A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

Almost everyone realizes there is a federally managed “Do Not Call List” governing telephone marketers (or “telemarketers”). Less well known is that a 1991 law, the Telelephone Consumer Protection Act, 47 U.S.C. § 227, prohibits telemarketing calls using autoidialers without consent, unsolicited fax advertisements and telemarketing calls to cell phones. Combining this statute with class action procedures has resulted in some substantial damages judgments over the years.

The story of TCPA this year, though, is how the Supreme Court can sometimes see a legal issue so clearly despite confusion and conflicts among the lower federal courts. Earlier this term, the Court handed down a decision in Mims v. Arrow Financial Services LLC, in which it held that TCPA lawsuits can be brought in federal court pursuant to “federal question” jurisdiction. Although that same question had been answered in the negative by several courts of appeals — based on statutory language granting TCPA jurisdiction to state courts “if [such an action is] otherwise permitted by the laws or rules ofcourt of [that] state” — the Supreme Court’s decision was unanimous, 9-0, to the contrary. According to the Court’s opinion, since Congress had not divested federl courts of jurisdiction in the TCPA, state courts did not have excluisive jurisdiction over TCPA litigation because “the grant of jurisdiction to one court does not, of itself, imply that the jurisdiction is to be exclusive.”

There are some interesting themes of judicial temperment implicit in this holding, including a tendency (regardless of conservatism or political affiliation) for the federal judiciary to aggrandize its power despite constant reiteration of the concept of limited federal jurisdiction. What is remarkable about Mims, however, is more pragmatic. Even with the class action reforms of the past decade, federal courts still do a better job, especially for defendants, of administering nationwide class action cases. The Supreme Court has now given a green light to bringing these cases in federal district court. So the back-and-forth between federal and state court that has bedeviled TCPA litigants for years is now a thing of the past. Like the old Smith Barney commercials featuring John Houseman, when the Supreme Court talks, people listen.

Cross-posted from the Duane Morris Techlaw Blog.

This is the brief I just prepared for the Consumer Federation of America to the U.S. Supreme Court on the issue of whether the so-called Red Lion doctrine of First Amendment regulation of broadcasters should be re-examined. My favorite passage is:

[T]he presumption of invalidity inherent in petitioners’ argument is flawed. Broadcasters do not remain “singularly constrained,” Pet. at 16, on the ground that there were few speakers 45 years ago. When Red Lion was decided there were hundreds more newspapers in America, half a dozen or more in major cities like New York, national, weekly news and cultural magazines (Life, Look, etc.) and many other sources of information and entertainment that are no longer available in today’s marketplace. Therefore, the “undeniably large increase in the number of broadcast stations and other media outlets” on which the D.C. Circuit and petitioners rely, id. at 18, is immaterial to the economic regulation of broadcast licensees unless — as petitioners dare not suggest, because it is untrue — the increase has lessened the technical need for governmental entry and interference regulation.

Whether there are three or six or ten television stations in a local market, however, does not at all mean there is enough spectrum to accommodate everyone who would like to use the airwaves. What some judges have called “the indefensible notion of spectrum scarcity,” Action For Children?’s Television v. FCC, 105 F.3d 723, 724 n.2 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (Edwards, J., dissenting), is therefore totally true and completely defensible.

[slideshare id=11925599&doc=11-696cfaopp-brief-120308132113-phpapp02&type=d]

It is rare that the justices of the Supreme Court of the United States actually write or speak about technology. But as connectivity and user-generated content become more ubiquitous and pervasive, sometimes the Court — despite its inherent judicial conservatism — just can’t avoid touching on issues related to the use, importance and legal status of modern communications technologies.

In that respect, the just-completed 2009-10 and 2010-11 Supreme Court terms witnessed two rather impressive developments. First, while more than a year ago most of the justices, and especially Antonin Scalia, said they had never even heard of Twitter, 2010 saw the first-ever mention of blogs and “social media” in a Supreme Court opinion, namely the controversial Citizens United decision on corporate campaign spending.

Rapid changes in technology — and the creative dynamic inherent in the concept of free expression — counsel against upholding a law that restricts political speech in certain media or by certain speakers. Today, 30-second television ads may be the most effective way to convey a political message. Soon, however, it may be that Internet sources, such as blogs and social networking Web sites, will provide citizens with significant information about political candidates and issues. Yet, §441b would seem to ban a blog post expressly advocating the election or defeat of a candidate if that blog were created with corporate funds. The First Amendment does not permit Congress to make these categorical distinctions based on the corporate identity of the speaker and the content of the political speech.

Citizens United v. FEC, 130 S. Ct. 876, slip op. at 49 (2010) (emphasis added; citations omitted).

Second, in this spring’s ruling overturning California’s regulation of violent video game sales to minor children — a/k/a teenage gamers — a sharply divided Court grappled not with the previously undecided question of whether video games merit First Amendment protection (on which there was unanimity), but instead the far narrower one of how to show a “compelling state interest” in restricting speech directed to children. That led to a remarkable passage, from Scalia himself, which as is typical was relegated to a footnote (where the “good stuff” is often found):

Justice Alito accuses us of pronouncing that playing violent video games “is not different in ‘kind’” from reading violent literature. Well of course it is different in kind, but not in a way that causes the provision and viewing of violent video games, unlike the provision and reading of books, not to be expressive activity and hence not to enjoy First Amendment protection. Reading Dante is unquestionably more cultured and intellectually edifying than playing Mortal Kombat. But these cultural and intellectual differences are not constitutional ones. Crudely violent video games, tawdry TV shows, and cheap novels and magazines are no less forms of speech than The Divine Comedy, and restrictions upon them must survive strict scrutiny—a question to which we devote our attention in Part III, infra. Even if we can see in them “nothing of any possible value to society . . ., they are as much entitled to the protection of free speech as the best of literature.” Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507, 510 (1948).

Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Assn., slip op. at 9 n.4 (2011) (emphasis added).

So the lesson is that although Justice Scalia may not know how to Tweet, but he can spell perfectly the name of a classic martial arts videogame, while still believing that The Divine Comedy is of greater value to society. What would the modern, technophile generation think about that? We’ll probably never know, because those facile with the means for mobile and rapid communications have short attention spans and thus probably lack have the patience (interest aside) to read Dante, even the Cliff Notes version, and tell us!

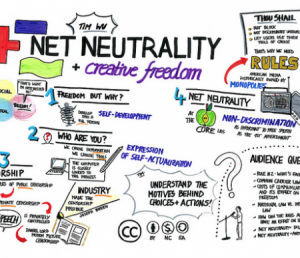

The news today is all about Tuesday’s “open meeting” at the FCC, where at long last a proposed regime for network neutrality will formally be considered. “There are of course a lot of moving pieces surrounding this debate, and however the chips fall, it’s going to have a long-term affect over how the Internet operates over the next several years.” The FCC Votes on Net Neutrality Tomorrow; The Internet Waits | AllThingsD.

Actually, the modest few rules FCC Chairman Genachowski has proposed are so trivial that, like all good policy, compromises or settlements, they have angered both the left and the right. The former deplores the scheme as worse than nothing, while the latter says it is a slippery slope to full regulation of the Internet.

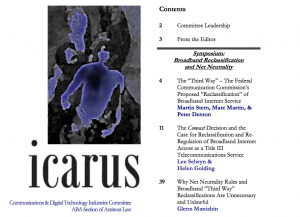

The far more important issue tomorrow is the legal framework under which the FCC will propose net neutrality rules. After the Comcast decision in April of this year — in which a federal court of appeals threw out the Commission’s decision to sanction undisclosed throttling of P2P traffic by ISPs — net neutrality has been in a state of extreme jurisdictional chaos. For an overview, read the Fall 2010 edition of the ABA’s Icarus magazine, a symposium issue on so-called “Title II reclassification” featuring, among others, this author.

About a month ago, Genachowski also announced has was abandoning his Third Way reclassification approach. That’s a brilliant decision, as reclassification was doomed to judicial reversal and, almost certainly, an injunction or stay against implementation. The alternative is for the FCC to articulate the ancillary jurisdiction linkage or nexus between the agency’s specific areas of delegated responsibility — telephony (Title II) and broadcasting (Title III) — and its general authority over “communications by wire or radio.” Yet to do that the agency needs to distance itself from the protectionist roots and core of the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, which for 40+ years has been used principally to squelch or constrain new technologies in order to prevent market competition with older, established industries (constituencies).

Here’s what I wrote earlier:

Ancillary jurisdiction under Southwestern Cable represents the low-water mark of communications jurisprudence. It was fashioned as a legal matter to permit FCC control of CATV, the infant predecessor to today’s robust cable programming industry, as a means of protecting the Commission’s power to regulate broadcast television. . . . It was protectionism to the core [and] epitomizes the conservative critique of administrative agencies as regulatory capture.

There is no longer an appetite in Congress to utilize governmental regulation to protect incumbents and vested commercial interests against competition and new entry. Hence, because it lacked and still lacks the political will to justify net neutrality on the ground of protecting its Title II and III jurisdiction over telephony and broadcasting — by sheltering the legacy providers of those services against disintermediation — the agency can never provide the requisite “nexus” demanded by the Comcast opinion.

Since no current policy or political figure today can admit to using regulation to handicap new entrants and favor established business interests, ancillary jurisdiction will remain the dark, dirty secret of administrative law until it is moved to a new footing. Imagine if the FCC reasoned that with IP convergence, services that formerly were within its Communications Act authority, like telephony and television, are increasingly moving to an Internet-based delivery system that, if it continues, will eventually leave all of communications beyond the FCC’s jurisdiction. Under this approach, the Commission could demonstrate a clear nexus between its statutorily delegated responsibilities and the ancillary role it proposes for net neutrality, without reverting to the sullied, protectionist past of ancillary jurisdiction.

Some observers may argue that such a “Title I” approach to net neutrality does not in principle prevent the FCC from exercising unlimited power over Internet communications. That’s overstated in my view. First, the Supreme Court’s 1970s decisions on ancillary jurisdiction (Midwest Video) hold that ancillary jurisdiction us not “unbounded.” Second, from a legislative perspective it is obvious that an administrative agency acting on the basis essentially of implied power cannot do anything broader under a general “public interest” standard than it could if acting under the express jurisdiction delegated by Congress. Specifically, while Title II authorizes full, rate-of-return common carrier regulation, the FCC would overstep its bounds imposing parallel rules under Title I ancillary jurisdiction. Third, the extreme critique from conservatives that agencies cannot be permitted to do anything without express congressional authorization really doesn’t apply; Congress has granted Title I authority over all interstate communications, it just has not fleshed that out with detailed standards.

More problematic are current reports that the FCC is considering relying on Section 706 of the Act, which urges the agency to promote “advanced telecommunications” services, as its ancillary jurisdiction hook for net neutrality. That’s inane, because the Commission in the 1990s ruled over and over again that 706 was not a basis for regulatory power. This means that using 706 as the nexus for ancillary jurisdiction will necessarily stoke a hotter fight over the FCC’s reversal of its statutory interpretation, a double whammy.

The better linkage is to the basic legislative commands (e.g., Section 201) that direct the FCC to ensure just and reasonable communications and broadcasting services for users. It cannot be disputed that if current trends continue, VoIP and Internet video could and well may eventually displace POTS and cable/broadcasting, in which case there would be nothing left with which the FCC could fulfill these elementary responsibilities if such IP-based services, which do not represent “telecommunications,” “cablecasting” or “broadcasting” in traditional statutory terms, must remain forever and completely unregulated.

A broader and more cogent question is, if the FCC takes this approach, would that not create a system in which an agency decides for itself how far to go when Congress fails to update its underlying statutory power to reflect technological change? Yes, it would. But it would not be Genachowski or the FCC creating this paradigm, it was the Supreme Court. A better legal system would have an administrative agency go back to Congress and ask for new powers if its old ones are being end-run by technology. As a practical matter, that could lead to gridlock, however, as in the communications arena general revisions of the Communications Act of 1934 happen very rarely — once in 65 years, far less than every generation.

So if politics is the art of the possible, it is possible for the FCC this Tuesday to make history, survive a judicial challenge and move archaic regulatory jurisprudence forward into a new era, stripped of its protectionist past. It’s also possible the Commission will be split politically, that left-wing proponents can convince some members that a principled loss is better than a compromise win, see Net Neutrality Supporters Question FCC’s Genachowski Plan | Techworld.com, or that as it has so many times in the past, the agency will fail to explain itself in simple terms the courts demand and can understand.

The Third Way of Title II reclassification was too cute for its own good. The Commission has a chance to correct that overreaching, but its internal bureaucratic tendencies to ambiguity and a “Chinese menu” theme for jurisdiction threaten to blow up net neutrality again. GOP Opposition to FCC Net Neutrality Plan Mounts | enterprisenetworkingplanet.com. Far more principled, regardless of one’s position on the substantive merits and policy need for network neutrality, would be for the FCC to pick a single, simple nexus. It’s not cute, it’s not expansive, but it would work. The question is whether in this highly polarized legal and political environment, the players really want anything to work at all.

Politics is always, in part, theater and sausage-making. That the law and public policy are the byproducts of such superficial pursuits remains a frustration, but in the United States it’s one we all have to live with, and one some pundits are convinced preserves the republican tradition of limited government. I for one hope the FCC keeps a more modest agenda tomorrow and moves the net neutrality debate closer to a conclusion, instead of adding fuel to the legal and policy fires that have raged on this issue for years.

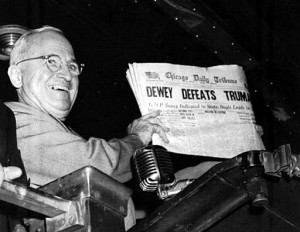

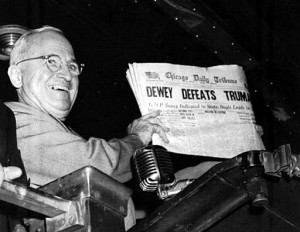

60 years ago, when Harry Truman beat Tom Dewey for the presidency, it was widely predicted by pollsters that Truman would lose. This led to the famous “Dewey Beats Truman” headline in the newspaper proudy flashed by the winning candidate.

The problem, it was later revealed, was that the Gallup organization based its poll results on responses to telephone inquiries. But in the late 1940s, that selection inevitably favored wealthier Republicans, leading to skewed poll results.

Gallup is best known for that one half-century-old blunder. There’s a terrible irony in that. The studious George Gallup did more than anyone to put opinion polling on solid ground.

We have a similar problem today, it appears to me. While telephone subscribership has now become ubiquitous, increasingly many citizens — especially twenty-somethings — no longer use landline telephones, instead going completely wireless. The proportion was 1 in 6 three years ago and continues to increase steadily. Pollsters, however, still base their surveys on landline phone subscribers. In fact, under FCC regulations it is unlawful to telephone a wireless subscriber for a “solicitation” or using an autodialer (a technical prerequisite to modern polling) without either their consent or a prior business relationship. Therefore, despite a non-profit exemption in the FCC’s rules (which, unlike the Federal Trade Commission’s “telemarketing sales rule,” do not expressly exempt political polling), the law is standing in the way of accurate political predictions.

How this will play out in next Tuesday’s elections is unclear to me, as I claim no special expertise in political punditry. But it is revealing that the problems experienced in 1948 are recurring today in a different form due to technological change and the accelerating proliferation of wireless communications devices.

This is the opening paragraph of an article by this author appearing today in the Fall 2010 issue of Icarus, the newsletter of the ABA’s Communications & Digital Technology Industries Committee, Section of Antitrust Law. “If the issue of broadband reclassification is not addressed with sensitivity to the history and traditions of FCC common carrier regulation, one can all too easily arrive at conclusions that simply cannot be squared with the legal framework applied to telecommunications for more than 30 years.”

The highly polarized debate over so-called net neutrality at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) exposes serious philosophical differences about the appropriate role of government in managing technological change. Neither side is unfortunately free either from hyperbole or fear-mongering. And neither side is completely right.

Read the whole essay. It’s provocative.

Note: I have not appeared as counsel for any party to the FCC’s current net neutrality NOI proceeding and was not paid to write this essay (despite what my colleagues and clients in the public interest community may claim). I represented Google in the past but now am ethically precluded from doing so because my law firm has a conflict of interest, being adverse to Google in an employment age discrimination case before the California Supreme Court. The article nonetheless does not reflect the views or opinions of my firm or any of my clients, past or present.

It is completely beyond my why the Obama Administration and congressional Democrats could be this obtuse. No one should want — and I doubt any American really does support — the government standardizing serving sizes and recipe compositions, even on health grounds.

Remarkably, Section 4205 of the new health reform law, which requires chain restaurants and vending machines to provide nutrition notices, instructs the HHS Secretary to:

Consider standardization of recipes and methods of preparation, in reasonable variation in serving size and formula of menu items, space on menus and menu boards, inadvertent human error, training of food service workers, variations in ingredients…

HHS Secretary to Regulate Serving Sizes and Recipes for Cheeseburgers and Fries | John Goodman. Who could have known? That’s in part because the provision literally was buried:

You’ve heard the phrase “buried in the bill,” of course. Section 4205 of the “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,” the health care reform bill President Obama signed on March 23, 2010 is contained on pages 1206-14 of a 2407 page bill. It could hardly be more buried than that.

Food Lability Law Blog.

And so, America has gone from “Cheeseburger in Paradise” to “I Can Has Cheeseburger” to self-proclaimed “reformer” rants against Five Guys burgers as Xtreme Eating. What a country! It’s all well and good that Ms. Obama’s pet issue is childhood obesity, but outlawing fatty and big meals will, like illegal drugs, just make them more desirable. So this proposal for more government will inevitably backfire, as well as being totally repulsive from a civil liberties standpoint.

In a decision that has already generated a huge volume of commentary and predictions,1/ just three days ago the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit reversed a contentious ruling by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) from 2008 that penalized Comcast Corp. for violating the Commission’s “network neutrality” Internet principles. Comcast Corp. v. FCC, No. 08-1291 (D.C. Cir. April 6, 2010). Those principles include a content access requirement that the FCC said prohibited broadband operators and other Internet Service Providers (ISPs) from using network management practices to block or “throttle” specific Internet Protocol (IP) based services, such as the peer-to-peer, or P2P, filing-sharing communications offered by BitTorrent.

The Court’s opinion represents a devastating blow to the FCC’s assertion of ancillary jurisdiction authority over the Internet, ISPs and IP-based services. It calls into question how, if at all, the agency can implement many of the proposals put forward in its recent National Broadband Plan (NBP) and the “open Internet” proceeding launched last fall to codify those 2005 net neutrality principles (plus two additional rules proposed by new FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski). And the D.C. Circuit decision calls out for resolution by Congress of the jurisdictional void created — a call some legislators have already heeded.2/

Yet much of this crisis mentality appears unwarranted. There are accepted legal bases the FCC could employ to achieve a substantial part of its objectives related to consumer protection on the Internet. Where the FCC may not by statute operate, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) — which for several years has been biting at the bit to oversee broadband competition and consumer protection — can. That is because the Comcast decision compels the conclusion, at the very least, that broadband is not a “common carrier” service over which the FCC enjoys exclusive federal jurisdiction. The FCC’s proposal in its recent broadband plan that the agency apply universal service funds to subsidize broadband deployment in rural areas is likely not threatened materially by the Comcast decision. And the larger public policy fight over so-called “reclassification” of broadband as a Title II service presupposes, incorrectly, that Title II treatment means subjecting IP-based services to the same, traditional public utility model of regulation as monopoly telephone providers. In short, the agency and Congress face a dizzying array of alternatives and options. Yet much of this crisis mentality appears unwarranted. There are accepted legal bases the FCC could employ to achieve a substantial part of its objectives related to consumer protection on the Internet. Where the FCC may not by statute operate, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) — which for several years has been biting at the bit to oversee broadband competition and consumer protection — can. That is because the Comcast decision compels the conclusion, at the very least, that broadband is not a “common carrier” service over which the FCC enjoys exclusive federal jurisdiction. The FCC’s proposal in its recent broadband plan that the agency apply universal service funds to subsidize broadband deployment in rural areas is likely not threatened materially by the Comcast decision. And the larger public policy fight over so-called “reclassification” of broadband as a Title II service presupposes, incorrectly, that Title II treatment means subjecting IP-based services to the same, traditional public utility model of regulation as monopoly telephone providers. In short, the agency and Congress face a dizzying array of alternatives and options.

This post has two parts:

- First, I review the proceedings leading up to and the substance of Circuit Judge David S. Tatel’s opinion for a unanimous three-judge panel of the court of appeals.

- Second, I put the decision into context and explore ways in which the FCC could react, including the legal rationale(s) the agency would need to develop on remand.

Both portions of the essay, however, are of necessity general overviews. A complete examination of this rather wonk-ish area of communications jurisprudence requires a longer treatise than warranted for such a time-sensitive post. I encourage readers to address these issues in greater detail in comments below and to the FCC in its open Internet NPRM proceeding.

1. The Comcast Decision

The FCC had classified cable modem service as an information service under the bifurcated regulatory approach of Computer II and the 1996 Telecommunications Act, a ruling affirmed by the by the Supreme Court in NCTA v. Brand X, 545 U.S. 967 (2005). Nonetheless, the Commission later developed a set of four network neutrality principles adopted in a 2005 “policy statement.” These were intended to protect what the agency perceived as a threat to the open character of the Internet if vertically integrated content providers blocked or discriminated against other Web sites and content in order to favor their own IP-based services.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network.

- To encourage broadband deployment and preserve and promote the open and interconnected nature of the public Internet, consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

Much like the assumptions underlying the NBP, the net neutrality principles aspired to an Internet free of any provider’s control, giving every end user access — with little or no permissible differentiation among services or even packets — to all content available anywhere, anytime. (They also harkened to a similar failed effort by public interest advocates, in the late 1990s, for what was then termed “cable open access.”)

Whether or not regulatory intervention is needed to ensure this result was not at issue in the Comcast appeal, but it was central to the FCC’s enforcement action that triggered the case. Faced with the reality that file-sharing end users were consuming huge amounts of bandwidth, Comcast deliberately limited their ability to use P2P client-side applications by first outright blocking, and later imposing network management controls on, BitTorrent IP traffic, so that the latency-sensitive applications of the majority of its Internet customers would be delivered uninterrupted. Some consumer advocates alleged that the cable giant did so in order to protect its own on-demand video programming services from potential competition. Comcast stopped the practice after the story came out but was later discovered to have misled the Commission with its initial responses, and the company never revealed to customers that some IP traffic was not being routed with the same throughput as other services. The FCC subsequently imposed reporting and disclosure requirements on Comcast’s traffic management practices, based on the 2005 policy statement, which the agency had not promulgated as actual rules or regulations.

Comcast appealed that decision. The FCC defended its actions on the ground that, even though Internet broadband is not a telecommunications service subject to Title II of the Act, the agency has ancillary jurisdiction to regulate. That ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, sometimes confusingly referred to as “Title I jurisdiction,” is based on a 1960s-era decision by the Supreme Court in which the FCC had restricted cable television by regulation in order to protect traditional TV broadcasters, over which the agency enjoyed express statutory authority. In Comcast, the D.C. Circuit concluded that under that approach, ancillary regulations must be ancillary to something explicit in the Act, in other words that the Commission must show that its traffic management directive was “reasonably ancillary to the … effective performance of its statutorily mandated responsibilities.” Finding that the FCC had not done so, the Court reversed.

Without detailing each of the statutory hooks advanced by the Commission, it suffices to say that the agency did not seriously urge the court of appeals to sustain ancillary Internet regulation in order to protect its Title II, III (broadcasting) or VI (cable) jurisdiction over legacy services for which the Communications Act grants explicit regulatory authority. Instead the FCC urged that various general statements of public policy appearing in the 1996 Act amendments provided the necessary linkage. The D.C. Circuit rejected that contention, concluding that policy does not suffice under the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine as a statutorily mandated responsibility. The FCC also cited section 706 of the 1996 Act, which directs it to “encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans.” The Court likewise rejected that linkage because the Commission itself had long ago ruled that section 706 does not constitute “an independent grant of authority” to the agency.

These holdings, foreshadowed earlier by oral argument — see “Appeals Court Unfriendly To FCC’s Internet Slap At Comcast” [Wall Street Journal] — are relatively unsurprising. What is somewhat unusual is that, in its appellate positions, the FCC suggested additional grounds for an ancillary jurisdiction theory that had not been relied on in its 2008 order. The most cogent of these added rationales was that Internet openness and nondiscrimination is ancillary to the “just and reasonable practices” mandate of sections 201(b) and 202(a), applicable to telecom carriers. Judge Tatel’s opinion dismissed these post-hoc justifications not on the substance, but rather because Administrative Procedure Act precedent requires a reviewing federal court to sustain or reverse a regulatory order on the same grounds offered by the agency in its underlying decision.

Comcast’s challenge of the 2008 order had offered the Court the opportunity to overturn it on the narrower ground that principles, unlike rules, are not enforceable in company-specific adjudications. But the D.C. Circuit did not reach that question. Its analysis essentially concurred with dissenting Commissioner Robert McDowell’s criticism that “[u]nder the analysis set forth in the order, the FCC apparently can do anything so long as it frames its actions in terms of promoting the Internet or broadband deployment.”3/

The end result is that the FCC’s network neutrality principles are effectively dead, for now at least. The agency has various options available, but unless and until it develops either an alternative rationale under its existing statutory framework, or procures a new legislative grant of authority from Congress, it cannot police the practices of ISPs and broadband providers. It is to these alternatives and their viability that I now turn.

2. The Post-Comcast Regulatory & Legislative Environment

In the wake of the D.C. Circuit’s decision, network neutrality advocates urged the FCC to ensure Internet openness by “reclassifying” broadband as Title II telecom service. Gloating opponents opined that the FCC was properly chastised and should rein in its efforts to regulate what they view as an increasingly competitive market, in which most major ISPs have long ago pledged to respect net openness as a business matter. Meanwhile, Web-based grassroots campaigns, with typical rhetorical excesses, sprang up overnight to “save Internet freedom.”

The reality is somewhere in between. Had the FCC desired, it could have — and still might — justify its ancillary jurisdiction by articulating a relationship between broadband Internet access and traditional, regulated communications services. By declining to review the Obama Commission’s arguments based on the mandatory obligations of reasonable rates and practices under Title II, the court of appeals has all but begged the FCC to do so on remand. The problem with this approach, especially given the history of the ancillary jurisdiction doctrine, is that it reflects a paternalistic, corporate welfare model of economic regulation which is out of favor as a policy matter with politicians, regardless of their party affiliation or ideology.

It would not, however, require much in the way of legislation to give the FCC explicit authority to adopt and impose network neutrality nondiscrimination rules. In its 2009 stimulus legislation, Congress allocated $7.2 billion for distribution by executive branch agencies in the form of grants to spur broadband deployment. A portion of those funds was expressly conditioned on grantees’ agreement in advance to comply with the Commission’s 2005 network neutrality principles. Unlike broader calls to completely rewrite the Communications Act in light of convergence, a legislative “fix” specific to net neutrality would not be unusually difficult. Whether there exists the political will and votes to do so, especially in the aftermath of the divisive healthcare reform debate, is unclear.

Nor does the Comcast decision by the D.C. Circuit necessarily spell the death knell for the Commission’s National Broadband Plan. Some of its proposals, such as privacy protections for broadband end users and truth-in-billing disclosure requirements for ISPs, would surely require new legislative authority. Yet the basic objectives of the plan, including its proposal to allocate an additional $16 billion in universal service funds to subsidize broadband services, are not necessarily invalid after Comcast. That is because section 254 of the Act likely allows the FCC to both collect USF contributions from and — as reflected in the E-rate program — use them for “advanced services” like Internet access. Nor does the Comcast decision by the D.C. Circuit necessarily spell the death knell for the Commission’s National Broadband Plan. Some of its proposals, such as privacy protections for broadband end users and truth-in-billing disclosure requirements for ISPs, would surely require new legislative authority. Yet the basic objectives of the plan, including its proposal to allocate an additional $16 billion in universal service funds to subsidize broadband services, are not necessarily invalid after Comcast. That is because section 254 of the Act likely allows the FCC to both collect USF contributions from and — as reflected in the E-rate program — use them for “advanced services” like Internet access.

The final FCC option is to reconsider its earlier rulings that Internet access services (at least when integrated with IP transport) are “information services” for purposes of the 1996 Act’s classifications. Some analytical jujitsu would obviously be required to achieve that result, since the agency needs to develop and articulate changed circumstances that rationally justify a reversal of its prior ruling. But since the Supreme Court has recently emphasized that the APA does not impose on administrative agencies any higher burden of justification to repeal or revise its rules and policies than to adopt them in the first place, the FCC conceivably might be able to satisfy that standard.

Much of the opposition to this sort of “reclassification” stems from the fear that characterizing Internet access as a telecommunications service would carry with it the full panoply of legacy Title II dominant carrier regulation, such as rate-of-return pricing, entry and exit licensing and the like. The two, however, are not co-extensive. It has been the law for several decades, codified by Congress in 1996, that the FCC enjoys the ability to refrain or “forbear” from regulation. Reclassifying broadband as a Title II telecom service could, at least hypothetically, be coupled with a simultaneous decision forbearing from application of most substantive regulations to ISPs.4/ Yet at least to public interest advocates, that would be viewed as a loss; in their regulatory paradigm broadband represents the new common carriage and should be offered on a quasi-utility basis. That perception will need to be changed if proponents of reclassification are to stand a realistic chance of persuading the agency and, more importantly, successfully withstanding judicial review.

Finally, under both the Bush and Obama Administrations the FTC has expressed a clear desire to exercise its own statutory jurisdiction over broadband services. Historically, the FTC is precluded from applying the Federal Trade Commission Act and its unfair competition and consumer protection standards to common carriers. But absent reclassification, broadband is plainly not a common carrier service under either the Communications Act or the FTC Act. As a result, although FTC Chairman John Liebowitz has not made a public statement to date in the wake of Comcast, most observers expect that agency to move relatively rapidly into broadband for purposes of filling the void left in the wake of the court of appeals’ decision.

Conclusion

Network neutrality is a complex, contentious and confusing issue. While the D.C. Circuit’s opinion is abundantly clear, it is not apparent how the FCC or Congress will respond and whether the agency will seek Supreme Court certiorari review to test the basis and scope of its ancillary jurisdiction. Having persisted formally since 2005, and as a matter of policy debate for more than a decade, net neutrality is not necessarily dead, it is just entering a new phase of consciousness. That it looks comatose is perhaps a mirage that will be evaporated with time.

Footnotes

1/ Court Limits FCC Power Over Internet,” Boston Globe, April 7, 2010; Editorial, “FCC Must Quickly Reclaim Authority Over Broadband,” San Jose Mercury News, April 7, 2010; “FCC to Start Writing Internet Rules After U.S. Court Setback,” Business Week, April 8, 2010.

2/ Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), chair of the House Committee on Energy & Commerce, announced almost immediately that he is “working with the Commission, industry, and public interest groups to ensure that the Commission has appropriate legal authority to protect consumers.” Waxman Statement, April 6, 2010. Earlier, in July 2009, Reps. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) and Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.) introduced H.R. 3458, the Internet Freedom Preservation Act of 2009, to enshrine what the legislation terms “Internet freedom” into law. However, In 2006 Congress failed to pass five bills, backed by groups including Google, Amazon.com, Free Press and Public Knowledge, that would have handed the FCC the power to oversee network neutrality compliance.

3/ See also R. McDowell, “Hands Off the Internet,” Washington Post, April 8, 2010.

4/ In response to concerns voiced regarding reclassification, Rep. Markey said that even under Title II, the FCC could forbear if it wanted to” and that in the past it had “availed itself” of that power. “We shouldn’t pretend that going back to Title II would mean that the earth would stop spinning on its axis and it would be the end of times,” he added. See “Concerns About Title II Reclassification Aired at House Hearing on Broadband Plan,” T.R. Daily, April 8, 2010.

Earlier this week, one month after originally scheduled and following a year of study based on more than 30 requests for public comment — generating some 23,000 comments totaling about 74,000 pages from more than 700 parties — the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) released a 360-page report to Congress on broadband Internet access services. The National Broadband Plan (NBP) encompasses more than 200 recommendations for how Congress, other government agencies and the FCC can improve broadband availability, adoption and utilization, especially for meeting such “national purposes” as economic opportunity, education, energy and the environment, healthcare, government performance, civic engagement and public safety.

Titled Connecting America and praised on its publication by President Obama,1 the NBP presents a wide range of legal, policy, financial and technical proposals, all devoted to meeting the legislative order—first articulated in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA)—of recommending ways to make broadband ubiquitous for Americans. Much of the general outlines and major recommendations of the plan were revealed in a series of public appearances and media briefings by FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski over the past several weeks. Only the NBP’s executive summary was made available before the full plan’s official March 16 publication. The public release of the entire document reveals the whole plan, including details on the recommendations as well as the reasoning behind them and the FCC’s goals.

The ambitious NBP sets as a national goal the delivery to all Americans of 100 megabits per second (Mbps) Internet service within 10 years, informally known as the “10 squared” objective. Its premise is that “[l]ike electricity a century ago, broadband is a foundation for economic growth, job creation, global competitiveness and a better way of life.”2 The policies and actions recommended in the plan fall into three major categories: fostering innovation and competition in networks, devices and applications; redirecting assets that government controls or influences in order to spur investment and “inclusion”; and optimizing the use of broadband to help achieve national priorities.

The FCC’s plan addresses wide range of interrelated issues, such as intercarrier compensation, universal service reform, spectrum reallocation (making 500 megahertz of spectrum newly available for broadband within 10 years), digital literacy, E-Rate (Schools and Libraries Program of the Universal Service Fund) services, set-top-box unbundling, affordability, “smart grid” electrical services, telemedicine, state and municipal broadband networks, distance education, wireless data services, homeland security and first-responder communications, wireless connectivity to digital-learning devices, Internet anonymity and privacy, data-center energy efficiency, video “gateway” network interface devices, and use of unlicensed spectrum (such as WiFi). The plan includes a proposal for the federal government to repurpose $15.5 billion in existing telecom-industry subsidies away from traditional landline telephone services to broadband, concluding that—

If Congress wishes to accelerate the deployment of broadband to unserved areas and otherwise smooth the transition of the [Universal Service] Fund, it could make available public funds of a few billion dollars per year over two to three years.3

Release of the NBP marks the start of what is likely to be a long and hotly debated implementation process, as the plan pits the interests of different industry segments against one other and tests the limits of the FCC’s regulatory authority.4 While lauding the plan’s aspirations, some critics in the first days after its release include broadcast television stations that are being asked to “voluntarily” relinquish valuable digital spectrum, satellite and cable companies that object to further regulation of their so-called navigation devices and rural telephone providers that are concerned with the potential loss of substantial Universal Service Fund (USF) revenues. Information technology (IT) and content delivery networks (CDNs) also have expressed concern that the FCC’s related net neutrality initiative would circumscribe their ability to offer quality of service (QoS) and packet-prioritized media services. Free-market advocates (both think tank and government) as well as Republican FCC Commissioner Robert McDowell have already declared that the plan is unnecessary or at least unnecessarily regulatory.5

Connecting America details a series of economic and public policy goals for the United States, which according to some studies has fallen in penetration and “adoption” of broadband Internet services from first in the world in the late 1990s to somewhere between 15th place to 20th place as of 2008.6 These goals are highlighted below.

- At least 100 million U.S. homes should have affordable access to actual download speeds of at least 100 Mbps and actual upload speeds of at least 50 Mbps.

- The United States should lead the world in mobile innovation, with the fastest and most extensive wireless networks of any nation.

- All Americans should have affordable access to robust broadband service, and the means and skills to subscribe if they so choose.

- Every American community should have affordable access to at least 1 gigabit per second broadband service to anchor institutions, such as schools, hospitals and government buildings.

- To ensure the safety of the American people, every first-responder should have access to a nationwide, wireless, interoperable broadband public-safety network.

- To ensure that America leads in the clean-energy economy, all Americans should be able to use broadband to track and manage their real-time energy consumption.

All of these goals are supported by proposals for the federal government to become more deeply involved in collecting and assessing statistical metrics on the availability, speed and use of broadband services and that the FCC impose “performance disclosure requirements” and “performance standards” on broadband service providers, including wireless and cellular carriers.7 As the trade publication Telecommunications Reports notes:

This recommendation illustrates how the plan could bump up against independent congressional initiatives. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D.-Minn.) introduced a broadband performance management bill along similar lines that directed an FCC rulemaking action, rather than NIST standards, and which mandated industry use of the terms as the FCC defines them.8

In some of its more controversial recommendations, the NBP proposes that broadband success be measured not only by the statutory objective of “access to broadband capability,”9 but also by adoption percentages and affordability, using a national commitment to “inclusiveness” as the principal justification. “While it is important to respect the choices of those who prefer not to be connected, the different levels of adoption across demographic groups suggest that other factors influence the decision not to adopt. Hardware and service are too expensive for some. Others lack the skills to use broadband.”10 The FCC also proposes creation of a Digital Literacy Corps, modeled after President John F. Kennedy’s Peace Corps initiative, to educate minority and disadvantaged citizens on the use and importance of computers and Internet services. Having successfully subsidized the connection of more than 95 percent of America’s classrooms to the Internet, the FCC’s plan further recommends that the E-Rate program be expanded to cover off-campus network use, e-readers and a variety of even newer functions. Among the recommendations for congressional action, the highest price tag—up to $16 billion—would be for grants to cover capital and operational costs of an interoperable public-safety mobile broadband network. As was revealed previously, the NBP also proposes auctioning the 700-megahertz “D block” rather than allocating it to public safety and first-responder services.

There are likely to be numerous FCC notice-and-comment rulemakings, legislative hearings and policy workshops initiated over the next 12 to 18 months to implement the NBP. As Connecting America emphasizes in its executive summary:

Public comment on the plan does not end here. The record will guide the path forward through the rulemaking process at the FCC, in Congress and across the Executive Branch, as all consider how best to implement the plan’s recommendations. The public will continue to have opportunities to provide further input all along this path.

The FCC has stated it will publish a timetable of actions in the near future and is anticipated to begin what may be considered more challenging NPRM proceedings, such as USF reform, within 60 to 90 days. Whether in the IT, telecom, energy or healthcare industries, companies involved in a wide range of different markets are likely to be affected by the National Broadband Plan for years to come and should consider participating in the rulemaking and parallel legislative processes.

**[This is a client alert I prepared for my law firm, Duane Morris LLP, which holds the copyright. The alert is available here.]

Footnotes

- “President Obama Hails Broadband Plan,” Washington Post, March 16, 2010.

- Connecting America at xiv, 9.

- Connecting America at xiii.

- See, e.g., “FCC Chairman Genachowski Confident in Authority over Broadband, Despite Critics,” Washington Post, March 3, 2010.

- “FCC’s National Broadband Plan Raises Divisive Issues,” USA Today, March 17, 2010. Compare B. Reed, “Who Else Wants National Broadband?”, Business Week, March 16, 2010, with J. Chambers, “Why America Needs a National Broadband Plan,” Business Week, March 16, 2010.

- Connecting America at xiv.

- Connecting America at 35–36. “The FCC and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) should collect more detailed and accurate data on actual availability, penetration, prices, churn and bundles offered by broadband service providers to consumers and businesses, and should publish analyses of these data.” Id. at 35.

- T.R. Daily, March 15, 2010, at 2.

- ARRA § 6001(k)(2)(D), 123 Stat. 115, 516 (2009).

- Connecting America at 23.

Hearing Room It is hard to understand how “conference reports” from Congress on pending legislation can have fallen from 200 per year to just 11 over the past three decades. Secret Bill Writing On the Rise [Washington Post]. But it indicates, sadly, that laws in America are increasingly being made in back rooms, not the public forums our system of politics has traditionally used. That may be mere window-dressing, but it is IMPORTANT symbolically, in my view.

In a letter to C-SPAN Chairman Brian Lamb, House Republican leader John Boehner wrote, “Unfortunately, the president, Speaker (Nancy) Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader (Harry) Reid now intend to shut out the American people at the most critical hour by skipping a bipartisan conference committee and hammering out a final health care bill in secret.” The complaint sounded a lot like one nine years ago, when Sen. Kent Conrad, D-N.D., said Republicans “locked out the Democrats from the conference committee” meeting on the budget. “We were invited to the first meeting and told we would not be invited back, that the Republican majority was going to write this budget all on their own, which they have done. So much for bipartisanship.”

|

|