A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

The strangely named Rockstar Consortium has been in the news again, in part because some of its members just formed a new lobbying group, the Partnership for American Innovation, aimed at preventing the current political furor over patent trolls from bleeding into a general overhaul of the U.S. patent system. Yet Rockstar is perhaps the most aggressive patent troll out there today. Hence the mounting pressure in Washington, DC for the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division — which signed off on the initial formation of Rockstar two years ago — to open up a formal probe into the consortium’s patent assertion activities directed against rival tech firms, principally Google, Samsung and other Android device manufacturers.

Usually the fatal defect in antitrust claims of horizontal collusion is proving that competing firms acted in parallel fashion from mutual agreement rather than independent business judgment. In the case of Rockstar — a joint venture among nearly all smartphone platform providers except Google — that problem is not present because the entity itself exists only by agreement among its owner firms. The question for U.S. antitrust enforcers is thus the traditional substantive inquiry, under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, whether Rockstar’s conduct is unreasonably restrictive of competition.

Despite its cocky moniker, Rockstar is simply a corporate patent troll hatched by Google’s rivals, who collectively spent $4.5 billion ($2.5 billion from Apple alone) in 2012 to buy a trove of wireless-related patents out of bankruptcy from Nortel, the long-defunct Canadian telecom company. It is engaged in a zero-sum game of gotcha against the Android ecosystem. As Brian Kahin explained presciently on DisCo then, Rockstar is not about making money, it’s about raising costs for rivals — making strategic use of the patent system’s problems for competitive advantage. Creating or collaborating with trolls is a new game known as privateering, which allows big producing companies to do indirectly what they cannot do directly for fear of exposure to expensive counterclaims. Essentially, it’s patent trolling gone corporate. As another pro-patent lobbying group said at the time, Rockstar represents “a perfect example of a ‘patent troll’ — they bought the patents they did not invent and do not practice; and they bought it for litigation.” Predictiv’s Jonathan Low put it quite well in his The Lowdown blog:

The Rockstar consortium, perhaps more appropriately titled “crawled out from under a rock,” is using classic patent troll tactics since their own technologies and marketing strategies have fallen short in the face of the Android emergence as a global power. Those tactics are to buy patents in hopes of finding cause, however flimsy, to charge others for alleged violations of patents bought for this purpose. Rockstar calls this “privateering” in order to distance itself from the stench of patent trolling, but there are no discernible differences.

Continue reading Rockstar’s Patent Trolling Conspiracy

Google’s competitors “are locked in hand-to-hand combat with Google around the world and have the mistaken belief that criticizing us will influence the outcome in other jurisdictions.”

The coalition of companies that for years has unsuccessfully been pressing antitrust complaints against Google for search “abuse” — FairSearch.org — insists Google must be restrained for fear the Mountain View company will steer search users to its commercial products, like flight bookings. The group’s most recent publicity event, held at the ABA’s Antitrust Section annual spring meeting last week, repeated those same claims. FairSearch ventured as well into new ground, attacking what it terms Google’s unreasonably restrictive Android licensing practices.

There are four straightforward reasons FairSearch is wrong.

1. Predictions of Foreclosure Have Proven Totally Baseless.

When Google purchased travel software maker ITA in 2011, FairSearch maintained that Google would exploit its control over the ITA tools that power other online travel agencies, along with many of the airlines’ own sites, to usher competing search services off the stage, then jack up ad rates for travel queries and favor flights from particular airlines.  Three years later, nothing like that has happened. In fact, Google Flight Search is not among the top 100 or even the top 200 travel listing sites. Rather, it’s in 244th place, behind Hipmunk, with just .04% of travel queries. Real-world experience, in other words, reveals that the predicted competitive risks on which FairSearch bases its advocacy are both hypothetical and fanciful. Continue reading Four Reasons Fairsearch Is Wrong Three years later, nothing like that has happened. In fact, Google Flight Search is not among the top 100 or even the top 200 travel listing sites. Rather, it’s in 244th place, behind Hipmunk, with just .04% of travel queries. Real-world experience, in other words, reveals that the predicted competitive risks on which FairSearch bases its advocacy are both hypothetical and fanciful. Continue reading Four Reasons Fairsearch Is Wrong

This is hilarious, and not altogether far-fetched. As the authors ask, wouldn’t it be interesting if Siri, the most famous example of artificial intelligence, had her deposition taken in litigation against Apple claiming the technology did not work as advertised?

Courtesy of my friends at Gallivan, White & Boyd, P.A. and their Abnormal Use blog. See also Lawsuit Claims Siri Doesn’t Know What She’s Talking About | Forbes.

My Troutman Sanders colleagues have written before on the continuing judicial wrangling over whether GPS tracking devices, as well as location data maintained by wireless telecom providers, require a warrant before search and seizure by the government. Last July, a New York state court ruled that a government employer did not need a warrant to attach a GPS device to an employee’s car and monitor his movements continuously for a month, contradicting an earlier decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court. More recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held — after a thorough review of precedent dating all the way back to 1981 — that law enforcement agents must indeed first obtain a warrant based on probable cause to attach a GPS device to a criminal suspect’s vehicle.

Cases dealing with this issue merit watching because they represent the “front lines” of the intersection between personal privacy and technological capability. The Supreme Court in United States v. Jones, 131 S. Ct. 3064 (2011), decided that GPS tracking generally requires a warrant,  but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider. but left open the more important question whether warrantless use of GPS devices would be “reasonable — and thus lawful — under the Fourth Amendment where officers have reasonable suspicion, and indeed probable cause,” to execute such searches. Meanwhile, a divided Fifth Circuit Court ruled in 2013 that the government may compel a wireless company to turn over 60-days worth of cell phone location data without establishing probable cause, while just last week the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their phones and thus, under the state constitution, law enforcement needs a warrant before obtaining location data from a suspect’s wireless provider.

So what does all this mean for the business community? Although law enforcement and the rather esoteric realm of constitutional law has been at the front lines of GPS privacy, there are a number of developments indicating that location privacy is also an important business issue:

First, the Federal Trade Commission — which functions as the de facto privacy regulator in the United States — has launched an inquiry into GPS tracking with a seminar convened on February 19 in Washington, D.C. This followed an FTC staff report last year, titled Mobile Privacy Disclosures: Building Trust Through Transparency, which “recommended” that companies consider offering a Do Not Track (DNT) mechanism for smartphone users among other measures to protect location privacy. Since the FTC has authority over unfair trade practices, including privacy, in almost every industry other than telecommunications, this initiative portends a risk of administrative sanction for private businesses not offering consumer choice as part of location-based services.

Second, HTC and Samsung smartphones come pre-loaded with software from the company Carrier IQ. More than 100 lawsuits filed since 2011 in federal court claim the phones unlawfully track the keystrokes of text messages and Internet searches. While the company maintains that the data are collected for customer support and to help troubleshoot network problems, it has become embroiled in litigation despite serving only as a technology vendor to other, far larger firms. (Not to leave them out, both Microsoft and Apple have also been sued over the location tracking features of their phones.) The lesson of Carrier IQ is that businesses are at risk in the GPS space even where they are not consumer-facing enterprises.

Third, a number of start-ups (Turnstyle, RetailNext, Nomi, shopkick, etc.) offer brick-and-mortar retailers the ability to use indoor location sensors and security video feeds to track movements of shoppers, recreating in the retail realm the same in-depth data on customer behavior that online merchants have long collected. Some of these firms follow best-practices by obtaining explicit opt-in for location information sharing. But the potential for adverse consumer reaction, and class action litigation, remains high ever since Nordstroms was caught in a PR whirlwind in July and unilaterally discontinued its in-store location program after notifying shoppers they were being tracked.

Fourth, it matters not whether a company is actually in the business of commercializing GPS data. In December, the FTC settled with the makers of an Android flashlight app after the agency claimed the company’s privacy policy was deceiving users into sharing their location and personal information with third-party advertisers. So there is still legal exposure for location information collection even if a firm operates in a completely different space.

Legal maneuvering can, at least for now, offset some of these risks. Under the current rules governing consumer class actions, several courts have decreed that privacy injury is insufficiently direct and substantial economically to support standing or to qualify for class action certification in federal court. For instance, in a case challenging a mobile app’s collection of geo-location data without consent, Goodman v. HTC America, Inc., the Western District of Washington held that the putative class members had not sufficiently plead injury to have standing. The court accepted as cognizable injuries overpayment for phones (because the plaintiffs would have paid less if they knew their location was to be collected as alleged) and diminution in value of the phones because of reduced battery life caused by the collection of geo-location data. Still, the court concluded that the “assertion that defendants misappropriated their personal information is not a sufficiently particularized injury to support [plaintiffs’] standing.” Yet since this opinion, and others from similar cases, holds out the possibility that identity theft or other financial harm may in the future result from insecure information collection, the standing defense appears to be time-limited.

The 4th Amendment protects people only from overreaching by the government. That may have led some in the business community to conclude prematurely that GPS and location tracking are issues only of concern to hackers and criminal enterprises. As these four developments show, however, location privacy is a serious business issue too.

Note: Originally written for and reposted with permission of my law firm’s Information Intersection blog.

Thirteen months after the U.S. Federal Trade Commission settled its antitrust investigation of Google Inc. by flatly declining to regulate the company’s search practices, the European Union is poised to do just that. This development highlights a serious rift between the two most influential competition authorities worldwide — and their very different value systems.

It has been true for years that on important Internet policy issues such as privacy, defamation, censorship and government surveillance, the 30-member EU has adopted principles far more intrusive for businesses, and likewise more protective of consumers, than in the U.S. Similarly, ever since a proposed General Electric-Honeywell merger was scuttled by the European Commission’s competition directorate in 2000, there have been a few highly visible cases in which the EU’s view of antitrust as a basis for protection of smaller entities in the marketplace has produced sharply different results.

So it is hardly surprising that EU Competition Commissioner Joaquin Almunia announced recently that several expanded concessions offered by Google to resolve his concerns about the fairness of the company’s search practices — which would fundamentally alter search by requiring Google to display links to rival search competitors on results pages served to its own search users — had finally borne fruit. The most basic competition issue asserted by the European authorities was that Google gives preference to its own services, like travel search, by placing those “specialised” (in European spelling) results above “organic” or natural search results. Google proposes to label these specialized results as paid placements and to add prominent links to rivals alongside. Despite vocal complaints by Google’s so-called vertical competitors that these substantial changes in search display — putting Expedia travel link results, for instance, on the same level of visibility as Google’s own sponsored links — still do not meet their needs, the fact that the EU is using its power to force serious search engine revisions on Google represents a watershed moment illustrating how far apart the two systems were and can still be at times.

There are three principal ways in which the inconsistent U.S. and EU Google settlements epitomize this continuing war of the worlds over antitrust enforcement:

- Is Google a Bottleneck “Gateway”? Almunia’s investigation was overtly premised on the concept that Google’s 90 percent share of Web searches in Europe (compared to some 70 percent in the U.S.), equals monopoly power as a gateway essential to success for Internet businesses. American jurisprudence, in contrast, has largely abandoned the bottleneck classification and its corollary, the “essential facilities” doctrine. Moreover, U.S. competition enforcers and courts distinguish between consumer preferences (which are changeable) and a dominant’s firm’s economic power (which can persist for long only when sheltered by entry barriers) in a way that contradicts the EU premise. As one federal court explained in January, the “ability to act as a ‘gatekeeper’ distinguishes broadband providers from other participants in the Internet marketplace — including prominent and potentially powerful edge providers such as Google and Apple — who have no similar control over access to the Internet for their subscribers and for anyone wishing to reach those subscribers.”

- Is Consumer Deception an Antitrust Issue? The EU has been focused, in large part, on the fact that when redesigning its search result displays, Google may have confused Internet users by not specifically indicating that some results are now based not on generic search algorithms, but instead a decision to integrate links to Google’s own services on results pages. Almunia believes that the potential for misleading consumers justifies a competition remedy, saying that Google must “signal what are the relevant options, alternative options, in the way they present the results.” In contrast, American antitrust law is clear that fraud, deceptive advertising and other commercial bad acts alone are not of competitive concern. Consumer protection remains important in the U.S., but our legal principles separate regulation of consumer issues from the competition-preservation function of antitrust policy.

- Should Antitrust Protect Traffic to Google’s Competitors? By far the biggest difference in the EU approach to competition enforcement is the historical European preference for domestic firms in established industries. In France, for instance, Internet publishers pay a tax that subsidizes newspapers and printed mapmakers, something anathema to the American idea of a free market. Where Google is concerned, the question becomes whether, as an important source of Web traffic for competing specialized search services, its practices should be regulated in order to guarantee hits to rival sites. The EU has been somewhat schizophrenic, at first condemning what it termed “diversion of traffic” to Google itself and characterizing its mission as to “guarantee that search results have the highest possible quality,” then later stressing that its “aim is not to artificially send traffic to sites that compete with Google.” The bottom line, however, is that by seeking to stop Google from “diverting” Internet search users from the complaining sites, the EU is in part attempting to dictate the results of competition, something American antitrust leaves to the marketplace.

Yes, these differences can sometimes be overstated. Both the EU and American antitrust agencies mutually believe that competitive markets produce the best outcomes and that, absent abuse by firms with monopoly power, the government should not try to pick winners and losers. The contrasting values typically appear only in hard cases, where the facts are ambiguous or the competitive consequences difficult to predict. Different enforcement decisions in Europe and the U.S. are uncommon, but when they do occur, are important as more than isolated instances.

There is a ray of light in all of this, one conclusion on which both Almunia and Jon Leibowitz, the former FTC Chairman who closed the U.S. government’s investigation of Google last year, agree wholeheartedly. Neither the EU nor the FTC accepts the premise of complaining search competitors that antitrust law embraces a concept they term “search neutrality,” namely that search providers must treat all queries and results under the same objective standard. The FTC said it had neither the desire nor institutional expertise to “regulate the intricacies of Google’s search engine algorithm.” The EU likewise concluded that its Google remedies should address “the way they present their own services” rather than “discussing the algorithm” used for Internet search.

This is one way, unlike the Martian invaders in the H.G. Wells novel, that the shared histories of America and Europe give the developed world a sustainable advantage in economic performance. On both the continent and in the New World, new business ideas succeed if they are better designed to meet the needs of consumers. With rare exceptions, we do not intervene in the marketplace to achieve government-desired competition results or to exclude some firms for political or social reasons. That is particularly key to the different Google search remedy approaches. Since everyone admits Google got to its present position by building a better search engine, the consequences of allowing competition policy to morph into an artificial tool of technology regulation by way of search neutrality are enforcement quicksand for the government, regardless of which “side of the pond” it sits.

When is a prediction not worth relying upon? For purposes of analyzing mergers under the Clayton Antitrust Act, a recent decision in favor of the Justice Department indicates that predictions are worth less — perhaps are even worthless — when they are contradicted by the actual facts of the marketplace. The government’s successful legal challenge a couple of weeks ago to the merger of two Internet start-ups ironically shows that the force of predictive judgments remains powerful, even when courts could employ reality as a basis for accurate comparison.

Some background. A 2013 DisCo post authored by the undersigned contrasted “future markets,” where the contours of products and entry do not yet exist and cannot reliably be predicted, with “nascent markets,” in which those features indeed exist but only in their infancy. My thesis was that antitrust enforcement in the latter is preferable because looking back at nascent markets once they have a chance to develop gives the government a more accurate basis on which to assess the actual impact of mergers and concentration than rank projections in which policymakers have no comparative expertise.

The case used to illustrate this theme was United States v. Bazaarvoice, Inc., in which the Justice Department sued to unwind a 2012 merger, already completed, between two firms in what it called the online ratings and reviews platform market. I concluded that

by challenging the merger post-consummation, DOJ has avoided basing its enforcement decisions on predictions of future markets and instead the case should rise or fall on the accuracy of its ex post analysis of actual competitive effects.

That’s not at all what happened, though.

Continue reading Is Bazaarvoice Bizarre?

Every new year sees a slew of top 5 and top 10 lists looking backwards. Here’s one that looks forward, predicting the five biggest disruptive technologies and threatened industries for 2014.

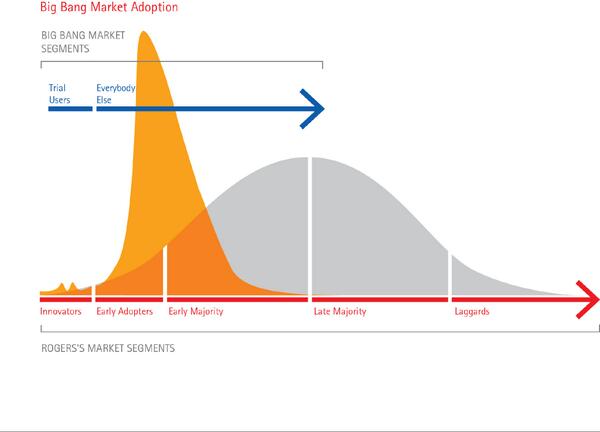

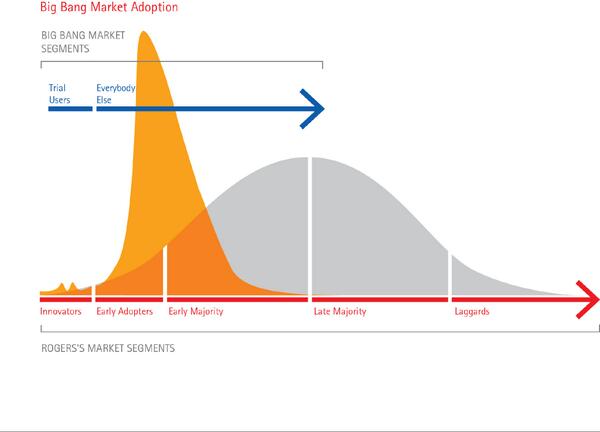

Making projections like these is really hard. Brilliant pundit Larry Downes titles his new book (co-authored with Paul Nunes) Big Bang Disruption: Strategy In an Age of Devastating Innovation. Its thesis is that with the advent of digital technology, entire product lines — indeed whole markets — can be rapidly obliterated as customers defect en masse and flock to a product that is better, cheaper, quicker, smaller, more personalized and convenient all at once.

Since adoption is increasingly all-at-once or never, saturation is reached much sooner in the life of a successful new product. So even those who launch these “Big Bang Disruptors” — new products and services that enter the market better and cheaper than established products seemingly overnight — need to prepare to scale down just as quickly as they scaled up, ready with their next disruptor (or to exit the market and take their assets to another industry).

Disruptors can come out of nowhere and happen so quickly and on such a large scale that it is hard to predict or defend against. “Sustainable advantage” is a concept alien to today’s technology markets. The reputation of the enterprise, aggregated customer bases, low-cost supply chains, access to capital and the like — all things that once gave an edge to incumbents — largely no longer exist or are equally available to far smaller upstarts. That’s extremely unsettling for business leaders because their function is no longer managing the present but inventing the future…all the time.

I certainly have no crystal ball. Yet just as makers of stand-alone vehicle GPS navigation devices were overwhelmed in 2013, suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere, by smartphone maps-app software, e.g., Google Maps, etc., so too do these iconic industries and services face a very real and immediate threat of big bang disruption this year.

Continue reading 5 Industries Facing Disruption In 2014

Despite the failures in recent years of such well-known retail chains as Circuit City, Borders and the like, it is way too soon to declare that the Internet will replace brick-and-mortar retailing. In part that is because consumer research suggests that in some segments, such as clothing, feeling and touching merchandise is an important part of the buying experience. Of interest to students of technological disruption, retailers are beginning in earnest to deploy technologies marrying the best aspects of online retailing with shopping malls and physical stores.

Delivery is one area where online retailers remain at a disadvantage. Amazon counters with its Prime membership for free two-day delivery, Amazon Lockers for local pick-up and its experimental foray into drone deliveries. Startups like Deliv (described as “a crowdsourced same-day delivery service for large national multichannel retailers”) are now providing equivalently fast store or home delivery for both online and in-person purchases.

Four of the nation’s largest mall operators are turning their properties into mini-distribution centers for rapid delivery, meaning shoppers can ditch their bags and keep spending. The service promises set delivery times for purchases consumers make at the mall or online from mall tenants, facilitated by a Silicon Valley start-up, Deliv Inc….The move highlights how delivery has become a key battleground in the war between physical and online retailers.

Startup Offers Same-Day Delivery at Shopping Malls | WSJ.com.

That in itself is remarkable. It shows that disruption is not a one-way street for legacy retailers. Yes, theirs is a challenging business environment, but technology is beginning to supply features for physical stores that meet and in some cases can beat online shopping providers. Home Depot, for instance, offers a smartphone app that allows consumers to check store inventory and aisle location, scan QR and UPC codes to get more information about products and order online with in-store delivery, overcoming some of the chain’s long-standing weaknesses: confusing layouts, out-of-stock merchandise and resulting abandoned visits.

Perhaps the most controversial realm is that of in-store consumer tracking and special offer distribution. This made news just last week when Apple Inc. turned on its iOS7 “iBeacon” service at its own retail stores. Macy’s has activated a shopkick-powered service through which simply walking into a Macy’s location will automatically send specialized offers to customers depending on where they are in the store. As Wired observed:

That’s just the beginning, though. Retailers are already talking about things like in-store navigation and dynamic pricing, all made possible by beacon-enhanced retail locations. For independent shops, iBeacon is a chance to jump into the smartphone era with one fell swoop. A $100 beacon is all it takes for even the mustiest book store to track customers, make recommendations, and offer discounts to customers’ pockets.

The risk, however, is that consumers may reject secret tracking technologies that retailers use internally, absent notice and consent. Over the last two years, retailers such as Nordstrom have hired software firms that gather Wi-Fi and Bluetooth signals emitted from smartphones to monitor shoppers’ movements around stores. They use the data to study things like wait times at the check-out line and how many people who browse actually make a purchase. At the prompting of Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) and the Washington, DC-based advocacy group Future of Privacy Forum, several location-tracking firms agreed in October to a code of conduct under which they will ask retailers to post signs in “conspicuous” spots in stores which inform consumers that their movements are being monitored and direct them to a website where they can opt-out. As Kashmir Hill noted in Forbes:

As with many novel and unexpected uses of technology, people have tended to be creeped out by the practice when they learn about it. Ask Path, which was tracking shoppers in malls (in 2011). Or Nordstrom, which came under fire earlier this year for tracking its shoppers without clear notice. Or London, which was using trash bins to collect info from passerbys’ mobile devices.

The flip side is that by offering recommendations and deals with an opt-in policy, retailers could dramatically bridge the divide between the online and brick-and-mortar experiences, making the latter still more like the former. Few consumers react negatively to Amazon or Netflix offering recommended products based on their past purchases. By doing the same thing in real-time, when a shopper passes the relevant store aisle or section, physical retailers would be in a position to offer something no e-commerce site can match: customized shopping with the ability to see, feel and take home impulse purchases enabled by technology.

There remain a slew of legal questions about whether the data collected by location-technology providers and retailers qualifies as personally identifiable data subject to the European Union Privacy Directive and the corresponding EU Safe Harbor in the U.S. In this country, it seems likely that the unique phone IDs associated with wireless devices — which are only linked to subscribers in the carrier’s switching and billing systems — would not be considered personal data by the Federal Trade Commission. In Europe, countries like the Netherlands and France have already articulated a more expansive view which could encompass device information in addition to name, address, phone numbers and the like. But even in the more liberal America, some have questioned whether retailers will be forced, whether by consumers or regulators, to dial-back autonomous tracking and adopt more transparent location practices.

All of this brings back memories for me personally. Nearly 15 years ago, I represented a start-up that was developing GPS chips for smartphones. While they are now ubiquitous (the start-up was sold to Qualcomm in March 2000), the challenges in making GPS work without a dedicated, external antenna were substantial. So like any good disruptor, my client went to the Federal Communications Commission to advocate cell phone location rules for E911 service that could give it a competitive advantage in the marketplace. The anecdote we used in our lobbying was that McDonald’s could message your phone, when passing one of its outlets, asking “Have you had your break today?” (That certainly dates the message, of course).

Technology has evolved so much that shopping is now almost at that place. Location tracking platform providers and their retail clients are offering a degree of interactivity never before available at retail. Whether it is compelling or creepy to consumers, of course, remains to be determined.

Note: The author has represented shopkick Inc., but not in connection with the company’s privacy policies and practices. Originally prepared for and reposted with permission of the Disruptive Competition Project.

I’ve spent a fair amount of time at Project DisCo discussing how political, legal and regulatory processes in the United States are largely biased against disruptive innovators in favor of legacy incumbents. That’s typically just as true for Uber and its ride-hailing competitors as it is for Aereo, Hulu, Netflix and other streaming video — or over the top (“OTT”) — Internet television services. But perhaps no longer.

The Consumer Choice in Online Video Act (S.1680), introduced by Sen. Jay Rockefeller, chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee, aims to change things. The legislation’s stated objectives are to “give online video companies baseline protections so they can more effectively compete in order to bring lower prices and more choice to consumers eager for new video options” and to “prevent the anticompetitive practices that hamper the growth of online video distributors.” It does so by (a) requiring television content owners to negotiate Internet carriage arrangements with OTT providers in good faith, (b) guaranteeing such firms reasonable access to video programming by limiting the use of contractual provisions that harm the growth of online video competition, and (c) empowering the FCC to craft regulations governing the program access interface between online providers and traditional television networks and studios.

S.1680 is a remarkable legislative effort to predict where the nascent online programming market is headed. It anticipates that in order to fulfill their competitive potential, OTT video entrants will require similar legal protections to what satellite television providers have for years enjoyed. The bill applies the program access model developed several decades ago for satellite television to the new world of OTT video.

As Rockefeller explained:

[He] has watched as the Internet has revolutionized many aspects of American life, from the economy, to health care, to education. It has proven to be a disruptive and transformative technology, and it has forever changed the way Americans live their lives. Consumers now use the Internet, for example, to purchase airline tickets, to reserve rental cars and hotel rooms, to do their holiday shopping. The Internet gives consumers the ability to identify prices and choices and offers an endless supply of competitive offerings that strive to meet individual consumer’s needs.

But that type of choice — with full transparency and real competition — has not been fully realized in today’s video marketplace. Rockefeller’s bill addresses this problem by promoting that transparency and choice. It addresses the core policy question of how to nurture new technologies and services, and make sure incumbents cannot simply perpetuate the status quo of ever-increasing bills and limited choice through exercise of their market power.

Modeled explicitly on the controversial 1992 Cable Act (which itself passed only over a presidential veto), S.1680 appears to be the first piece of legislation embracing disruption as a procompetiitive form of market evolution, including as its initial congressional “finding” that OTT services have the potential to “disrupt the traditional multichannel video distribution marketplace.” That’s excellent. At the same time, the bill’s choice of solution is contentious, by subjecting vertically integrated cable and television providers (e.g., Comcast-NBCu) to another regime of program access and retransmission mandates. The legal standard fashioned for testing the validity of a television distribution contract in S.1680 is whether it “substantially deters the development of an online video distribution alternative.” Given the highly visible retransmission disputes that have arisen in recent months, such as the Tennis Channel and CBS, plus the lack of evidence that vertical integration in fact provides an incentive for exclusive dealing and content foreclosure, free market advocates are likely to object to this. Proponents of net neutrality rules, especially where data caps are concerned, have already spoken out in support.

Continue reading OTT Disruption: Is the “Rockefeller Bill” the Answer?

No one in government or business has a crystal ball. Yet predictions of what is coming in markets characterized by rapid and disruptive innovation seem to be being made more often by competition enforcement agencies these days than in the past. It’s a trend that raises troublesome issues about the role of antitrust law and policy in shaping the future of competition.

Take two examples. The first is Nielsen’s $1.3 billion merger with Arbitron this fall. Nielsen specializes in television ratings, less well-known Arbitron principally in radio and “second screen” TV. Nonetheless, the Federal Trade Commission — by a divided 2-1 vote — concluded that if consummated, the acquisition might lessen competition in the market for “national syndicated cross-platform measurement services.” The consent decree settlement dictates that the post-merger firm sell and license, for at least eight years, certain Arbitron assets used to develop cross-platform audience measurement services to an FTC-approved buyer and take steps designed to ensure the success of the acquirer as a viable competitor.

In announcing the decree, FTC chair Edith Ramirez noted that “Effective merger enforcement requires that we look carefully at likely competitive effects that may be just around the corner.” That’s right, and the underlying antitrust law (Section 7 of the Clayton Act) has properly been described as an “incipiency” statute designed to nip monopolies and anticompetitive market structure in the bud before they can ripen into reality. Nonetheless, the difference is that making a predictive judgment about future competition in an existing market is different from predicting that in the future new markets will emerge. No one actually offers the advertising Nirvana of cross-platform audience measurement today. Nor is it clear that the future of measurement services will rely at all on legacy technologies (such as Nielsen’s viewer logs) in charting audiences for radically different content like streaming “over the top” television programming.

The problem is that divining the future of competition even in extant but emerging markets (“nascent” markets) is extraordinarily uncertain and difficult. That’s why successful entrepreneurs and venture capitalists make the big bucks, for seeing the future in a way others do not. That sort of vision is not something in which policy makers and courts have any comparative expertise, however. Where the analysis is ex post, things are different. In the Microsoft monopolization cases, for instance, the question was not predicting whether Netscape and its then-revolutionary Web browser would offer a cross-platform programming functionality to threaten the Windows desktop monopoly — it already had — but rather whether Microsoft abused its power to eliminate such cross-platform competition because of the potential long-term threat it posed. By contrast, in the Nielsen-Arbitron deal, the government is operating in the ex ante world in which the market it is concerned about, as well as the firms in and future entrants into that market, have yet to be seen at all.

This qualitative difference between nascent markets and future markets (not futures markets, which hedge the future value of existing products based on supply, demand and time value of money) is important for the Schumpterian process of creative destruction. When businesses are looking to remain relevant as technology and usage changes, they are betting with their own money. The right projection will yield a higher return on investment than bad predictions. Creating new products and services to meet unsatisfied demand may represent an inflection point, “tipping” the new market to the first mover, but it may also represent the 21st century’s Edsel or New Coke, i.e., a market that either never materializes or that develops very differently from what was at first imagined.

Continue reading Future Markets, Nascent Markets and Competitive Predictions

|

|

Three years later,

Three years later,