A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

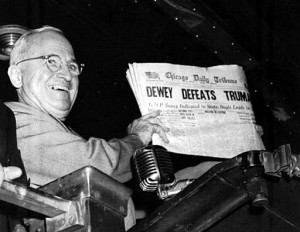

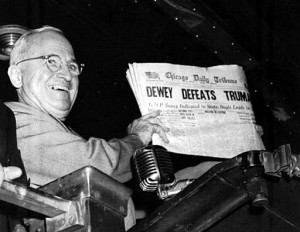

60 years ago, when Harry Truman beat Tom Dewey for the presidency, it was widely predicted by pollsters that Truman would lose. This led to the famous “Dewey Beats Truman” headline in the newspaper proudy flashed by the winning candidate.

The problem, it was later revealed, was that the Gallup organization based its poll results on responses to telephone inquiries. But in the late 1940s, that selection inevitably favored wealthier Republicans, leading to skewed poll results.

Gallup is best known for that one half-century-old blunder. There’s a terrible irony in that. The studious George Gallup did more than anyone to put opinion polling on solid ground.

We have a similar problem today, it appears to me. While telephone subscribership has now become ubiquitous, increasingly many citizens — especially twenty-somethings — no longer use landline telephones, instead going completely wireless. The proportion was 1 in 6 three years ago and continues to increase steadily. Pollsters, however, still base their surveys on landline phone subscribers. In fact, under FCC regulations it is unlawful to telephone a wireless subscriber for a “solicitation” or using an autodialer (a technical prerequisite to modern polling) without either their consent or a prior business relationship. Therefore, despite a non-profit exemption in the FCC’s rules (which, unlike the Federal Trade Commission’s “telemarketing sales rule,” do not expressly exempt political polling), the law is standing in the way of accurate political predictions.

How this will play out in next Tuesday’s elections is unclear to me, as I claim no special expertise in political punditry. But it is revealing that the problems experienced in 1948 are recurring today in a different form due to technological change and the accelerating proliferation of wireless communications devices.

This is the opening paragraph of an article by this author appearing today in the Fall 2010 issue of Icarus, the newsletter of the ABA’s Communications & Digital Technology Industries Committee, Section of Antitrust Law. “If the issue of broadband reclassification is not addressed with sensitivity to the history and traditions of FCC common carrier regulation, one can all too easily arrive at conclusions that simply cannot be squared with the legal framework applied to telecommunications for more than 30 years.”

The highly polarized debate over so-called net neutrality at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) exposes serious philosophical differences about the appropriate role of government in managing technological change. Neither side is unfortunately free either from hyperbole or fear-mongering. And neither side is completely right.

Read the whole essay. It’s provocative.

Note: I have not appeared as counsel for any party to the FCC’s current net neutrality NOI proceeding and was not paid to write this essay (despite what my colleagues and clients in the public interest community may claim). I represented Google in the past but now am ethically precluded from doing so because my law firm has a conflict of interest, being adverse to Google in an employment age discrimination case before the California Supreme Court. The article nonetheless does not reflect the views or opinions of my firm or any of my clients, past or present.

Earlier this week, one month after originally scheduled and following a year of study based on more than 30 requests for public comment — generating some 23,000 comments totaling about 74,000 pages from more than 700 parties — the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) released a 360-page report to Congress on broadband Internet access services. The National Broadband Plan (NBP) encompasses more than 200 recommendations for how Congress, other government agencies and the FCC can improve broadband availability, adoption and utilization, especially for meeting such “national purposes” as economic opportunity, education, energy and the environment, healthcare, government performance, civic engagement and public safety.

Titled Connecting America and praised on its publication by President Obama,1 the NBP presents a wide range of legal, policy, financial and technical proposals, all devoted to meeting the legislative order—first articulated in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA)—of recommending ways to make broadband ubiquitous for Americans. Much of the general outlines and major recommendations of the plan were revealed in a series of public appearances and media briefings by FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski over the past several weeks. Only the NBP’s executive summary was made available before the full plan’s official March 16 publication. The public release of the entire document reveals the whole plan, including details on the recommendations as well as the reasoning behind them and the FCC’s goals.

The ambitious NBP sets as a national goal the delivery to all Americans of 100 megabits per second (Mbps) Internet service within 10 years, informally known as the “10 squared” objective. Its premise is that “[l]ike electricity a century ago, broadband is a foundation for economic growth, job creation, global competitiveness and a better way of life.”2 The policies and actions recommended in the plan fall into three major categories: fostering innovation and competition in networks, devices and applications; redirecting assets that government controls or influences in order to spur investment and “inclusion”; and optimizing the use of broadband to help achieve national priorities.

The FCC’s plan addresses wide range of interrelated issues, such as intercarrier compensation, universal service reform, spectrum reallocation (making 500 megahertz of spectrum newly available for broadband within 10 years), digital literacy, E-Rate (Schools and Libraries Program of the Universal Service Fund) services, set-top-box unbundling, affordability, “smart grid” electrical services, telemedicine, state and municipal broadband networks, distance education, wireless data services, homeland security and first-responder communications, wireless connectivity to digital-learning devices, Internet anonymity and privacy, data-center energy efficiency, video “gateway” network interface devices, and use of unlicensed spectrum (such as WiFi). The plan includes a proposal for the federal government to repurpose $15.5 billion in existing telecom-industry subsidies away from traditional landline telephone services to broadband, concluding that—

If Congress wishes to accelerate the deployment of broadband to unserved areas and otherwise smooth the transition of the [Universal Service] Fund, it could make available public funds of a few billion dollars per year over two to three years.3

Release of the NBP marks the start of what is likely to be a long and hotly debated implementation process, as the plan pits the interests of different industry segments against one other and tests the limits of the FCC’s regulatory authority.4 While lauding the plan’s aspirations, some critics in the first days after its release include broadcast television stations that are being asked to “voluntarily” relinquish valuable digital spectrum, satellite and cable companies that object to further regulation of their so-called navigation devices and rural telephone providers that are concerned with the potential loss of substantial Universal Service Fund (USF) revenues. Information technology (IT) and content delivery networks (CDNs) also have expressed concern that the FCC’s related net neutrality initiative would circumscribe their ability to offer quality of service (QoS) and packet-prioritized media services. Free-market advocates (both think tank and government) as well as Republican FCC Commissioner Robert McDowell have already declared that the plan is unnecessary or at least unnecessarily regulatory.5

Connecting America details a series of economic and public policy goals for the United States, which according to some studies has fallen in penetration and “adoption” of broadband Internet services from first in the world in the late 1990s to somewhere between 15th place to 20th place as of 2008.6 These goals are highlighted below.

- At least 100 million U.S. homes should have affordable access to actual download speeds of at least 100 Mbps and actual upload speeds of at least 50 Mbps.

- The United States should lead the world in mobile innovation, with the fastest and most extensive wireless networks of any nation.

- All Americans should have affordable access to robust broadband service, and the means and skills to subscribe if they so choose.

- Every American community should have affordable access to at least 1 gigabit per second broadband service to anchor institutions, such as schools, hospitals and government buildings.

- To ensure the safety of the American people, every first-responder should have access to a nationwide, wireless, interoperable broadband public-safety network.

- To ensure that America leads in the clean-energy economy, all Americans should be able to use broadband to track and manage their real-time energy consumption.

All of these goals are supported by proposals for the federal government to become more deeply involved in collecting and assessing statistical metrics on the availability, speed and use of broadband services and that the FCC impose “performance disclosure requirements” and “performance standards” on broadband service providers, including wireless and cellular carriers.7 As the trade publication Telecommunications Reports notes:

This recommendation illustrates how the plan could bump up against independent congressional initiatives. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D.-Minn.) introduced a broadband performance management bill along similar lines that directed an FCC rulemaking action, rather than NIST standards, and which mandated industry use of the terms as the FCC defines them.8

In some of its more controversial recommendations, the NBP proposes that broadband success be measured not only by the statutory objective of “access to broadband capability,”9 but also by adoption percentages and affordability, using a national commitment to “inclusiveness” as the principal justification. “While it is important to respect the choices of those who prefer not to be connected, the different levels of adoption across demographic groups suggest that other factors influence the decision not to adopt. Hardware and service are too expensive for some. Others lack the skills to use broadband.”10 The FCC also proposes creation of a Digital Literacy Corps, modeled after President John F. Kennedy’s Peace Corps initiative, to educate minority and disadvantaged citizens on the use and importance of computers and Internet services. Having successfully subsidized the connection of more than 95 percent of America’s classrooms to the Internet, the FCC’s plan further recommends that the E-Rate program be expanded to cover off-campus network use, e-readers and a variety of even newer functions. Among the recommendations for congressional action, the highest price tag—up to $16 billion—would be for grants to cover capital and operational costs of an interoperable public-safety mobile broadband network. As was revealed previously, the NBP also proposes auctioning the 700-megahertz “D block” rather than allocating it to public safety and first-responder services.

There are likely to be numerous FCC notice-and-comment rulemakings, legislative hearings and policy workshops initiated over the next 12 to 18 months to implement the NBP. As Connecting America emphasizes in its executive summary:

Public comment on the plan does not end here. The record will guide the path forward through the rulemaking process at the FCC, in Congress and across the Executive Branch, as all consider how best to implement the plan’s recommendations. The public will continue to have opportunities to provide further input all along this path.

The FCC has stated it will publish a timetable of actions in the near future and is anticipated to begin what may be considered more challenging NPRM proceedings, such as USF reform, within 60 to 90 days. Whether in the IT, telecom, energy or healthcare industries, companies involved in a wide range of different markets are likely to be affected by the National Broadband Plan for years to come and should consider participating in the rulemaking and parallel legislative processes.

**[This is a client alert I prepared for my law firm, Duane Morris LLP, which holds the copyright. The alert is available here.]

Footnotes

- “President Obama Hails Broadband Plan,” Washington Post, March 16, 2010.

- Connecting America at xiv, 9.

- Connecting America at xiii.

- See, e.g., “FCC Chairman Genachowski Confident in Authority over Broadband, Despite Critics,” Washington Post, March 3, 2010.

- “FCC’s National Broadband Plan Raises Divisive Issues,” USA Today, March 17, 2010. Compare B. Reed, “Who Else Wants National Broadband?”, Business Week, March 16, 2010, with J. Chambers, “Why America Needs a National Broadband Plan,” Business Week, March 16, 2010.

- Connecting America at xiv.

- Connecting America at 35–36. “The FCC and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) should collect more detailed and accurate data on actual availability, penetration, prices, churn and bundles offered by broadband service providers to consumers and businesses, and should publish analyses of these data.” Id. at 35.

- T.R. Daily, March 15, 2010, at 2.

- ARRA § 6001(k)(2)(D), 123 Stat. 115, 516 (2009).

- Connecting America at 23.

Another great title (and incisive post) from my friend and client Drew Clark at BroadbandCensus.com. I suppose the reaction in Silicon Valley to folks saying they’re from Washington, DC and are “here to help” may just be slightly more favorable going-forward. FCC Chairman Kein Martin’s Incredible Silicon Valley Wi-Fi Adventure. Well done!

That’s what Andrew Orlowski of the UK’s The Register calls Friday’s decision by the Federal Communications Commission to cite Comcast for unlawful violation of "network neutrality" principles. One can agree or disagree with the proposition, endorsed by FCC Chairman Kevin Martin, that Internet users should be free to reach any site without interference by their ISPs.

“We are preserving the open character of the Internet,” Martin said in an interview after the 3-to-2 vote. “We are saying that network operators can’t block people from getting access to any content and any applications.”

But it is just absurd to conclude that any federal government agency should be allowed to issue what it expressly terms a set of non-binding "principles" and then make an official finding of illegality when a company fails to follow those principles. Confusing is an understatement here. Dissenting Commissioner Rob McDowell’s complaint that the FCC here is actively regulating the Internet — or at least historically unregulated "enhanced services" offered by ISPs, unlike common carrier telecommunications services — is spot on.

|

|