbents, and in turn which cause political pressures to protect established constituencies. Since social media is most assuredly a disruptive force, this circular pattern will likely manifest itself — in fact, as I discuss below it already has — in public policies towards social media and social networking communications.

1. Censorship & Filtering

Governments absolutely hate “unfiltered” social media and will move to censor and control it.

In the East, the basis for such censorship is political and religious oppression, as in Iran, North Korea, China, etc. In the West, the more unlikely culprit has been intellectual property (e.g., music and movie copyrights) and obscenity, as in Australia, France and New Zealand’s efforts to install country-wide porn filters and institute a “the strikes” rule against P2P file sharing. And everywhere, government mourns the loss of the historic financial and advertising basis for traditional media like newspapers and broadcast television, proposing to bail out or subsidize the latter in order to prevent social media from achieving dominance at the expense of last century’s communications technologies. Censorship is far from dead on the Web; in fact, it’s really only beginning.

2. Privacy

The EU’s strict data protection (privacy) regime will spread and overtake the US opt-out approach.

Most everyone knows that the European Union has a highly protective scheme of individual privacy in the digital age. Fewer understand that in the United States, with the exception of specially regulated industries like health care and financial services, the only privacy protections available are basically those the Constitution provides as against the government. That will change, however. The EU is too large a market for businesses to overlook, commerce today is fully globalized and while the United States remains the least privacy-centric of any major industrialized nation, that is changing as legislators and regulators more often choose an opt-in requirement for newer, albeit still infrequent, electronic privacy measures.

3. Criminal Law

Cyber offenses will (finally) be created.

In the past, criminal violations involving the Internet and online activities have largely focused on corporate interests, like the Anti-Cybersquatting, CFAA and CAN-SPAM Acts. But the current proliferation of pedophilia, cyber-bullling, stalking and other socially offensive digital-centric conduct is different. Many times, existing criminal laws — for instance, of assault — are not broad enough to cover online conduct. Other time, prosecutors are reluctant to indict and juries even more reluctant to convict. Yet the US congressional approach to indecency on the Web has for more than a decade been to attempt to ban conduct deemed seedy, whether pornography or gambling, to avoid having the “new” media infected with perceived old evils, for instance the Communications Decency Act of 1996. As a result, there is a good chance, well above 50% in my estimation, that the next several years will bring a proliferation of state and federal laws making criminally unlawful specific forms of online activity deemed socially deviant or harmful.

4. Anonymity

Anonymity on the Internet is under assault and may be lost.

A timely prediction, given that just yesterday two different courts compelled the unmasking of anonymous commenters in civil pretrial discovery—when the posters were not even parties to the cases. Ninth Circuit Upholds Unmasking of Online Anonymous Speakers and Illinois Appellate Court Unmasks Anonymous Commenters. There are a variety of reasons, but the principal one is that by defeating anonymity, politicians can be seen as “protecting” the victims of Web-based schemes, involving both antisocial (i.e., bullying, extortion, etc.) and anti-consumer (i.e., stock pump-and-dump chats, etc.) behavior, which sometimes end quite tragically, as in teenage suicides. This is reinforced by the continuing efforts of copyright holders (music, photos, video, news) to require ISPs to disgorge the identities of infringing users and by the FTC’s sponsored blogging “guidelines,” which support the theme of transparency from a consumer protection perspective. Almost alone among nations, only America has a Tom Paine and Federalist Papers/Primary Colors tradition of anonymous or pseudonymic political speech, yet even here — unless the Supreme Court intervenes — short-term passions, politics and national security phobias almost always trump free speech. The old proverb was that “No one knows if you are a dog on the Internet.” Don’t plan on barking much longer!

5. Competition

Competition and antitrust laws will reshape social media providers.

My core training is in antitrust law, although this megatrend has little to do with yours truly. Instead, it stems from the reality that Facebook, Apple and Google, among others, are already facing competition law investigations in the advertising, mobility, search and handset markets. From an economic perspective, there are very strong, positive network effects in social media, far greater than were true in the 1990s for Microsoft’s WIndows OS. As a consequence, viral expansion leads to small social media companies getting VERY big VERY fast: witness Facebook’s 500 million users and Twitter’s phenomenal hockey-stick growth curve. It is difficult for entrepreneurs to shake the old underdog mentality even when their companies become big enough that market power makes their business practices and acquisitions suspect, as Mark Zuckerberg is now learning to his chagrin. And when fueled by financial underwriting from legacy competitors — the dark political underbelly of Washington, DC and Brussels, Belgium antitrust battles — the “nascent” stucture of social media and wireless markets has, to date, not proven sufficient to keep the mitts of antitrusters from the US Department of Justice and the EU’s Competition Directorate from meddling—e.g., Google/Yahoo (2008-09) and Oracle/Sun (2009-10), to name a couple of examples.

6. Location

Location-bsed services will spawn a host of new policy battles.

“Location, location, locations” is not just a real estate slogan, it’s the cross-hairs for a number of policy trends affecting social media. The indicia are not found not just in the geometrically increasing popularity of geo-tagged photos, location check-in apps and games, and the like, but as well and perhaps more importantly in the fact that as wireless communications and data come to dominate telecom — a direct consequence of social networking — regulatory oversight follows almost automatically. “Nomadic” services like VoIP and video chart (e.g., FaceTime), in contrast, present an equally great threat to the established order by making location a matter of indifference. At bottom, this is an industry where eyeballs and advertising dollars still rule. So as marketers devise ever-clever ways to monetize users’ location (including the launch this week of my client shopkick’s location marketing app) all of the bad stuff that can happen online is bound, eventually, to arise with respect to location-based services. LBS isn’t bad; some people are bad. Unfortunately for the FourSquares and Gowallas of the social media world, that has never been enough in most societies to stop gun control—and it won’t be enough to arrest the coming push for consumer protection and marketing regulation in the location services space.

Note: I first used the “megatrends” metaphor while presenting at the 140 Characters Conference-DC (#140onf-dc) in June 2010, and am indebted to organizer Jeff Pulver for serving as my muse for these thoughts. Thanks, Jeff!

It is completely beyond my why the Obama Administration and congressional Democrats could be this obtuse. No one should want — and I doubt any American really does support — the government standardizing serving sizes and recipe compositions, even on health grounds.

Remarkably, Section 4205 of the new health reform law, which requires chain restaurants and vending machines to provide nutrition notices, instructs the HHS Secretary to:

Consider standardization of recipes and methods of preparation, in reasonable variation in serving size and formula of menu items, space on menus and menu boards, inadvertent human error, training of food service workers, variations in ingredients…

HHS Secretary to Regulate Serving Sizes and Recipes for Cheeseburgers and Fries | John Goodman. Who could have known? That’s in part because the provision literally was buried:

You’ve heard the phrase “buried in the bill,” of course. Section 4205 of the “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,” the health care reform bill President Obama signed on March 23, 2010 is contained on pages 1206-14 of a 2407 page bill. It could hardly be more buried than that.

Food Lability Law Blog.

And so, America has gone from “Cheeseburger in Paradise” to “I Can Has Cheeseburger” to self-proclaimed “reformer” rants against Five Guys burgers as Xtreme Eating. What a country! It’s all well and good that Ms. Obama’s pet issue is childhood obesity, but outlawing fatty and big meals will, like illegal drugs, just make them more desirable. So this proposal for more government will inevitably backfire, as well as being totally repulsive from a civil liberties standpoint.

Hearing Room It is hard to understand how “conference reports” from Congress on pending legislation can have fallen from 200 per year to just 11 over the past three decades. Secret Bill Writing On the Rise [Washington Post]. But it indicates, sadly, that laws in America are increasingly being made in back rooms, not the public forums our system of politics has traditionally used. That may be mere window-dressing, but it is IMPORTANT symbolically, in my view.

In a letter to C-SPAN Chairman Brian Lamb, House Republican leader John Boehner wrote, “Unfortunately, the president, Speaker (Nancy) Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader (Harry) Reid now intend to shut out the American people at the most critical hour by skipping a bipartisan conference committee and hammering out a final health care bill in secret.” The complaint sounded a lot like one nine years ago, when Sen. Kent Conrad, D-N.D., said Republicans “locked out the Democrats from the conference committee” meeting on the budget. “We were invited to the first meeting and told we would not be invited back, that the Republican majority was going to write this budget all on their own, which they have done. So much for bipartisanship.”

|

|