A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

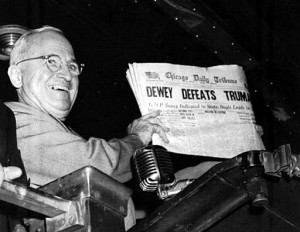

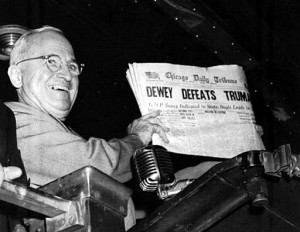

60 years ago, when Harry Truman beat Tom Dewey for the presidency, it was widely predicted by pollsters that Truman would lose. This led to the famous “Dewey Beats Truman” headline in the newspaper proudy flashed by the winning candidate.

The problem, it was later revealed, was that the Gallup organization based its poll results on responses to telephone inquiries. But in the late 1940s, that selection inevitably favored wealthier Republicans, leading to skewed poll results.

Gallup is best known for that one half-century-old blunder. There’s a terrible irony in that. The studious George Gallup did more than anyone to put opinion polling on solid ground.

We have a similar problem today, it appears to me. While telephone subscribership has now become ubiquitous, increasingly many citizens — especially twenty-somethings — no longer use landline telephones, instead going completely wireless. The proportion was 1 in 6 three years ago and continues to increase steadily. Pollsters, however, still base their surveys on landline phone subscribers. In fact, under FCC regulations it is unlawful to telephone a wireless subscriber for a “solicitation” or using an autodialer (a technical prerequisite to modern polling) without either their consent or a prior business relationship. Therefore, despite a non-profit exemption in the FCC’s rules (which, unlike the Federal Trade Commission’s “telemarketing sales rule,” do not expressly exempt political polling), the law is standing in the way of accurate political predictions.

How this will play out in next Tuesday’s elections is unclear to me, as I claim no special expertise in political punditry. But it is revealing that the problems experienced in 1948 are recurring today in a different form due to technological change and the accelerating proliferation of wireless communications devices.

I’ve posted a set of legible slides from my SocialStrat presentation on managing enterprise legal risks in social media. Find them here in native format or on the LexDigerati presentations page.

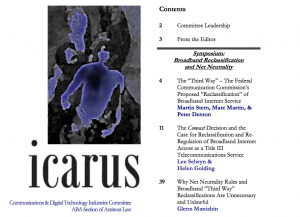

This is the opening paragraph of an article by this author appearing today in the Fall 2010 issue of Icarus, the newsletter of the ABA’s Communications & Digital Technology Industries Committee, Section of Antitrust Law. “If the issue of broadband reclassification is not addressed with sensitivity to the history and traditions of FCC common carrier regulation, one can all too easily arrive at conclusions that simply cannot be squared with the legal framework applied to telecommunications for more than 30 years.”

The highly polarized debate over so-called net neutrality at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) exposes serious philosophical differences about the appropriate role of government in managing technological change. Neither side is unfortunately free either from hyperbole or fear-mongering. And neither side is completely right.

Read the whole essay. It’s provocative.

Note: I have not appeared as counsel for any party to the FCC’s current net neutrality NOI proceeding and was not paid to write this essay (despite what my colleagues and clients in the public interest community may claim). I represented Google in the past but now am ethically precluded from doing so because my law firm has a conflict of interest, being adverse to Google in an employment age discrimination case before the California Supreme Court. The article nonetheless does not reflect the views or opinions of my firm or any of my clients, past or present.

This is the SlideShare copy of my webinar presentation this afternoon for the SociaLex conference, focusing on the legal issues arising in connection with social media and managing socmedia legal risks in the enterprise. Slide quality is not the best, so I’ll repost later in native format. [The native format slides are here.]

Several of the previous posts in my The Law of Social Media essay series focus on core legal issues, such as copyright in user-generated content and employer use of social media for HR decisions. This one is a bit different. Like John Naisbitt, it describes what I am convinced are the most significant law/policy “megatrends” affecting the social media space today.

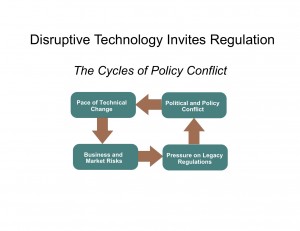

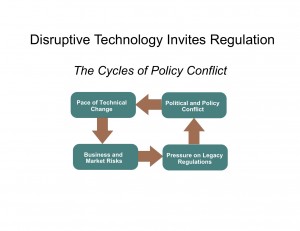

As an overview, consider the following scenario—and click for a larger image:

As the graphic indicates, the reality is that disruptive technologies quickly and visibly invite governmental regulation. That’s because change creates business and policy risks, which threaten legacy products and powerful business incumbents, and in turn which cause political pressures to protect established constituencies. Since social media is most assuredly a disruptive force, this circular pattern will likely manifest itself — in fact, as I discuss below it already has — in public policies towards social media and social networking communications.

1. Censorship & Filtering

Governments absolutely hate “unfiltered” social media and will move to censor and control it.

In the East, the basis for such censorship is political and religious oppression, as in Iran, North Korea, China, etc. In the West, the more unlikely culprit has been intellectual property (e.g., music and movie copyrights) and obscenity, as in Australia, France and New Zealand’s efforts to install country-wide porn filters and institute a “the strikes” rule against P2P file sharing. And everywhere, government mourns the loss of the historic financial and advertising basis for traditional media like newspapers and broadcast television, proposing to bail out or subsidize the latter in order to prevent social media from achieving dominance at the expense of last century’s communications technologies. Censorship is far from dead on the Web; in fact, it’s really only beginning.

2. Privacy

The EU’s strict data protection (privacy) regime will spread and overtake the US opt-out approach.

Most everyone knows that the European Union has a highly protective scheme of individual privacy in the digital age. Fewer understand that in the United States, with the exception of specially regulated industries like health care and financial services, the only privacy protections available are basically those the Constitution provides as against the government. That will change, however. The EU is too large a market for businesses to overlook, commerce today is fully globalized and while the United States remains the least privacy-centric of any major industrialized nation, that is changing as legislators and regulators more often choose an opt-in requirement for newer, albeit still infrequent, electronic privacy measures.

3. Criminal Law

Cyber offenses will (finally) be created.

In the past, criminal violations involving the Internet and online activities have largely focused on corporate interests, like the Anti-Cybersquatting, CFAA and CAN-SPAM Acts. But the current proliferation of pedophilia, cyber-bullling, stalking and other socially offensive digital-centric conduct is different. Many times, existing criminal laws — for instance, of assault — are not broad enough to cover online conduct. Other time, prosecutors are reluctant to indict and juries even more reluctant to convict. Yet the US congressional approach to indecency on the Web has for more than a decade been to attempt to ban conduct deemed seedy, whether pornography or gambling, to avoid having the “new” media infected with perceived old evils, for instance the Communications Decency Act of 1996. As a result, there is a good chance, well above 50% in my estimation, that the next several years will bring a proliferation of state and federal laws making criminally unlawful specific forms of online activity deemed socially deviant or harmful.

4. Anonymity

Anonymity on the Internet is under assault and may be lost.

A timely prediction, given that just yesterday two different courts compelled the unmasking of anonymous commenters in civil pretrial discovery—when the posters were not even parties to the cases. Ninth Circuit Upholds Unmasking of Online Anonymous Speakers and Illinois Appellate Court Unmasks Anonymous Commenters. There are a variety of reasons, but the principal one is that by defeating anonymity, politicians can be seen as “protecting” the victims of Web-based schemes, involving both antisocial (i.e., bullying, extortion, etc.) and anti-consumer (i.e., stock pump-and-dump chats, etc.) behavior, which sometimes end quite tragically, as in teenage suicides. This is reinforced by the continuing efforts of copyright holders (music, photos, video, news) to require ISPs to disgorge the identities of infringing users and by the FTC’s sponsored blogging “guidelines,” which support the theme of transparency from a consumer protection perspective. Almost alone among nations, only America has a Tom Paine and Federalist Papers/Primary Colors tradition of anonymous or pseudonymic political speech, yet even here — unless the Supreme Court intervenes — short-term passions, politics and national security phobias almost always trump free speech. The old proverb was that “No one knows if you are a dog on the Internet.” Don’t plan on barking much longer!

5. Competition

Competition and antitrust laws will reshape social media providers.

My core training is in antitrust law, although this megatrend has little to do with yours truly. Instead, it stems from the reality that Facebook, Apple and Google, among others, are already facing competition law investigations in the advertising, mobility, search and handset markets. From an economic perspective, there are very strong, positive network effects in social media, far greater than were true in the 1990s for Microsoft’s WIndows OS. As a consequence, viral expansion leads to small social media companies getting VERY big VERY fast: witness Facebook’s 500 million users and Twitter’s phenomenal hockey-stick growth curve. It is difficult for entrepreneurs to shake the old underdog mentality even when their companies become big enough that market power makes their business practices and acquisitions suspect, as Mark Zuckerberg is now learning to his chagrin. And when fueled by financial underwriting from legacy competitors — the dark political underbelly of Washington, DC and Brussels, Belgium antitrust battles — the “nascent” stucture of social media and wireless markets has, to date, not proven sufficient to keep the mitts of antitrusters from the US Department of Justice and the EU’s Competition Directorate from meddling—e.g., Google/Yahoo (2008-09) and Oracle/Sun (2009-10), to name a couple of examples.

6. Location

Location-bsed services will spawn a host of new policy battles.

“Location, location, locations” is not just a real estate slogan, it’s the cross-hairs for a number of policy trends affecting social media. The indicia are not found not just in the geometrically increasing popularity of geo-tagged photos, location check-in apps and games, and the like, but as well and perhaps more importantly in the fact that as wireless communications and data come to dominate telecom — a direct consequence of social networking — regulatory oversight follows almost automatically. “Nomadic” services like VoIP and video chart (e.g., FaceTime), in contrast, present an equally great threat to the established order by making location a matter of indifference. At bottom, this is an industry where eyeballs and advertising dollars still rule. So as marketers devise ever-clever ways to monetize users’ location (including the launch this week of my client shopkick’s location marketing app) all of the bad stuff that can happen online is bound, eventually, to arise with respect to location-based services. LBS isn’t bad; some people are bad. Unfortunately for the FourSquares and Gowallas of the social media world, that has never been enough in most societies to stop gun control—and it won’t be enough to arrest the coming push for consumer protection and marketing regulation in the location services space.

Note: I first used the “megatrends” metaphor while presenting at the 140 Characters Conference-DC (#140onf-dc) in June 2010, and am indebted to organizer Jeff Pulver for serving as my muse for these thoughts. Thanks, Jeff!

This is an ongoing issue with the American judiciary system. Judges are by institution isolated and by tradition older than the general population. Increasingly, however, they are called upon to rule on technologies with which they have no experience at all.

It does’t look like we’ll be seeing much Tweeting-from-the-bench on the Supreme Court any time soon, but the Hillicon Valley blog highlights an amusing moment at a recent House Judiciary subcommittee meeting, attended by two Supreme Court Justices — Antonin Scalia and Stephen Breyer in which they’re asked if they plan on using Twitter any time soon. Scalia says he doesn’t even know anything about it — and notes that his wife refers to him as “Mr. Clueless.” Reassuring to know that of a Supreme Court Justice. Breyer, however, seems to indicate a realization that Twitter, as a communication platform, really could be quite powerful.

Subcommittee Chair Steve Cohen: Have either of y’all ever consider tweeting or twitting?

Justice Scalia: I don’t even know what it is. To tell you the truth, I have heard it talked about. But, you know, my wife calls me Mr. Clueless — I don’t know about tweeting.

Justice Breyer: Well, I have no personal experience with that. I don’t even know how it works. But, remember when we had that disturbance in Iran? My son said, ‘Go look at this.’ And oh, my goodness. I mean, there were some Twitters, I called them, there were people there with photographs as it went on. And I sat there for two hours absolutely hypnotized. And I thought, ‘My goodness, this is now, for better or for worse, I think maybe for many respects for better, in that instance certainly, it’s not the same world. It’s instant and people react instantly… and there we are. It’s quite a difference there and it’s not something that’s going to go away.

Posted via web from glenn’s posterous

I’m not sure I am altogether comfortable with this technology, yet.

Posted via web from glenn’s posterous

In a decision that has already generated a huge volume of commentary and predictions,1/ just three days ago the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit reversed a contentious ruling by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) from 2008 that penalized Comcast Corp. for violating the Commission’s “network neutrality” Internet principles. Comcast Corp. v. FCC, No. 08-1291 (D.C. Cir. April 6, 2010). Those principles include a content access requirement that the FCC said prohibited broadband operators and other Internet Service Providers (ISPs) from using network management practices to block or “throttle” specific Internet Protocol (IP) based services, such as the peer-to-peer, or P2P, filing-sharing communications offered by BitTorrent.

The Court’s opinion represents a devastating blow to the FCC’s assertion of ancillary jurisdiction authority over the Internet, ISPs and IP-based services. It calls into question how, if at all, the agency can implement many of the proposals put forward in its recent National Broadband Plan (NBP) and the “open Internet” proceeding launched last fall to codify those 2005 net neutrality principles (plus two additional rules proposed by new FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski). And the D.C. Circuit decision calls out for resolution by Congress of the jurisdictional void created — a call some legislators have already heeded.2/

Yet much of this crisis mentality appears unwarranted. There are accepted legal bases the FCC could employ to achieve a substantial part of its objectives related to consumer protection on the Internet. Where the FCC may not by statute operate, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) — which for several years has been biting at the bit to oversee broadband competition and consumer protection — can. That is because the Comcast decision compels the conclusion, at the very least, that broadband is not a “common carrier” service over which the FCC enjoys exclusive federal jurisdiction. The FCC’s proposal in its recent broadband plan that the agency apply universal service funds to subsidize broadband deployment in rural areas is likely not threatened materially by the Comcast decision. And the larger public policy fight over so-called “reclassification” of broadband as a Title II service presupposes, incorrectly, that Title II treatment means subjecting IP-based services to the same, traditional public utility model of regulation as monopoly telephone providers. In short, the agency and Congress face a dizzying array of alternatives and options. Yet much of this crisis mentality appears unwarranted. There are accepted legal bases the FCC could employ to achieve a substantial part of its objectives related to consumer protection on the Internet. Where the FCC may not by statute operate, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) — which for several years has been biting at the bit to oversee broadband competition and consumer protection — can. That is because the Comcast decision compels the conclusion, at the very least, that broadband is not a “common carrier” service over which the FCC enjoys exclusive federal jurisdiction. The FCC’s proposal in its recent broadband plan that the agency apply universal service funds to subsidize broadband deployment in rural areas is likely not threatened materially by the Comcast decision. And the larger public policy fight over so-called “reclassification” of broadband as a Title II service presupposes, incorrectly, that Title II treatment means subjecting IP-based services to the same, traditional public utility model of regulation as monopoly telephone providers. In short, the agency and Congress face a dizzying array of alternatives and options.

This post has two parts:

- First, I review the proceedings leading up to and the substance of Circuit Judge David S. Tatel’s opinion for a unanimous three-judge panel of the court of appeals.

- Second, I put the decision into context and explore ways in which the FCC could react, including the legal rationale(s) the agency would need to develop on remand.

Both portions of the essay, however, are of necessity general overviews. A complete examination of this rather wonk-ish area of communications jurisprudence requires a longer treatise than warranted for such a time-sensitive post. I encourage readers to address these issues in greater detail in comments below and to the FCC in its open Internet NPRM proceeding.

1. The Comcast Decision

The FCC had classified cable modem service as an information service under the bifurcated regulatory approach of Computer II and the 1996 Telecommunications Act, a ruling affirmed by the by the Supreme Court in NCTA v. Brand X, 545 U.S. 967 (2005). Nonetheless, the Commission later developed a set of four network neutrality principles adopted in a 2005 “policy statement.” These were intended to protect what the agency perceived as a threat to the open character of the Internet if vertically integrated content providers blocked or discriminated against other Web sites and content in order to favor their own IP-based services.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

Much like the assumptions underlying the NBP, the net neutrality principles aspired to an Internet free of any provider’s control, giving every end user access — with little or no permissible differentiation among services or even packets — to all content available anywhere, anytime. (They also harkened to a similar failed effort by public interest advocates, in the late 1990s, for what was then termed “cable open access.”)

Whether or not regulatory intervention is needed to ensure this result was not at issue in the Comcast appeal, but it was central to the FCC’s enforcement action that triggered the case. Faced with the reality that file-sharing end users were consuming huge amounts of bandwidth, Comcast deliberately limited their ability to use P2P client-side applications by first outright blocking, and later imposing network management controls on, BitTorrent IP traffic, so that the latency-sensitive applications of the majority of its Internet customers would be delivered uninterrupted. Some consumer advocates alleged that the cable giant did so in order to protect its own on-demand video programming services from potential competition. Comcast stopped the practice after the story came out but was later discovered to have misled the Commission with its initial responses, and the company never revealed to customers that some IP traffic was not being routed with the same throughput as other services. The FCC subsequently imposed reporting and disclosure requirements on Comcast’s traffic management practices, based on the 2005 policy statement, which the agency had not promulgated as actual rules or regulations.

Comcast appealed that decision. The FCC defended its actions on the ground that, even though Internet broadband is not a telecommunications service subject to Title II of the Act, the agency has ancillary jurisdiction to regulate. That ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, sometimes confusingly referred to as “Title I jurisdiction,” is based on a 1960s-era decision by the Supreme Court in which the FCC had restricted cable television by regulation in order to protect traditional TV broadcasters, over which the agency enjoyed express statutory authority. In Comcast, the D.C. Circuit concluded that under that approach, ancillary regulations must be ancillary to something explicit in the Act, in other words that the Commission must show that its traffic management directive was “reasonably ancillary to the … effective performance of its statutorily mandated responsibilities.” Finding that the FCC had not done so, the Court reversed.

Without detailing each of the statutory hooks advanced by the Commission, it suffices to say that the agency did not seriously urge the court of appeals to sustain ancillary Internet regulation in order to protect its Title II, III (broadcasting) or VI (cable) jurisdiction over legacy services for which the Communications Act grants explicit regulatory authority. Instead the FCC urged that various general statements of public policy appearing in the 1996 Act amendments provided the necessary linkage. The D.C. Circuit rejected that contention, concluding that policy does not suffice under the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine as a statutorily mandated responsibility. The FCC also cited section 706 of the 1996 Act, which directs it to “encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans.” The Court likewise rejected that linkage because the Commission itself had long ago ruled that section 706 does not constitute “an independent grant of authority” to the agency.

These holdings, foreshadowed earlier by oral argument — see “Appeals Court Unfriendly To FCC’s Internet Slap At Comcast” [Wall Street Journal] — are relatively unsurprising. What is somewhat unusual is that, in its appellate positions, the FCC suggested additional grounds for an ancillary jurisdiction theory that had not been relied on in its 2008 order. The most cogent of these added rationales was that Internet openness and nondiscrimination is ancillary to the “just and reasonable practices” mandate of sections 201(b) and 202(a), applicable to telecom carriers. Judge Tatel’s opinion dismissed these post-hoc justifications not on the substance, but rather because Administrative Procedure Act precedent requires a reviewing federal court to sustain or reverse a regulatory order on the same grounds offered by the agency in its underlying decision.

Comcast’s challenge of the 2008 order had offered the Court the opportunity to overturn it on the narrower ground that principles, unlike rules, are not enforceable in company-specific adjudications. But the D.C. Circuit did not reach that question. Its analysis essentially concurred with dissenting Commissioner Robert McDowell’s criticism that “[u]nder the analysis set forth in the order, the FCC apparently can do anything so long as it frames its actions in terms of promoting the Internet or broadband deployment.”3/

The end result is that the FCC’s network neutrality principles are effectively dead, for now at least. The agency has various options available, but unless and until it develops either an alternative rationale under its existing statutory framework, or procures a new legislative grant of authority from Congress, it cannot police the practices of ISPs and broadband providers. It is to these alternatives and their viability that I now turn.

2. The Post-Comcast Regulatory & Legislative Environment

In the wake of the D.C. Circuit’s decision, network neutrality advocates urged the FCC to ensure Internet openness by “reclassifying” broadband as Title II telecom service. Gloating opponents opined that the FCC was properly chastised and should rein in its efforts to regulate what they view as an increasingly competitive market, in which most major ISPs have long ago pledged to respect net openness as a business matter. Meanwhile, Web-based grassroots campaigns, with typical rhetorical excesses, sprang up overnight to “save Internet freedom.”

The reality is somewhere in between. Had the FCC desired, it could have — and still might — justify its ancillary jurisdiction by articulating a relationship between broadband Internet access and traditional, regulated communications services. By declining to review the Obama Commission’s arguments based on the mandatory obligations of reasonable rates and practices under Title II, the court of appeals has all but begged the FCC to do so on remand. The problem with this approach, especially given the history of the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, is that it reflects a paternalistic, corporate welfare model of economic regulation which is out of favor as a policy matter with politicians, regardless of their party affiliation or ideology.

It would not, however, require much in the way of legislation to give the FCC explicit authority to adopt and impose network neutrality nondiscrimination rules. In its 2009 stimulus legislation, Congress allocated $7.2 billion for distribution by executive branch agencies in the form of grants to spur broadband deployment. A portion of those funds was expressly conditioned on grantees’ agreement in advance to comply with the Commission’s 2005 network neutrality principles. Unlike broader calls to completely rewrite the Communications Act in light of convergence, a legislative “fix” specific to net neutrality would not be unusually difficult. Whether there exists the political will and votes to do so, especially in the aftermath of the divisive healthcare reform debate, is unclear.

Nor does the Comcast decision by the D.C. Circuit necessarily spell the death knell for the Commission’s National Broadband Plan. Some of its proposals, such as privacy protections for broadband end users and truth-in-billing disclosure requirements for ISPs, would surely require new legislative authority. Yet the basic objectives of the plan, including its proposal to allocate an additional $16 billion in universal service funds to subsidize broadband services, are not necessarily invalid after Comcast. That is because section 254 of the Act likely allows the FCC to both collect USF contributions from and — as reflected in the E-rate program — use them for “advanced services” like Internet access. Nor does the Comcast decision by the D.C. Circuit necessarily spell the death knell for the Commission’s National Broadband Plan. Some of its proposals, such as privacy protections for broadband end users and truth-in-billing disclosure requirements for ISPs, would surely require new legislative authority. Yet the basic objectives of the plan, including its proposal to allocate an additional $16 billion in universal service funds to subsidize broadband services, are not necessarily invalid after Comcast. That is because section 254 of the Act likely allows the FCC to both collect USF contributions from and — as reflected in the E-rate program — use them for “advanced services” like Internet access.

The final FCC option is to reconsider its earlier rulings that Internet access services (at least when integrated with IP transport) are “information services” for purposes of the 1996 Act’s classifications. Some analytical jujitsu would obviously be required to achieve that result, since the agency needs to develop and articulate changed circumstances that rationally justify a reversal of its prior ruling. But since the Supreme Court has recently emphasized that the APA does not impose on administrative agencies any higher burden of justification to repeal or revise its rules and policies than to adopt them in the first place, the FCC conceivably might be able to satisfy that standard.

Much of the opposition to this sort of “reclassification” stems from the fear that characterizing Internet access as a telecommunications service would carry with it the full panoply of legacy Title II dominant carrier regulation, such as rate-of-return pricing, entry and exit licensing and the like. The two, however, are not co-extensive. It has been the law for several decades, codified by Congress in 1996, that the FCC enjoys the ability to refrain or “forbear” from regulation. Reclassifying broadband as a Title II telecom service could, at least hypothetically, be coupled with a simultaneous decision forbearing from application of most substantive regulations to ISPs.4/ Yet at least to public interest advocates, that would be viewed as a loss; in their regulatory paradigm broadband represents the new common carriage and should be offered on a quasi-utility basis. That perception will need to be changed if proponents of reclassification are to stand a realistic chance of persuading the agency and, more importantly, successfully withstanding judicial review.

Finally, under both the Bush and Obama Administrations the FTC has expressed a clear desire to exercise its own statutory jurisdiction over broadband services. Historically, the FTC is precluded from applying the Federal Trade Commission Act and its unfair competition and consumer protection standards to common carriers. But absent reclassification, broadband is plainly not a common carrier service under either the Communications Act or the FTC Act. As a result, although FTC Chairman John Liebowitz has not made a public statement to date in the wake of Comcast, most observers expect that agency to move relatively rapidly into broadband for purposes of filling the void left in the wake of the court of appeals’ decision.

Conclusion

Network neutrality is a complex, contentious and confusing issue. While the D.C. Circuit’s opinion is abundantly clear, it is not apparent how the FCC or Congress will respond and whether the agency will seek Supreme Court certiorari review to test the basis and scope of its ancillary jurisdiction. Having persisted formally since 2005, and as a matter of policy debate for more than a decade, net neutrality is not necessarily dead, it is just entering a new phase of consciousness. That it looks comatose is perhaps a mirage that will be evaporated with time.

Footnotes

1/ Court Limits FCC Power Over Internet,” Boston Globe, April 7, 2010; Editorial, “FCC Must Quickly Reclaim Authority Over Broadband,” San Jose Mercury News, April 7, 2010; “FCC to Start Writing Internet Rules After U.S. Court Setback,” Business Week, April 8, 2010.

2/ Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), chair of the House Committee on Energy & Commerce, announced almost immediately that he is “working with the Commission, industry, and public interest groups to ensure that the Commission has appropriate legal authority to protect consumers.” Waxman Statement, April 6, 2010. Earlier, in July 2009, Reps. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) and Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.) introduced H.R. 3458, the Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2009, to enshrine what the legislation terms “Internet freedom” into law. However, In 2006 Congress failed to pass five bills, backed by groups including Google, Amazon.com, Free Press and Public Knowledge, that would have handed the FCC the power to oversee network neutrality compliance.

3/ See also R. McDowell, “Hands Off the Internet,” Washington Post, April 8, 2010.

4/ In response to concerns voiced regarding reclassification, Rep. Markey said that even under Title II, the FCC could forbear if it wanted to” and that in the past it had “availed itself” of that power. “We shouldn’t pretend that going back to Title II would mean that the earth would stop spinning on its axis and it would be the end of times,” he added. See “Concerns About Title II Reclassification Aired at House Hearing on Broadband Plan,” T.R. Daily, April 8, 2010.

Earlier this week, one month after originally scheduled and following a year of study based on more than 30 requests for public comment — generating some 23,000 comments totaling about 74,000 pages from more than 700 parties — the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) released a 360-page report to Congress on broadband Internet access services. The National Broadband Plan (NBP) encompasses more than 200 recommendations for how Congress, other government agencies and the FCC can improve broadband availability, adoption and utilization, especially for meeting such “national purposes” as economic opportunity, education, energy and the environment, healthcare, government performance, civic engagement and public safety.

Titled Connecting America and praised on its publication by President Obama,1 the NBP presents a wide range of legal, policy, financial and technical proposals, all devoted to meeting the legislative order—first articulated in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA)—of recommending ways to make broadband ubiquitous for Americans. Much of the general outlines and major recommendations of the plan were revealed in a series of public appearances and media briefings by FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski over the past several weeks. Only the NBP’s executive summary was made available before the full plan’s official March 16 publication. The public release of the entire document reveals the whole plan, including details on the recommendations as well as the reasoning behind them and the FCC’s goals.

The ambitious NBP sets as a national goal the delivery to all Americans of 100 megabits per second (Mbps) Internet service within 10 years, informally known as the “10 squared” objective. Its premise is that “[l]ike electricity a century ago, broadband is a foundation for economic growth, job creation, global competitiveness and a better way of life.”2 The policies and actions recommended in the plan fall into three major categories: fostering innovation and competition in networks, devices and applications; redirecting assets that government controls or influences in order to spur investment and “inclusion”; and optimizing the use of broadband to help achieve national priorities.

The FCC’s plan addresses wide range of interrelated issues, such as intercarrier compensation, universal service reform, spectrum reallocation (making 500 megahertz of spectrum newly available for broadband within 10 years), digital literacy, E-Rate (Schools and Libraries Program of the Universal Service Fund) services, set-top-box unbundling, affordability, “smart grid” electrical services, telemedicine, state and municipal broadband networks, distance education, wireless data services, homeland security and first-responder communications, wireless connectivity to digital-learning devices, Internet anonymity and privacy, data-center energy efficiency, video “gateway” network interface devices, and use of unlicensed spectrum (such as WiFi). The plan includes a proposal for the federal government to repurpose $15.5 billion in existing telecom-industry subsidies away from traditional landline telephone services to broadband, concluding that—

If Congress wishes to accelerate the deployment of broadband to unserved areas and otherwise smooth the transition of the [Universal Service] Fund, it could make available public funds of a few billion dollars per year over two to three years.3

Release of the NBP marks the start of what is likely to be a long and hotly debated implementation process, as the plan pits the interests of different industry segments against one other and tests the limits of the FCC’s regulatory authority.4 While lauding the plan’s aspirations, some critics in the first days after its release include broadcast television stations that are being asked to “voluntarily” relinquish valuable digital spectrum, satellite and cable companies that object to further regulation of their so-called navigation devices and rural telephone providers that are concerned with the potential loss of substantial Universal Service Fund (USF) revenues. Information technology (IT) and content delivery networks (CDNs) also have expressed concern that the FCC’s related net neutrality initiative would circumscribe their ability to offer quality of service (QoS) and packet-prioritized media services. Free-market advocates (both think tank and government) as well as Republican FCC Commissioner Robert McDowell have already declared that the plan is unnecessary or at least unnecessarily regulatory.5

Connecting America details a series of economic and public policy goals for the United States, which according to some studies has fallen in penetration and “adoption” of broadband Internet services from first in the world in the late 1990s to somewhere between 15th place to 20th place as of 2008.6 These goals are highlighted below.

- At least 100 million U.S. homes should have affordable access to actual download speeds of at least 100 Mbps and actual upload speeds of at least 50 Mbps.

- The United States should lead the world in mobile innovation, with the fastest and most extensive wireless networks of any nation.

- All Americans should have affordable access to robust broadband service, and the means and skills to subscribe if they so choose.

- Every American community should have affordable access to at least 1 gigabit per second broadband service to anchor institutions, such as schools, hospitals and government buildings.

- To ensure the safety of the American people, every first-responder should have access to a nationwide, wireless, interoperable broadband public-safety network.

- To ensure that America leads in the clean-energy economy, all Americans should be able to use broadband to track and manage their real-time energy consumption.

All of these goals are supported by proposals for the federal government to become more deeply involved in collecting and assessing statistical metrics on the availability, speed and use of broadband services and that the FCC impose “performance disclosure requirements” and “performance standards” on broadband service providers, including wireless and cellular carriers.7 As the trade publication Telecommunications Reports notes:

This recommendation illustrates how the plan could bump up against independent congressional initiatives. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D.-Minn.) introduced a broadband performance management bill along similar lines that directed an FCC rulemaking action, rather than NIST standards, and which mandated industry use of the terms as the FCC defines them.8

In some of its more controversial recommendations, the NBP proposes that broadband success be measured not only by the statutory objective of “access to broadband capability,”9 but also by adoption percentages and affordability, using a national commitment to “inclusiveness” as the principal justification. “While it is important to respect the choices of those who prefer not to be connected, the different levels of adoption across demographic groups suggest that other factors influence the decision not to adopt. Hardware and service are too expensive for some. Others lack the skills to use broadband.”10 The FCC also proposes creation of a Digital Literacy Corps, modeled after President John F. Kennedy’s Peace Corps initiative, to educate minority and disadvantaged citizens on the use and importance of computers and Internet services. Having successfully subsidized the connection of more than 95 percent of America’s classrooms to the Internet, the FCC’s plan further recommends that the E-Rate program be expanded to cover off-campus network use, e-readers and a variety of even newer functions. Among the recommendations for congressional action, the highest price tag—up to $16 billion—would be for grants to cover capital and operational costs of an interoperable public-safety mobile broadband network. As was revealed previously, the NBP also proposes auctioning the 700-megahertz “D block” rather than allocating it to public safety and first-responder services.

There are likely to be numerous FCC notice-and-comment rulemakings, legislative hearings and policy workshops initiated over the next 12 to 18 months to implement the NBP. As Connecting America emphasizes in its executive summary:

Public comment on the plan does not end here. The record will guide the path forward through the rulemaking process at the FCC, in Congress and across the Executive Branch, as all consider how best to implement the plan’s recommendations. The public will continue to have opportunities to provide further input all along this path.

The FCC has stated it will publish a timetable of actions in the near future and is anticipated to begin what may be considered more challenging NPRM proceedings, such as USF reform, within 60 to 90 days. Whether in the IT, telecom, energy or healthcare industries, companies involved in a wide range of different markets are likely to be affected by the National Broadband Plan for years to come and should consider participating in the rulemaking and parallel legislative processes.

**[This is a client alert I prepared for my law firm, Duane Morris LLP, which holds the copyright. The alert is available here.]

Footnotes

- “President Obama Hails Broadband Plan,” Washington Post, March 16, 2010.

- Connecting America at xiv, 9.

- Connecting America at xiii.

- See, e.g., “FCC Chairman Genachowski Confident in Authority over Broadband, Despite Critics,” Washington Post, March 3, 2010.

- “FCC’s National Broadband Plan Raises Divisive Issues,” USA Today, March 17, 2010. Compare B. Reed, “Who Else Wants National Broadband?”, Business Week, March 16, 2010, with J. Chambers, “Why America Needs a National Broadband Plan,” Business Week, March 16, 2010.

- Connecting America at xiv.

- Connecting America at 35–36. “The FCC and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) should collect more detailed and accurate data on actual availability, penetration, prices, churn and bundles offered by broadband service providers to consumers and businesses, and should publish analyses of these data.” Id. at 35.

- T.R. Daily, March 15, 2010, at 2.

- ARRA § 6001(k)(2)(D), 123 Stat. 115, 516 (2009).

- Connecting America at 23.

Study Reports Americans Believe Internet Access Is a “Fundamental Right” [PCMagazine].

But in the United States, our political system does not even make food, shelter and clothing fundamental citizen (let alone human) rights. So where does anyone get off suggesting Congress or the FCC should declare that the Internet is something more important than the reality of basic human needs? This is a completely bogus debate and the “study” — an opinion poll, no less — is just irrelevant. Later I’ll tell you how I _really_ feel. 😉

Posted via email from glenn’s posterous

|

|